Curly Coat / Rough Coat Syndrome

and the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel

-

What It Is

What It Is - Symptoms

- DNA Testing

- Treatment

- Breeders' Responsibilities

- What You Can Do

- Research News

- Related Links

- Veterinary Resources

What It Is

Curly coat syndrome is a severe congenital condition of the skin, coat, claws, and eyes in some cavalier King Charles spaniel puppies. It is also known as rough coat syndrome and its scientific name is ichthyosis keratoconjunctivitis sicca. (Photo above at right is of a 10 week old cavalier with curly-coat syndrome, courtesy of Dr. K. C. Barnett.)

* It also is known as congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and as ichthyosiform dermatosis (CKCSID) and as autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis (ARCI).

In a May 2012 study of the DNA of 2,803 cavaliers, less than 0.15% were affected with the mutated gene causing curly coat syndrome, but over 8% of cavaliers were found to carry the defective gene. In a June 2012 report of DNA testing of 280 cavaliers, the UK's Animal Health Trust researchers estimate that 10.8% of CKCSs are carriers of curly-coat, and 0.4% are affected. It includes a very severe form of dry eye syndrome, but it is to be distinguished from the much more common form of dry eye in the CKSC breed.

No cases of curly coat syndrome with severe dry eye have been reported in any other breed. Studies have been conducted in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Sweden, the Czech Republic, and Iceland. During a two year period recently in Iceland, more than half of many litters of cavalier puppies were born affected by the syndrome. The disorder may be more widespread than previously believed as more owners and veterinarians become aware of its symptoms.

It has been determined to be due to a autosomal recessive gene, a mutation of the FAM83H gene*. As a result, affected puppies are more likely to be found in cases of line breeding or inbreeding on carrier bloodlines.

*This was confirmed most recently in a 2011 report and a 2012 report.

RETURN TO TOP

Symptoms

The reference to a curly or rough coat

comes from the unusually curly abnormality of the cavalier's coat which

is apparent at birth. (See photo of cavalier pup with curly coat syndrome

at

left.) However, the puppy also suffers from an extreme

version of dry eye*, and as the affected dog matures, it develops a

deterioration of the skin which results in seborrhea, consisting of skin

inflammation and excessive oiliness. Also, the dog's teeth, gums, and

other connective tissues may be adversely affected. The form of dry eye

associated with curly coat also is distinctive in that it is of congenital

origin.

is apparent at birth. (See photo of cavalier pup with curly coat syndrome

at

left.) However, the puppy also suffers from an extreme

version of dry eye*, and as the affected dog matures, it develops a

deterioration of the skin which results in seborrhea, consisting of skin

inflammation and excessive oiliness. Also, the dog's teeth, gums, and

other connective tissues may be adversely affected. The form of dry eye

associated with curly coat also is distinctive in that it is of congenital

origin.

*Dry eye is a syndrome very common in cavaliers. Read about it here.

In a

September 2012 article

by UK researchers who have studied this disorder for many years, they

describe

the symptoms thusly:

the symptoms thusly:

"Cases presented with a congenitally abnormal (rough/curly) coat and signs of KCS [keratoconjunctivitis sicca] from eyelid opening. Persistent scale along the dorsal spine and flanks with a harsh frizzy and alopecic coat was evident in the first few months of life. Ventral abdominal skin was hyperpigmented and hyperkeratinized in adulthood. Footpads were hyperkeratinized from young adulthood with nail growth abnormalities and intermittent sloughing."

Other signs include abnormal thickening of the outer layer of the footpads called hyperkeratosis, and abnormal claw formation, called symmetrical lupoid onychodystrophy (SLO). (Photo at right below shows hyperkeratosis of a footpad in a 6 month old CKCS.)

Adult cavaliers with the disorder typically have a "prematurely geriatic appearance with a crimped sparse coat", according to the same September 2012 article. (See the image of an 8-year-old affected Blenheim, at right.)

RETURN TO TOP

DNA Testing

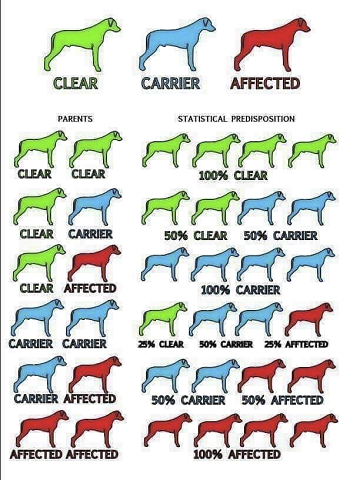

In 2011, two UK research groups (see below) independently developed DNA swab

tests for detecting a recessive gene, the FAM83H

gene, which, when mutated, is the cause of curly coat syndrome in the

CKCS. Curly coat/dry eye syndrome has been considered to be inherited as a autosomal recessive trait. If a DNA-tested cavalier is found to not have the mutated

FAM83H

gene, then it is "clear" of curly coat. If the dog is found to have two of the mutated

gene, then it is "affected" and has curly coat. If

the dog is found to have only one of the mutated gene, then it has been believed

to not be affected

but is "a carrier".

In 2011, two UK research groups (see below) independently developed DNA swab

tests for detecting a recessive gene, the FAM83H

gene, which, when mutated, is the cause of curly coat syndrome in the

CKCS. Curly coat/dry eye syndrome has been considered to be inherited as a autosomal recessive trait. If a DNA-tested cavalier is found to not have the mutated

FAM83H

gene, then it is "clear" of curly coat. If the dog is found to have two of the mutated

gene, then it is "affected" and has curly coat. If

the dog is found to have only one of the mutated gene, then it has been believed

to not be affected

but is "a carrier".

However, there is some evidence that cavaliers with only one of the

mutated FAM83H genes can display symptoms of curly coat and dry

eye.

In a

March 2020 article, a team of Australian researchers reported on a neutered male cavalier

first presented at age 15 months and subsequently

diagnosed with congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform

dermatosis (CKCSID). The dog has been found to have only a single copy

of the defective FAM83H gene and

was therefore considered to be heterozygous for this genetic defect and presumably only a

carrier. The dog's clinical signs have included progressively

severe dry eye for which no treatment has been successful. Initially,

the condition of the dog's coat has been relatively mild, perhaps

reflecting the dog's heterozygous state. No daily treatment has cured

any of the dog's conditions, but it has offered some control and relief.

The researchers concluded:

In a

March 2020 article, a team of Australian researchers reported on a neutered male cavalier

first presented at age 15 months and subsequently

diagnosed with congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform

dermatosis (CKCSID). The dog has been found to have only a single copy

of the defective FAM83H gene and

was therefore considered to be heterozygous for this genetic defect and presumably only a

carrier. The dog's clinical signs have included progressively

severe dry eye for which no treatment has been successful. Initially,

the condition of the dog's coat has been relatively mild, perhaps

reflecting the dog's heterozygous state. No daily treatment has cured

any of the dog's conditions, but it has offered some control and relief.

