Brachycephalic Airway Obstruction Syndrome (BAOS)

in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel

-

What

It Is

What

It Is - Relation to Other Disorders

- Symptoms

- Diagnosis

- Care and Treatment

- Elongated Soft Palate

- Stenotic Nares

- Everted Laryngeal Saccules

- Laryngeal Collapse

- Pharyngeal Collapse

- Tracheal Collapse

- Sleep Disordered Breathing

- Other Disorders

- Breeders' Responsibilities

- Research News

- Related Links

- Dedication

- Veterinary Resources

What It Is

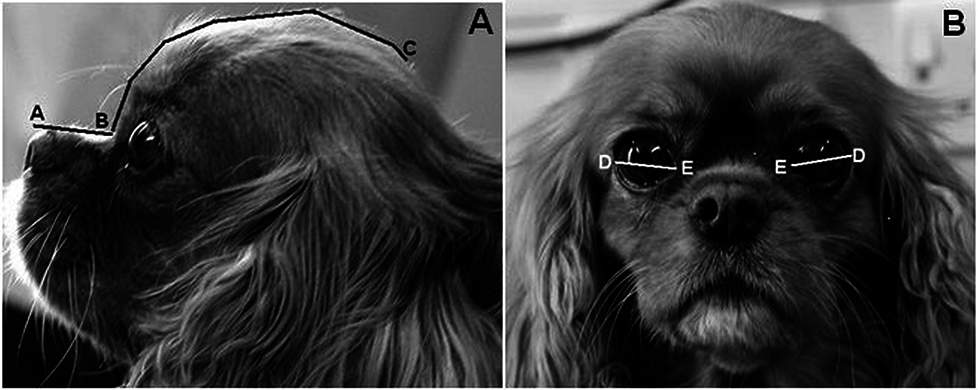

Brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome (BAOS)* is characterized by primary and secondary upper respiratory tract abnormalities, which may result in significant upper airway obstruction. BAOS is an inherited condition in the cavalier King Charles spaniel. The breed is pre-disposed to it, due to the comparatively short length of the cavalier's head and a compressed upper jaw**. (Skull at right below is of a cavalier.)

* BAOS is also

referred to as brachycephalic airway disease (BAD) and brachycephalic airway

syndrome (BAS) and even brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS).

** Until 2011,

there had been some dispute among researchers as to whether the cavalier King

Charles spaniel is a brachycephalic breed or a mesaticephalic (or mesocephalic)

breed. However, in a

2011 German study, the researchers

concluded that the CKCS was brachycephalic but that it had a wider braincase in

relation to length than in other brachycephalic breeds.

The term "brachycephalic" or "brachiocephalic" means short-headed and refers

to dogs with a shortened cranium (the bones that house the brain). Most

brachycepahic dogs have short muzzles and flat faces and noses which tip back

(airorhynchy) and a shorted lower jaw, but not necessarily.

The term "brachycephalic" or "brachiocephalic" means short-headed and refers

to dogs with a shortened cranium (the bones that house the brain). Most

brachycepahic dogs have short muzzles and flat faces and noses which tip back

(airorhynchy) and a shorted lower jaw, but not necessarily.

"Brachy" means short and "cephalic" means head. The throat and breathing passages in brachycephalic dogs often are undersized or flattened. The head's soft tissues are not proportionate to the shortened nature of the skull, and the excess tissues tend to increase resistance to the flow of air through the upper airway (nostrils, sinuses, pharynx and larynx).

This developmental defect is somewhat more apparent in a few other breeds: the English bulldog, pug, Boston terrier, and Pekingese, in particular. However, various degrees of BAOS predominate in the CKCS. The primary BAOS abnormalities in the cavalier include an elongated and fleshy soft palate, narrowed nostrils (stenotic nares), and everted laryngeal saccules, all of which are discussed in detail here. Other disorders may include laryngeal malformation and relatively small windpipe (tracheal hypoplasia or stenosis) and collapsing trachea*, and epiglottic retroversion, which are not specifically covered in this article. All of these disorders cause obstruction of the upper airway, compromise the dog's ability to take in air, and may result in laryngeal collapse. BAOS in the CKCS has been attributed by some researchers as a consequence of the selection for soft, puppy-like facial features, referred to as "morphological neoteny".

* Trachea collapse in the cavalier King Charles spaniel may also be due to an enlarged heart caused by advanced mitral valve disease. Also, a 2004 study by researchers at the Royal Veterinary College found that 53% of the brachycephalic dogs in their 92 dog sample had heart disease, compared to 24% of the non-brachycephalic dogs. See Mitral Valve Disease.

In a 2010 report of BAOS surgery on 155 Australian dogs, the cavalier was the most common breed (29 dogs, 18.7%). The researchers found: "All CKCS had an elongated soft palate and accounted for 41% of the laryngeal collapse cases."

RETURN TO TOP

Relation to Other Disorders

In a 2010 report, UK researchers found an association between primary secretory otitis media (PSOM) and brachycephalic conformation in cavaliers. They stated: "In CKCS, greater thickness of the soft palate and reduced nasopharyngeal aperture are significantly associated with OME [otitis media with effusion, meaning PSOM]." However, they did not explain why PSOM is so nearly limited to the cavalier, while so many other breeds are brachycephalic. They also concluded that bilateral PSOM was associated with CKCS with more extreme nasopharyngeal conformation, than unaffected CKCS.

Robert N. White, a board certified veterinary soft tissue surgeon practicing at Willows Veterinary Centre and Referral Service in Solihull, West Midlands, observed in an October 2010 presentation before a meeting of the UK's Association of Veterinary Soft Tissue Surgeons, that the cavalier King Charles spaniel does not appear to be a classically brachycephalic breed, despite the extent of BAOS in the cavalier, and that the extent of both primary secretory otitis media (PSOM) and syringomyelia (SM) in the breed suggests that the CKCS may suffer from a combination syndrome of the three disorders, all associated with Chiari-like malformation.

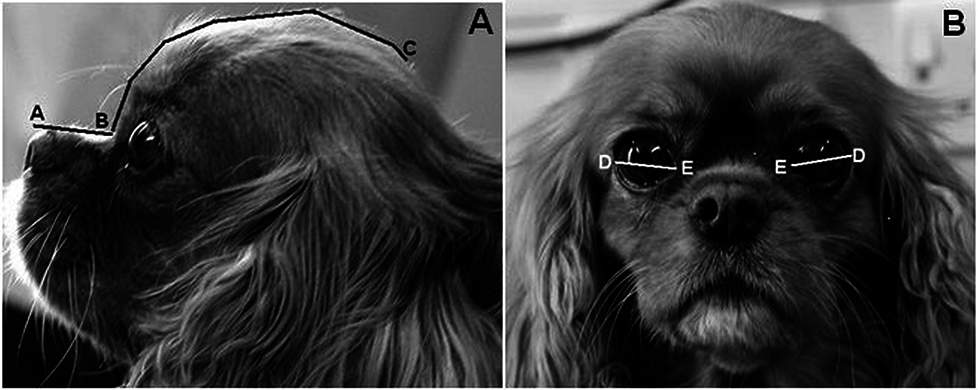

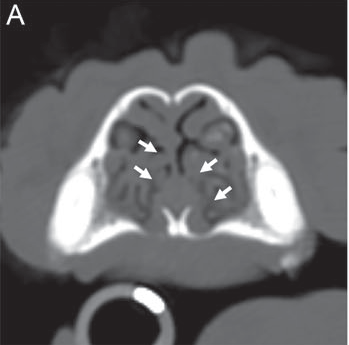

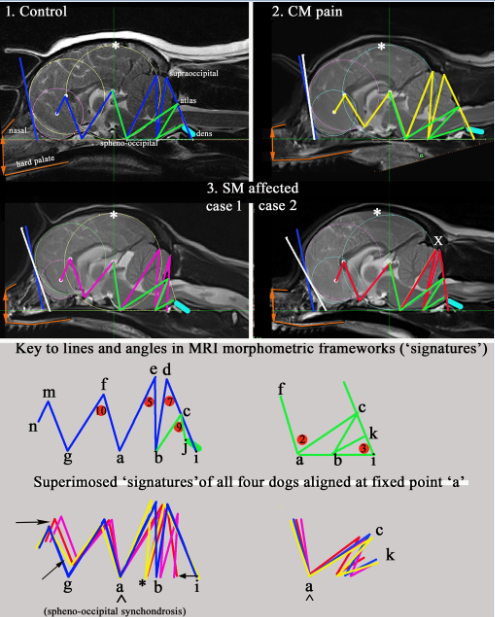

In a January 2017 article, UK researchers found evidence that pain resulting from Chiari-like malformation (CM) is associated with increased brachycephaly, and syringomyelia (SM) can result from different combinations of abnormalities of the forebrain, caudal fossa, and craniocervical junction which compromise the neural parenchyma and impede cerebrospinal fluid flow.