The researchers concluded:

"Of particular significance in the present case was the fact that the dog had only one copy of the abnormal gene and hence, assuming an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, should not have displayed clinical signs. This raises the possibility, as was previously suggested,2 that the mode of inheritance may not be a simple autosomal recessive, but may involve partial or incomplete penetrance, modifying genes or it may be a multi-gene lesion."

The knowledge of whether a cavalier is clear, affected, or a carrier of curly coat is important to the responsible breeder who wants to avoid passing curly coat to future generations in her bloodline of cavaliers. See Breeders' Responsibilities below for additional information about how to use the results of DNA testing to choose breeding partners.

Genetic testing laboratories which test for this mutation causing Curly Coat Syndrome include:

• American Kennel Club (AKC)

• Canine Genetic Testing (CAGT), University of Cambridge Dept. of Veterinary Medicine

• Embark, Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine

• GenSol Animal Diagnostics

• Laboklin

• Orivet

• Paw Print Genetics

![]() Watch

this YouTube video to learn how to properly use a swab to obtain DNA from

your dog. See our Genetic Testing webpage for

more information about DNA testing.

Watch

this YouTube video to learn how to properly use a swab to obtain DNA from

your dog. See our Genetic Testing webpage for

more information about DNA testing.

The Animal Health Trust (AHT) reported that, as of May 15, 2012: 2,803 cavaliers had been DNA-tested for curly coat syndrome, of which 4 (0.1427%) were "affected" with two of the mutated curly coat gene; 225 (8.027%) were "carriers" with only one of the mutated gene; and the rest, 2,574 (91.830%), were clear of the defective gene. In a June 2012 report of DNA testing of 280 cavaliers, AHT researchers estimate that 10.8% of CKCSs are carriers of curly-coat, and 0.4% are affected.

RETURN TO TOP

Treatment

In cases of curly coat syndrome, nearly continuous daily

care, including very frequent medicinal bathing, is required to treat

the skin condition, as well as applying the eye medications.

In cases of curly coat syndrome, nearly continuous daily

care, including very frequent medicinal bathing, is required to treat

the skin condition, as well as applying the eye medications.

Early treatment of dry eye is crucial to preventing destruction of the CKCS's cornea. Treatment is aimed at increasing tear production, applying artificial tears, and reducing any bacterial infections, and decreasing inflammation and scarring of the cornea. The dog's eyes must be kept clean and free of discharge. The patient may be treated initially with a topical antibiotic or anti-inflammatory.

Lacrimostimulant medications such as cyclosporin 1% and 2%, cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion (Restasis) or ointment (Optimmune) and tacrolimus ophthalmic suspension are commonly prescribed daily for life to increase tear production, and artificial tear solutions, in liquid or ointment format, must be applied frequently each day to eliminate bacteria, rinse the eyes, and remove discharge.

NOTE: In a 2008 study of 25 dogs, including a cavalier, researchers observed that "brachycephalic dogs with a background of chronic keratitis that are treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [including cyclosporine] are at risk to develop axial corneal SCC [squamous cell carcinoma]. The increase in annual cases of SCC suggests that this phenomenon is a developing problem." See also a 2011 study which concluded, "Chronic inflammatory conditions of the cornea and topical immunosuppressive therapy may be risk factors for developing primary corneal SCC in dogs."

In a 2003 study reported by Dr. Keith C. Barnett, European specialist in veterinary ophthalmology, the dry eye condition of curly coat dogs may be so severe that cyclosporine therapy is ineffective, and the skin condition progresses into severe lesions. In a September 2006 paper, Dr. Barnett reported that successful treatment of the skin condition is not possible, although there can be some improvement in the dry eye condition.

In a 2011 research study, Dr. Barnett and others found that "lacrimostimulant treatment [e.g., cyclosporin] had no statistically significant effect on Schirmer tear test results, although subjectively, this treatment reduced progression of the keratitis [dry eye]."

Dr. Barnett also reported in his 2003 study that the need for constant care of the eyes and skin may lead breeders to resort to early euthanasia of the affected puppies as the only humane result, to avoid the dogs suffering from lifetimes of extreme discomfort and permanent eye damage.

In a 2013 study, Dr. David L. Williams reports developing a gel which does not require as many doses per day as do the liquid medications. The gel is a crosslinked hydrogel based upon a modified, thiolated hyaluronic acid (HA), which he has labelled xCMHA-S. He stated:

"Further, in a preliminary clinical study of dogs with KCS [including 3 CKCSs], the gel significantly reduced the symptoms associated with KCS within two weeks while only being applied twice daily. The reduction of symptoms combined with the low dosing regimen indicates that this gel may lead to both improved patient health and owner compliance in applying the treatment."

In a March 2020 article, a team of Australian researchers reported on a neutered male cavalier first presented at age 15 months and subsequently diagnosed with congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis (CKCSID). The dermatosis and the keratoconjunctivitis were being managed by ongoing symptomatic therapy, with reasonable response to the former, however, the keratoconjunctivitis sicca was expected to result in eventual blindness. Treatment with oclacitinib maleate (16 mg BID; Apoquel) was instigated to control the pruritus associated with the ichthyosis, which was double the usual maintenance dose, but lowering the dose resulted in the return of the pruritus and scratching. The owners reported that this treatment was more effective than the prednisolone had been. The owners also cleansed the dog's ears and paws twice daily, using Otoflush and Malaseb shampoo (Dermcare) and reported that this was helpful in controlling pruritus. Nevertheless, otitis externa that required medical treatment still tended to occur 3-4 times a year. Fifteen months after the histopathological confirmation of the CKCSID diagnosis, the eyes had deteriorated further; corneal vascularisation and opacity had developed. A veterinary ophthalmologist reported it was difficult to see the anterior chamber, iris, lens and vitreous. ... The prognosis therefore remained poor with ongoing vision loss likely.

Surgery rarely is a successful option. In severe cases that do not respond to medications, an expensive surgical procedure may be performed in which a salivary duct is moved from the mouth to the eye. This results in saliva flowing over the eye to keep the eye moist. It is not an ideal treatment for dry eye, because saliva is not the same as tears, and the flow of saliva cannot be as well controlled. The surgery is helpful, however, for those dogs that remain persistently painful and squinty despite trying all forms of medical therapy

RETURN TO TOP

Breeders' Responsibilities

Breeders

should have DNA tests performed on all cavalier breeding stock before matings,

to detect the mutations causing curly coat syndrome in the CKCS.