In a December 2022 article, ophthalmologists attribute the high prevalence of both dry eye syndrome and corneal ulcers in cavaliers to BAOS.

BAOS is linked directly to esophagus disorders, including gastroeosophageal reflux disease (GERD) and megaesophagus.

RETURN TO TOP

Overall Symptoms

The symptoms may vary and range in severity, depending upon which abnormality is causing them, but they typically include:

• labored and constant open mouthed breathing

• noisy breathing

• snuffling

• snorting

• excessive or loud snoring

• gagging

• retching

• gastroesophageal reflux

• sleep apnea

• exercise and/or heat intolerance

• general lack of energy

• pale or bluish tongue and gums due to a lack of oxygen

Audible breathing noises when inhaling, such as a high-pitched (stridor) or low pitched noise (stertor) likely is symptomatic of upper respiratory tract disease. Stridor, the high-pitched noise, is associated with upper airway obstruction and disease of the oropharynx or larynx. Stertor, the lower-pitched noise, is similar to snoring and would be associated with disease of the nasal cavity or nasopharynx.

In an April 2018 abstract, a team of UK veterinary surgeons reported their study of five cavaliers which had been suffering from obstructive sleep apnea (apnoea). Apnea means the suspension of breathing due to blocked airways. Previously, it had been reported only in English bulldogs, French bulldogs, and pugs, all typically severely brachycephalic breeds. All five CKSCs suffered from heavy snoring and noisy breathing and choking, as well as sleep apnea. In addition, all five had eosinophilic stomatitis and primary secretory otitis media (PSOM); four had mitral valve disease (MVD); and three had syringomyelia (SM). Also, all five had "aberrant nasal turbinates, nasal septal deviation and soft palate thickening and 3/5 had nasopharyngeal thickening and tracheal collapse."

Also, studies have concluded that brachycephalic dogs may be predisposed to the conditions of Primary Secretory Otitis Media (PSOM), and eye problems, such as entropion, dry eye, and other disorders which may be caused by eyes not properly seated in the skull.

RETURN TO TOP

Overall Diagnosis

A variety of methods and devices are useful in diagnosing respiratory disorders related to BAOS.

• Respiratory sounds may be distinguished with or without a stethoscope. Noisy breathing, called stertor or stridor sounds, indicate the location of the problem is in the upper airway. Stertor points to a nasopharyngeal disorder, while stridor indicates the arynx or upper trachea. Wheezes ususally indicate narrowing of the lower airway. Stethoscopes can pick up crackles associated with the lungs.

• X-rays (thoracic radiography) will help determine the location and extent of the disease.

• Fluorscopic dynamic imaging is used to assess the extent of upper airway collapse, including that of the trachea, bronchus, pharynx, and epiglottis.

• Bronchoscopy is the preferred device for detecting airway collapse. Anesthesia is required for this device.

• Computed tomography (CT) can locate disorders of the nasal cavity and thorax airways. Anesthesia is required for this device.

• Rhinoscope visualizes nasal pasages and the nasopharynx..

RETURN TO TOP

Overall Care and Treatment

The brachycephalic cavalier is an inefficient panter. Increased panting can cause swelling and narrowing of the airway, resulting in collapsing or fainting. The excessive panting and episodes of other symptoms may place increased strain on the dog's heart, which cavaliers with mitral valve disease cannot afford to risk.

Care should be taken to avoid overheating and excessive excitement and excessive exercise, which may cause increased panting. Excessive barking or panting may cause the throat to swell, which could result in a totally blocked airway. Most importantly, the owner should not let the dog get too hot, particularly in the summer months, and not allow the dog to become overweight, as obesity will exacerbate the respiratory difficulties. Death from such related causes as heat stroke may be the consequence of not diagnosing and treating these symptoms early enough.