See our DNA Testing Section for more information

about the available DNA testing programs.

Breeders

should have DNA tests performed on all cavalier breeding stock before matings,

to detect the mutations causing curly coat syndrome in the CKCS.

See our DNA Testing Section for more information

about the available DNA testing programs.

-- breeding decisions using DNA results

• If two clear cavaliers are mated, all offspring likewise should be clear of curly coat.

• If a clear cavalier is mated to a carrier, the odds are that half of the puppies in the resulting litter will be clear and half will be carriers.

• If two carriers are mated, the odds are that half of the litter will be carriers, a quarter will be affected, and a quarter will be clear.

• If a carrier and an affected are mated, half of the litter should be affected and half should be carriers.

• If two affecteds are mated, all puppies in the litter should be affected.

Obviously, it would be preferable to mate only clear cavaliers to each other. But if a cavalier breeder finds that one of her breeding stock is a carrier, she should mate that dog only to a clear cavalier. Then, once the litter is produced, the breeder should DNA-test the puppies to identify the half that are clear and half that are carriers, and remove the carriers from the breeding program.*

* Read the UK Animal Health Trust's article on "Should We Breed Carriers?" by Dr. Cathryn Mellersh here.

Two carriers should not be mated to each other, and, of course, no affecteds should be mated at all.

If a breeder DNA-tests her breeding stock for the mutated gene causing curly coat and then follows the above breeding protocol, she could eliminate all curly coat-carriers from her bloodline within two generations.

As of February 2013, the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Club, USA recommends that its members/breeders comply with this breeding protocol.

The Genetics Committee of the ACVO recommends that CKCSs affected with curly coat not be bred. See The Blue Book.

RETURN TO TOP

What You Can Do

If you suspect your cavalier has this disorder, have the dog's DNA tested. See our DNA Testing Section for details.

RETURN TO TOP

Research News

August 2020: The Animal Health Trust discontinued its DNA testing services as of July 31, 2020. The former staff of the AHT's canine genetics research office, led by Dr. Cathryn Mellersh, are planning to to open a new DNA testing service. For more information about this, go to the Canine-Genetics website.

April 2020:

A cavalier with a single defective FAM83H gene is diagnosed with

curly coat/dry eye syndrome.

In a

March 2020 article, a team of Australian researchers (Judith S. Nimmo

[right],

E. McMillan, G. Sofronidis) report on a neutered male cavalier King

Charles spaniel first presented at age 15 months and subsequently

diagnosed with congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform

dermatosis (CKCSID). The dog has been found to have only a single copy

of the defective FAM83H gene found to be associated with CKCSID and

therefore heterozygous for this genetic defect and presumably only a

carrier. However, the dog's clinical signs have included progressively

severe dry eye for which no treatment has been successful. Initially,

the condition of the dog's coat has been relatively mild, perhaps

reflecting the dog's heterozygous state. No daily treatment has cured

any of the dog's conditions, but it has offered some control and relief.

The researchers concluded:

In a

March 2020 article, a team of Australian researchers (Judith S. Nimmo

[right],

E. McMillan, G. Sofronidis) report on a neutered male cavalier King

Charles spaniel first presented at age 15 months and subsequently

diagnosed with congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform

dermatosis (CKCSID). The dog has been found to have only a single copy

of the defective FAM83H gene found to be associated with CKCSID and

therefore heterozygous for this genetic defect and presumably only a

carrier. However, the dog's clinical signs have included progressively

severe dry eye for which no treatment has been successful. Initially,

the condition of the dog's coat has been relatively mild, perhaps

reflecting the dog's heterozygous state. No daily treatment has cured

any of the dog's conditions, but it has offered some control and relief.

The researchers concluded:

"Of particular significance in the present case was the fact that the dog had only one copy of the abnormal gene and hence, assuming an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, should not have displayed clinical signs. This raises the possibility, as was previously suggested,2 that the mode of inheritance may not be a simple autosomal recessive, but may involve partial or incomplete penetrance, modifying genes or it may be a multi-gene lesion."

August

2013:

Dr.

David L. Williams develops a gel for treating dry eye.

In a

2013 study, Dr. David L. Williams (right) of UK's Cambridge University, reports developing a gel which does not

require as many doses per day as due the liquid medications. The gel is

a crosslinked hydrogel based on a modified, thiolated hyaluronic acid

(HA), labelled "xCMHA-S". He stated:

In a

2013 study, Dr. David L. Williams (right) of UK's Cambridge University, reports developing a gel which does not

require as many doses per day as due the liquid medications. The gel is

a crosslinked hydrogel based on a modified, thiolated hyaluronic acid

(HA), labelled "xCMHA-S". He stated:

"Further, in a preliminary clinical study of dogs with KCS [including 3 CKCSs, the gel significantly reduced the symptoms associated with KCS within two weeks while only being applied twice daily. The reduction of symptoms combined with the low dosing regimen indicates that this gel may lead to both improved patient health and owner compliance in applying the treatment."

July

2013:

CKCSC,USA

adopts the curly coat syndrome DNA testing scheme as a recommended breeding

practice. At its February 21, 2013 board of directors meeting, the

Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Club, USA adopted the

DNA breeding protocol for curly

coat syndrome (and also for

episodic falling

syndrome), as a "recommended breeding practice."

July

2013:

CKCSC,USA

adopts the curly coat syndrome DNA testing scheme as a recommended breeding

practice. At its February 21, 2013 board of directors meeting, the

Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Club, USA adopted the

DNA breeding protocol for curly

coat syndrome (and also for

episodic falling

syndrome), as a "recommended breeding practice."

April 2013: UK's Kennel Club adopts the DNA testing scheme for curly coat syndrome in the CKCS. Finally, the UK Kennel Club has announced that it has approved the DNA testng scheme for curly coat syndrome (and also for episodic falling syndrome) in the cavalier breed. Details on the KC's website here.

March 2013: UK cavalier clubs urge Kennel Club to include Curly Coat DNA test in KC's registration system. The UK cavalier clubs' Cavalier Health Laison Committee voted to ask the UK Kennel Club to include all results from the Episodic Falling (EF) and Curly Coat (DE/CC) DNA tests in the KC's registration system and in its Health Test Results Finder. Furthermore the Clubs requested that all cavaliers be tested for both EF and DE/CC prior to breeding and that at least one parent of each litter is free of each mutation, to ensure no affected puppies can be produced or registered.

July 2012: VetGen joins the curly-coat DNA test team. Veterinary Genetic Services (VetGen), a US company located in Ann Arbor, Michigan, which provides canine genetic disease detection services, offers test kits for identifying the genetic defect causing curly coat in cavaliers. VetGen's website for ordering the test kit is here.

June

2012:

UK's Animal Health Trust estimates 10.8% of CKCSs are curly-coat

carriers. The Animal Health Trust has issued its report of its

examination of DNA of 280 UK Kennel Club cavalier King Charles spaniels. Based

upon the results of the study, AHT has estimated that 10.8% of the overall

population of UK cavaliers are carriers of curly coat syndrome and that 0.4% are

affected. The study also

included the CKCSs' episodic falling syndrome. AHT estimates that 19.1% of

cavaliers are carriers of EFS.

AHT estimates that 1% to 2% of cavaliers carry both EFS and curly-coat.

The entire report is available here.

May 2012: UK's Animal Health Trust reports interim results of DNA testing. The Animal Health Trust reported that, as of May 15, 2012: 2,803 cavaliers have been DNA-tested for curly coat syndrome, of which 4 (0.1427%) have been found to be "affected" with two of the mutated curly coat gene; 225 (8.027%) are "carriers" with only one of the mutated gene; and the rest, 2,574 (91.830%), are clear of the defective gene.

January 2012: UK researchers identify mutated gene causing curly coat in the cavalier. Drs. Oliver P. Forman, Jacques Penderis, Claudia Hartley, Louisa J. Hayward, Sally L. Ricketts, and Cathryn S. Mellersh of the Animal Health Trust and University of Glasgow have identified a mutation of the FAM83H gene was associated with curly coat in the CKCS. See report below.

December 2011: UK researchers find dry eye medications have mixed results. In a 2011 UK study of cavaliers suffering from both dry eye and curly coat syndrome, the researchers found that "lacrimostimulant treatment had no statistically significant effect on Schirmer tear test results, although subjectively, this treatment reduced progression of the keratitis [dry eye]."

April 2011: Animal Health Trust Starts DNA Test for Curly Coat in Cavaliers. On April 18, 2011. Animal Health Trust (AHT) begins offering to cavalier breeders its DNA test to detect the mutations causing dry eye/curly coat syndrome, through the AHT's online DNA testing webshop. The DNA test is available world-wide. Read more here.

November

2010: DNA Region for Curly Coat Has Been Found.

Animal Health Trust (AHT) veterinary geneticist Dr. Tom Lewis (right)

announced at the UK Cavalier Club's "Cavalier Health Day" on November 20 that

the DNA region for the curly coat syndrome in cavaliers has been located. The

AHT is continuing its research, started by the late Dr. Keith C. Barnett, to

identify the precise mutations of gene(s) causing curly coat syndrome (ichthyosis keratoconjunctivitis sicca).

The Trust's future plan is to offer a DNA test for the mutations to cavalier

breeders.

November

2010: DNA Region for Curly Coat Has Been Found.

Animal Health Trust (AHT) veterinary geneticist Dr. Tom Lewis (right)

announced at the UK Cavalier Club's "Cavalier Health Day" on November 20 that

the DNA region for the curly coat syndrome in cavaliers has been located. The

AHT is continuing its research, started by the late Dr. Keith C. Barnett, to

identify the precise mutations of gene(s) causing curly coat syndrome (ichthyosis keratoconjunctivitis sicca).

The Trust's future plan is to offer a DNA test for the mutations to cavalier

breeders.

March 2009: Dr. Keith C. Barnett died on March 10, 2009.

April

2007:

Drs. R. F.

Sanchez (right), G. Innocent, J.

Mould, and F. M. Billson

reported in an April 2007 report that the cavalier King Charles spaniels in their study

"showed a more acute disease pattern with a biphasic age distribution at 0 to

less than two years of age, and four to less than six and six to less than eight

years of age, respectively, with more males affected than females and a

significantly higher incidence of ulcerative keratitis in some cases resulting

in corneal perforation."

April

2007:

Drs. R. F.

Sanchez (right), G. Innocent, J.

Mould, and F. M. Billson

reported in an April 2007 report that the cavalier King Charles spaniels in their study

"showed a more acute disease pattern with a biphasic age distribution at 0 to

less than two years of age, and four to less than six and six to less than eight

years of age, respectively, with more males affected than females and a

significantly higher incidence of ulcerative keratitis in some cases resulting

in corneal perforation."

March

2007: Animal Health Trust researches CKCS inheritance pattern for curly

coat syndrome. The Animal Health Trust (AHT) is conducting research to try to establish the

pattern of

inheritance of CKCS puppies born with the combination of both dry eye

and curly coat syndrome (ichthyosis keratoconjunctivitis sicca), which appears

to be unique to the cavalier as a breed. According to Dr. Keith C.

Barnett (left), European specialist in

veterinary ophthalmology, who has been studying these conditions for several

years, no cases of the two abnormalities occurring together have been recorded

in any other breed.

inheritance of CKCS puppies born with the combination of both dry eye

and curly coat syndrome (ichthyosis keratoconjunctivitis sicca), which appears

to be unique to the cavalier as a breed. According to Dr. Keith C.

Barnett (left), European specialist in

veterinary ophthalmology, who has been studying these conditions for several

years, no cases of the two abnormalities occurring together have been recorded

in any other breed.

Dr. Barnett and Dr. Cathryn Mellersh, senior canine geneticist at the AHT, are leading a team of AHT colleagues who are researching the DNA of the puppies. Dr. Mellersh reports that twenty-seven candidate genes have been identified and the tests are currently in progress and final results are pending.

Dr. Barnett requests that breeders who have puppies affected with these combined disorders send blood samples and skin tissue samples from the affected puppies, their siblings, and parents to identify the responsible gene. Contact Dr. Barnett at the AHT if you wish to participate in the research project. He may be reached at Animal Health Trust, Lanwades Park, Kentford, Newmarket, CB8 7UU, United Kingdom; telephone: (+44) (0)8700 502424; email: Keith.Barnett@aht.org.uk Blood samples of 3 to 5 ml should be provided in ETDA anti-coagulant tubes. Alternatively, for very young or old donors, cheek swabs may be used. Samples should be marked for the attention of Dr. K. Barnett and sent to: Sarah Gray, The Animal Health Trust, Lanwades Park, Newmarket Suffolk CB8 7UU UK. Please indicate clearly that the samples are Curly Coat affected or related. Dr. Mellersh may be reached at Animal Health Trust, Lanwades Park, Kentford, Newmarket, Suffolk CB8 7UU, United Kingdom; telephone: (+44) (0)1638 750659 ; email: cathryn.mellersh@aht.org.uk

RETURN TO TOP

Related Links

RETURN TO TOP

Veterinary Resources

Congenital ichthyosis in two cavalier King Charles spaniel littermates. Z. Alhaidari, J,P. Ortonne. Vet.Dermatology. 1994;5:117-121. Quote: "Congenital ichthyosis in two Cavalier King Charles littermates is described. Clinical lesions in the more severely affected dog consisted of mild generalized scaling, thick brown verrucous scales on the abdomen, and hyperkeratosis of the footpad margins. Histology revealed an extreme orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and an irregular granular layer while electron microscopy demonstrated the division of the cytoplasm of the keratinocytes into three compartments and the persistence of the attachment of the tonofilaments to the desmosomes in the upper layers of the epidermis. Etretinate therapy could not be maintained due to adverse effects and topical therapy only was not very effective."

Dry eye and curly coat in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. Barnett, KC, Veterinary Ophthalmology 6 (4), 343-350, Dec. 2003.

Guide to Congenital and Heritable Disorders in Dogs. Dodds WJ, Hall S, Inks K, A.V.A.R., Jan 2004, Section II(179).

Breed Predispositions to Disease in Dogs & Cats. Alex Gough, Alison Thomas. 2004; Blackwell Publ. 44-45.

Ophthalmic Disease in Veterinary Medicine. Martin C.L. Manson Publ. 2005.

Congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis in the cavalier King Charles spaniel. K. C. Barnett. J.Sm.Anim.Prac. 2006 Sep;47(9):524-8. Quote: Objectives: To record a previously unreported congenital and hereditary condition affecting the eyes and skin in the cavalier King Charles spaniel. Methods: Nineteen cases (13 litters) were investigated, with particular reference to eye and skin clinical signs. In addition, five generation pedigrees were obtained and studied from all cases with the exception of one. Results: The eye signs were due to keratoconjunctivitis sicca, a common ocular disease in the dog, but rarely of congenital origin. The skin signs were of an ichthyosiform dermatosis; ichthyosis being a rare skin disease in the dog. In human beings, ichthyosis is a similar disease, mainly inherited and with a neonatal onset, and sometimes accompanied by other developmental defects. In the cavalier King Charles spaniel, the coat abnormality was noted at birth by the breeders as a 'curly coat', with deterioration of the skin signs as the animal became adult. Clinical Significance: These two conditions occurring together in this breed is well recognised by some breeders but rarely by the veterinary profession. Successful treatment is not possible, although some improvement, particularly of the keratoconjunctivitis sicca, can be obtained. The probable hereditary nature of the condition is an important factor for control.

Canine keratoconjunctivitis sicca: disease trends in a review of 229 cases. R. F Sanchez, G Innocent, J Mould, F. M Billson. J.Sm.Anim.Pract.; April 2007;48(4): 211-217. Quote: "There were 44 breeds in the study, with four breeds, English cocker spaniels, cavalier King Charles spaniels, West Highland white terriers and shih-tzus, making up 58 per cent of the cases. ... In contrast, cavalier King Charles spaniels and shih-tzus showed a more acute disease pattern with a biphasic age distribution at 0 to less than two years of age, and four to less than six and six to less than eight years of age, respectively, with more males affected than females and a significantly higher incidence of ulcerative keratitis in some cases resulting in corneal perforation. ... In the USA, predisposed breeds include cavalier King Charles spaniels (CKCS), English bulldogs, Lhasa apsos, shih-tzus, West Highland white terriers (WHWT), pugs, bloodhounds, American cocker spaniels, Pekingeses, Boston terriers, miniature schnauzers and Samoyeds (Kaswan and Salisbury 1990)."

Efficient mapping of mendelian traits in dogs through genome-wide association. Elinor K Karlsson, Izabella Baranowska, Claire M Wade1, Nicolette H C Salmon Hillbertz, Michael C Zody, Nathan Anderson, Tara M Biagi, Nick Patterson, Gerli Rosengren Pielberg, Edward J Kulbokas III, Kenine E Comstock, Evan T Keller, Jill P Mesirov, Henrik von Euler, Olle Kampe, Åke Hedhammar, Eric S Lander, Goran Andersson, Leif Andersson, Kerstin Lindblad-Toh. Nature Genetics. Sept. 2007;39:1321 - 1328. Quote: "With several hundred genetic diseases and an advantageous genome structure, dogs are ideal for mapping genes that cause disease. Here we report the development of a genotyping array with ~27,000 SNPs and show that genome-wide association mapping of mendelian traits in dog breeds can be achieved with only ~20 dogs. Specifically, we map two traits with mendelian inheritance: the major white spotting (S) locus and the hair ridge in Rhodesian ridgebacks. For both traits, we map the loci to discrete regions of <1 Mb. Fine-mapping of the S locus in two breeds refines the localization to a region of ~100 kb contained within the pigmentation-related gene MITF. Complete sequencing of the white and solid haplotypes identifies candidate regulatory mutations in the melanocyte-specific promoter of MITF. Our results show that genome-wide association mapping within dog breeds, followed by fine-mapping across multiple breeds, will be highly efficient and generally applicable to trait mapping, providing insights into canine and human health."

Immunopathogenesis of Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca in the Dog. David L. Williams. Vet Clin Small Anim 38 (2008) 251-268.

Corneal squamous cell carcinoma in dogs with a history of chronic keratitis. R. R. Dubielzig, C. S. Schobert and J. Dreyfus. Vet Ophth; 2008;11(6):413-429. Quote: "Purpose: Corneal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a rare tumor in dogs. The COPLOW has seen a recent increase in primary SCC in the axial cornea. We report here on 25 cases. Methods: Twenty-five cases of primary axial corneal SCC were selected from the COPLOW collection which includes more that 6000 neoplastic specimens. ... Results: The number of canine corneal SCC has risen in the past several years from 1 case per year from 1998 to 2004, jumping to 6 cases in 2005, 8 cases in 2006, and 7 cases in 2007. Brachycephalic breeds are overrepresented. The breed distribution included 8 Pugs, 5 Bulldog, 2 Boxers, 2 Greyhound, 2 Shi Tzu, 2 Border Collie, 2 Pekinese, 1 Bassett, 1 Chow, 1 Cocker, and 1 Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. No correlation to sex was found. Out of the 25 cases, 21 showed signs of chronic keratitis prior to developing SCC. In the remaining 4 cases the prior corneal history was unknown. Within the group of 25, 10 cases had been treated with cyclosporine alone, 4 with tacrolimus alone, 5 with both cyclosporine and tacrolimus, and 6 treated with other drugs or unknown. Follow-up information was obtained from 23 cases with a follow-up interval of between 5 days and 31 months (mean: 7.9 months). Three dogs had died for reasons unrelated to the ocular disease. One dog had recurrent disease extending deeply into the cornea. Conclusions: Brachycephalic dogs with a background of chronic keratitis that are treated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs are at risk to develop axial corneal SCC. The increase in annual cases of SCC suggests that this phenomenon is a developing problem."

Congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis (ckcsid) in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS) dog: a candidate gene study. C. Hartley, K. C. Barnett, C. S. Mellersh, L. Pettitt and O. P. Forman. Vet Ophthal (2009) 12(6):379-385. Quote: "Purpose: To identify causative mutation(s) for CKCSID in CKCS dogs using a candidate gene approach. Methods: DNA samples from 21 cases/parents were collected. Canine candidate genes (CCGs) for similar inherited human diseases were chosen. Twenty-eight candidate genes were identified by searching the Pubmed database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez/query.fcgi). Canine orthologs of human candidate genes were identified using the Ensembl orthologue prediction facility (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html). Two microsatellites flanking each candidate gene were selected and primers to amplify each microsatellite were designed using the Whitehead Institute primer design website (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgibin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi). The microsatellites associated with all 28 CCGs were genotyped on a panel of 21 DNA samples from CKCS dogs (13 affected, 8 carriers). Genotyping data was analysed to identify markers homozygous in affected dogs and heterozygous in carriers (homozygosity mapping). Results: None of the microsatellites associated with 25 of the CCGs displayed an association with CKCSID in the 21 DNA samples tested. Three CCGs associated microsatellites were monomorphic across all samples tested. Conclusion: Twenty five CCGs were excluded as cause of CKCSID. Three CCGs could not be excluded from involvement in the inheritance of CKCSID."

Breed Predispositions to Disease in Dogs & Cats (2d Ed.). Alex Gough, Alison Thomas. 2010; Blackwell Publ. 51, 54.

Congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis in 25 Cavalier King Charles spaniel dogs - part I: clinical signs, histopathology, and inheritance. Claudia Hartley, David Donaldson, Ken C. Smith, William Henley, Tom W. Lewis, Sarah Blott, Cathryn Mellersh, Keith C. Barnett. Vet.Opht. January 2011; doi:10.1111/j.1463-5224.2011.00986.x. Quote: The clinical presentation and progression (over 9 months to 13 years) of congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis (CKCSID) in the Cavalier King Charles spaniel dog are described for six new cases and six previously described cases. Cases presented with a congenitally abnormal (rough/curly) coat and signs of KCS from eyelid opening. Persistent scale along the dorsal spine and flanks with a harsh frizzy and alopecic coat was evident in the first few months of life. Ventral abdominal skin was hyperpigmented and hyperkeratinized in adulthood. Footpads were hyperkeratinized from young adulthood with nail growth abnormalities and intermittent sloughing. Long-term follow-up of cases (13/25) is described. Immuno-modulatory/lacrimostimulant treatment had no statistically significant effect on Schirmer tear test results, although subjectively, this treatment reduced progression of the keratitis. Histopathological analysis of samples (skin/footpads/ lacrimal glands/salivary glands) for three new cases was consistent with an ichthyosiform dermatosis, with no pathology of the salivary or lacrimal glands identified histologically. Pedigree analysis suggests the syndrome is inherited by an autosomal recessive mode.

Superficial corneal squamous cell carcinoma occurring in dogs with chronic keratitis. Jennifer Dreyfus, Charles S. Schobert, Richard R. Dubielzig. Vet Ophth; May 2011;14(3):161-168. Quote: "Objective: Canine corneal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a rare tumor, with only eight cases previously published in the veterinary literature. The Comparative Ocular Pathology Lab of Wisconsin (COPLOW) has diagnosed 26 spontaneously occurring cases, 23 in the past 4 years [three of which were cavalier King Charles spaniels]. This retrospective study describes age and breed prevalence, concurrent therapy, biologic behavior, tumor size and character, and 6-month survival rates after diagnosis. Results: A search of the COPLOW database identified 26 corneal SCC cases diagnosed from 1978 to 2008. There is a strong breed predilection (77%) in brachycephalic breeds, particularly those prone to keratoconjunctivitis sicca. The mean age was 9.6 years (range 6-14.5 years). Follow-up information >6 months was available for 15 of 26 cases. Recurrence occurred in the same eye in nine cases, seven of which were incompletely excised at the time of first keratectomy. No cases were known to have tumor growth in the contralateral eye and no cases of distant metastases are known. Where drug history is known, 16 of 21 dogs had a history of treatment with topical immunosuppressive therapy (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) at the time of diagnosis. Conclusion: Chronic inflammatory conditions of the cornea and topical immunosuppressive therapy may be risk factors for developing primary corneal SCC in dogs. SCC should be considered in any differential diagnosis of corneal proliferative lesions. Superficial keratectomy with complete excision is recommended, and the metastatic potential appears to be low."

Genetic Connection: A Guide to Health Problems in Purebred Dogs, Second Edition. Lowell Ackerman. July 2011; AAHA Press; pg 55. Quote: "A poorly characterized ichthyosiform dematosis with keratoconjunctivitis has been reported in the Cavalier King Charles spaniel as a congential condition that gets progressively worse with age. The keratinization disorder is reported at birth or shortly thereafter, often involving footpads, claws, and clawfolds; the keratoconjunctivitis sicca is also noted at a very young age. DNA testing is available."

New DNA tests for Cavalier King Charles spaniels. Vet Rec 2011 168(14):370. "NEW DNA tests to detect the mutations causing congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis (dry eye and curly coat syndrome) and episodic falling in Cavalier King Charles spaniels will be available from the Animal Health Trust (AHT) later this month. Episodic falling is a neurological condition induced by exercise, excitement or frustration. The dog's muscle tone increases and the animal is unable to relax its muscles, becomes rigid and falls over. Dry eye and curly coat syndrome results in an affected dog producing no tears, so its eyes become sore. The skin becomes flaky and dry, particularly around the feet, which can make standing and walking difficult and painful. The syndrome appears to be unique to Cavalier King Charles spaniels and most dogs diagnosed with it are euthanased. Researchers at the Kennel Club Genetics Centre at the AHT have now identified the mutations responsible for the two conditions. This has allowed the development of the new DNA tests, which will be available from the AHT from April 18. Cathryn Mellersh, head of canine genetics at the AHT, said: To date there has been no long-term effective treatment for either dry eye and curly coat syndrome or episodic falling so the development of the DNA tests is an important breakthrough for breeders and owners of Cavalier King Charles spaniels. As with all inherited disease, it's important that breeders are armed with the facts and that they still continue to use carrier dogs in their breeding programmes. Breeding a carrier with a non-carrier will not produce affected puppies; however, breeding just clear dogs with other clear dogs could reduce the gene pool within the breed and this could lead to other health problems in the future."

Canine Inherited Disorders Database: http://www.upei.ca/~cidd/Diseases/ocular%20disorders/keratoconjunctivitis%20sicca%20.htm http://www.upei.ca/cidd/Diseases/dermatology/ichthyosis.htm

Parallel Mapping and Simultaneous Sequencing Reveals Deletions in BCAN and FAM83H Associated with Discrete Inherited Disorders in a Domestic Dog Breed. Oliver P. Forman, Jacques Penderis, Claudia Hartley, Louisa J. Hayward, Sally L. Ricketts, and Cathryn S. Mellersh. PLoS Genet. 2012 January; 8(1): e1002462. Quote: "The domestic dog (Canis familiaris) segregates more naturally-occurring diseases and phenotypic variation than any other species and has become established as an unparalled model with which to study the genetics of inherited traits. We used a genome-wide association study (GWAS) and targeted resequencing of DNA from just five dogs to simultaneously map and identify mutations for two distinct inherited disorders that both affect a single breed, the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. We investigated episodic falling (EF), a paroxysmal exertion-induced dyskinesia, alongside the phenotypically distinct condition congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis (CKCSID), commonly known as dry eye curly coat syndrome. EF is characterised by episodes of exercise-induced muscular hypertonicity and abnormal posturing, usually occurring after exercise or periods of excitement. CKCSID is a congenital disorder that manifests as a rough coat present at birth, with keratoconjunctivitis sicca apparent on eyelid opening at 10-14 days, followed by hyperkeratinisation of footpads and distortion of nails that develops over the next few months. We undertook a GWAS with 31 EF cases, 23 CKCSID cases, and a common set of 38 controls and identified statistically associated signals for EF and CKCSID on chromosome 7 (Praw 1.9×10−14; Pgenome=1.0×10−5) and chromosome 13 (Praw 1.2×10−17; Pgenome=1.0×10−5), respectively. We resequenced both the EF and CKCSID disease-associated regions in just five dogs and identified a 15,724 bp deletion spanning three exons of BCAN associated with EF and a single base-pair exonic deletion in FAM83H associated with CKCSID. Neither BCAN or FAM83H have been associated with equivalent disease phenotypes in any other species, thus demonstrating the ability to use the domestic dog to study the genetic basis of more than one disease simultaneously in a single breed and to identify multiple novel candidate genes in parallel."

Congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis in Cavalier King Charles spaniel dogs - part II: candidate gene study. Claudia Hartley, Keith C. Barnett, Louise Pettitt, Oliver P. Forman, Sarah Blott, Cathryn S. Mellersh. Vet.Ophth. Sept. 2012;15(5):327-332. Quote: "Purpose: To identify causative mutation(s) for congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis (CKCSID) in Cavalier King Charles spaniel (CKCS) dogs using a candidate gene approach. Methods: DNA samples from 21 cases/parents were collected. Canine candidate genes (CCGs) for similar inherited human diseases were chosen. Twenty-eight candidate genes were identified by searching the Pubmed OMIM database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim). Canine orthologues of human candidate genes were identified using the Ensembl orthologue prediction facility (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html). Two microsatellites flanking each candidate gene were selected, and primers to amplify each microsatellite were designed using the Whitehead Institute primer design website (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/). The microsatellites associated with all 28 CCGs were genotyped on a panel of 21 DNA samples from CKCS dogs (13 affected and eight carriers). Genotyping data was analyzed to identify markers homozygous in affected dogs and heterozygous in carriers (homozygosity mapping). Results: None of the microsatellites associated with 25 of the CCGs displayed an association with CKCSID in the 21 DNA samples tested. Three CCGs associated microsatellites were monomorphic across all samples tested. Conclusions: Twenty-five CCGs were excluded as cause of CKCSID. Three CCGs could not be excluded from involvement in the inheritance of CKCSID."

Frequency of two disease-associated mutations in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, June 2012. Animal Health Trust. Quote: "In 2012 scientists at the Kennel Club Genetics Centre at the Animal Health Trust undertook a study to measure the frequency of the mutations responsible for congential keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis (dry eye and curly coat syndromd) and episodic falling in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels in the UK. This report describes the study, its conclusions and recommendations for breeders."

A Crosslinked HA-Based Hydrogel Ameliorates Dry Eye Symptoms in Dogs. David L. Williams, Brenda K. Mann. Int.J. of Biomaterials. 2013. Quote: "Keratoconjunctivitis sicca, commonly referred to as dry eye or KCS, can affect both humans and dogs. ... With immune-mediated KCS in dogs, there is a predisposition for specific breeds having a higher prevalence. These breeds include English Bulldogs, West Highland White Terriers, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, American and English Cocker Spaniels, and Pugs, with the prevalence reaching as high as 20% in these breeds. ... The standard of care in treating KCS typically includes daily administration of eye drops to either stimulate tear production or to hydrate and lubricate the corneal surface. Lubricating eye drops are often applied four to six times daily for the life of the patient. In order to reduce this dosing regimen yet still provides sufficient hydration and lubrication, we have developed a crosslinked hydrogel based on a modified, thiolated hyaluronic acid (HA), xCMHA-S. This xCMHA-S gel was found to have different viscosity and rheologic behavior than solutions of noncrosslinked HA. The gel was also able to increase tear breakup time in rabbits, indicating a stabilization of the tear film. Further, in a preliminary clinical study of dogs with KCS [including 3 CKCSs], the gel significantly reduced the symptoms associated with KCS within two weeks while only being applied twice daily. The reduction of symptoms combined with the low dosing regimen indicates that this gel may lead to both improved patient health and owner compliance in applying the treatment."

Investigation of two disorders in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. Chapter 3 of "Advances in genetic mapping and sequencing techniques: a demonstration using the domestic dog model." Oliver Forman PhD thesis pp 63-102, University of Glasgow. 2013.

A Mutation in the FAM83G Gene in Dogs with Hereditary Footpad Hyperkeratosis (HFH). Michaela Drogemüller, Vidhya Jagannathan, Doreen Becker, Cord Drogemüller, Claude Schelling, Jocelyn Plassais, Cecile Kaerle, Caroline Dufaure de Citres, Anne Thomas, Eliane J. Müller, Monika M. Welle, Petra Roosje, Tosso Leeb. PLOS Genetics. May 2014;10(5):e1004370. Quote: Hereditary footpad hyperkeratosis (HFH) represents a palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, which is inherited as a monogenic autosomal recessive trait in several dog breeds, such as e.g. Kromfohrlander and Irish Terriers. We performed genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in both breeds. In Kromfohrlander we obtained a single strong association signal on chromosome 5 (praw=1.0×10−13) using 13 HFH cases and 29 controls. The association signal replicated in an independent cohort of Irish Terriers with 10 cases and 21 controls (praw=6.9×10−10). The analysis of shared haplotypes among the combined Kromfohrlander and Irish Terrier cases defined a critical interval of 611 kb with 13 predicted genes. We re-sequenced the genome of one affected Kromfohrlander at 23.5× coverage. The comparison of the sequence data with 46 genomes of non-affected dogs from other breeds revealed a single private non-synonymous variant in the critical interval with respect to the reference genome assembly. The variant is a missense variant (c.155G>C) in the FAM83G gene encoding a protein with largely unknown function. It is predicted to change an evolutionary conserved arginine into a proline residue (p.R52P). We genotyped this variant in a larger cohort of dogs and found perfect association with the HFH phenotype. We further studied the clinical and histopathological alterations in the epidermis in vivo. Affected dogs show a moderate to severe orthokeratotic hyperplasia of the palmoplantar epidermis. Thus, our data provide the first evidence that FAM83G has an essential role for maintaining the integrity of the palmoplantar epidermis. ... However, a FAM83H frameshift variant in the last exon was shown to cause the autosomal recessive congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis (CKCSID), also called ''dry eye curly coat syndrome'', in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel dog breed. The apparent discrepancy in the reported phenotypes of human and dog patients with FAM83H variants might be due to the specific nature of the involved variants and calls for further investigations. In this context, it is interesting to note that the FAM83H mutant Cavalier King Charles Spaniels have a defect that shares several phenotypic features with the FAM83G mutant Kromfohrla¨nder and Irish Terriers, such as an altered coat texture, altered nails and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis.

Congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis in a

Cavalier King Charles spaniel with a single defective copy of the FAM83H

gene. JS Nimmo, E McMillan, G Sofronidis. Austral. Vet. Pract.

March 2020;50(1):41-45. Quote: A male neutered Cavalier King Charles

spaniel was presented initially because of pruritus, seborrhoea and otitis

externa

at about 15 months of age. The initial clinical diagnosis was

allergic dermatitis. Treatment with antibiotic and antifungal ear

preparations, prednisolone and cephalosporins over the following year did

not fully resolve the problem and the dog also developed a mucopurulent

conjunctivitis with keratoconjunctivitis sicca. The dermatological and

ophthalmological conditions prompted investigation for the condition known

as congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis

(CKCSID), which has been previously reported overseas in Cavalier King

Charles spaniels. Histopathology of skin biopsies confirmed the likelihood

of the latter diagnosis. Genetic testing was undertaken and established

that the dog was heterozygous for the disorder. ... Of particular

significance in the present case was the fact that the dog had only one

copy of the abnormal gene [FAM83H] and hence, assuming an

autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, should not have displayed clinical

signs. This raises the possibility, as was previously suggested,2 that the

mode of inheritance may not be a simple autosomal recessive, but may

involve partial or incomplete penetrance, modifying genes or it may be a

multi-gene lesion. ... The dermatosis and the

keratoconjunctivitis are being managed by ongoing symptomatic therapy, with

reasonable response to the former, however, the keratoconjunctivitis sicca

is expected to result in eventual blindness. ... Treatment with oclacitinib

maleate (16 mg

at about 15 months of age. The initial clinical diagnosis was

allergic dermatitis. Treatment with antibiotic and antifungal ear

preparations, prednisolone and cephalosporins over the following year did

not fully resolve the problem and the dog also developed a mucopurulent

conjunctivitis with keratoconjunctivitis sicca. The dermatological and

ophthalmological conditions prompted investigation for the condition known

as congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis

(CKCSID), which has been previously reported overseas in Cavalier King

Charles spaniels. Histopathology of skin biopsies confirmed the likelihood

of the latter diagnosis. Genetic testing was undertaken and established

that the dog was heterozygous for the disorder. ... Of particular

significance in the present case was the fact that the dog had only one

copy of the abnormal gene [FAM83H] and hence, assuming an

autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, should not have displayed clinical

signs. This raises the possibility, as was previously suggested,2 that the

mode of inheritance may not be a simple autosomal recessive, but may

involve partial or incomplete penetrance, modifying genes or it may be a

multi-gene lesion. ... The dermatosis and the

keratoconjunctivitis are being managed by ongoing symptomatic therapy, with

reasonable response to the former, however, the keratoconjunctivitis sicca

is expected to result in eventual blindness. ... Treatment with oclacitinib

maleate (16 mg

BID; Apoquel) was instigated to control the pruritus

associated with the ichthyosis. This is double the usual maintenance dose,

but lowering the dose resulted in the return of the pruritus and

self-trauma. The owners reported that this treatment was more effective

than the prednisolone had been. (It should be noted here that concurrent

atopic dermatitis can occur with CKCSID). The owners also cleansed the dog's

ears and paws twice daily, using Otoflush and Malaseb shampoo (Dermcare)

and reported that this was helpful in controlling pruritus. Nevertheless,

otitis externa that required medical treatment still tended to occur 3-4

times a year. Fifteen months after the histopathological confirmation of

the CKCSID diagnosis, the eyes had deteriorated further; corneal

vascularisation and opacity had developed. A veterinary ophthalmologist

reported it was difficult to see the anterior chamber, iris, lens and

vitreous. ... The prognosis therefore remains poor with ongoing vision loss

likely. ... Clinical cases of CKCSID are generally thought to be homozygous

for the genetic mutation, although this has been questioned in some

publications. The heterozygosity of the present case adds support to

another mode of expression.

BID; Apoquel) was instigated to control the pruritus

associated with the ichthyosis. This is double the usual maintenance dose,

but lowering the dose resulted in the return of the pruritus and

self-trauma. The owners reported that this treatment was more effective

than the prednisolone had been. (It should be noted here that concurrent

atopic dermatitis can occur with CKCSID). The owners also cleansed the dog's

ears and paws twice daily, using Otoflush and Malaseb shampoo (Dermcare)

and reported that this was helpful in controlling pruritus. Nevertheless,

otitis externa that required medical treatment still tended to occur 3-4

times a year. Fifteen months after the histopathological confirmation of

the CKCSID diagnosis, the eyes had deteriorated further; corneal

vascularisation and opacity had developed. A veterinary ophthalmologist

reported it was difficult to see the anterior chamber, iris, lens and

vitreous. ... The prognosis therefore remains poor with ongoing vision loss

likely. ... Clinical cases of CKCSID are generally thought to be homozygous

for the genetic mutation, although this has been questioned in some

publications. The heterozygosity of the present case adds support to

another mode of expression.

The Blue Book. Ocular Disorders Presumed to be inherited in purebred dogs. Genetics Committee of the American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists. Blue Book 15th Ed. 2023. pp. 297-302.

CONNECT WITH US