Care also should be taken when anesthesia may have to be

administered. In a March 2012 report

by a team of Tufts University veterinary anesthesiologists, cavaliers are among

brachycephalic breeds which require special attention when being sedated and

anesthetized. Their advice includes:

Care also should be taken when anesthesia may have to be

administered. In a March 2012 report

by a team of Tufts University veterinary anesthesiologists, cavaliers are among

brachycephalic breeds which require special attention when being sedated and

anesthetized. Their advice includes:

"Avoid excessive sedation. Avoid α2-agonists. Administer acepromazine at half dose. Preoxygenate. Use short-acting induction agent. Use appropriately sized endotracheal tubes. Extubate after patient is sitting up, vigorously chewing, bright, alert."

See also our webpage on anesthesia and sedatives.

In mild episodes, calming and cooling the dog may be sufficient. Inflammation and swelling of the airway tissues (oedema) may be treated with oxygen therapy (see photo) and corticosteroids for short term relief. Surgery is required when the abnormalities chronically interfere with breathing. Following surgery, the dog will need to be monitored closely for at least the first 24 hours, because inflammation or bleeding can obstruct the airway, making breathing difficult or impossible.

In all cases, it is strongly recommended that only board certified veterinary surgeons (who also are very experienced at airway surgery) be permitted to perform any type of airway surgery on cavaliers.

Unfortunately, the only solution to most cases of BAOS is some form

of surgery. In a

June 2016 article, the Spanish specialist definitively states:

Unfortunately, the only solution to most cases of BAOS is some form

of surgery. In a

June 2016 article, the Spanish specialist definitively states:

"The definitive treatment for the BS [brachycephalic syndrome] is always surgical. Early intervention can slow down the progression of the signs and complications. There are several surgical techniques and, during the last years, the use of CO2 laser ensures less surgical time, bleeding, swelling and intra and postoperative pain, as well as a more precise tissue ressection. A possible explanation for the poor therapeutic success after conventional surgeries, could be the lack of consideration in the diagnosis, management and treatment of the rest of intranasal structures. To understand the BS, all the efforts should relapse into the selection of these breeds, so that in the future, the objective is to encourage more moderate craniofacial morphologies in order to reduce the prevalence and severity of BS."

RETURN TO TOP

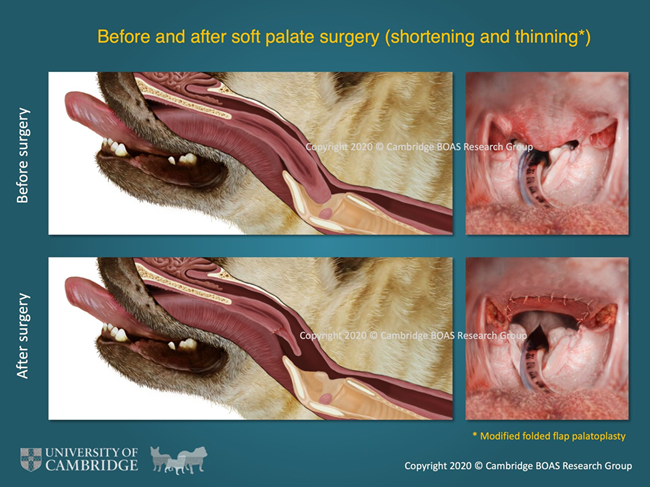

Elongated & Fleshy Soft Palate -- Reverse Sneeze

-- what it is

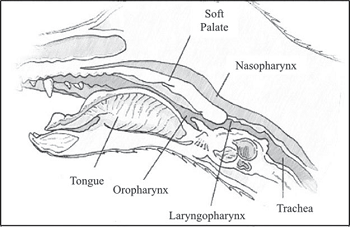

The

palate is the roof of the mouth. It is divided into two parts, the anterior

(front) bony

hard palate, and the posterior (rear) fleshy soft palate. The soft palate separates the

nasal passage from the oral cavity. An elongated soft palate is too long for the

length of the mouth, so that its tip protrudes into the front of the airway and

may get sucked into the laryngeal opening where it may obstruct the normal

passage of air into the trachea. A fleshy soft palate is an

abnormally thick one which reduces the dimension of the nasal air passage way.

(See the soft palate at the top of the sketch, right.)

The

palate is the roof of the mouth. It is divided into two parts, the anterior

(front) bony

hard palate, and the posterior (rear) fleshy soft palate. The soft palate separates the

nasal passage from the oral cavity. An elongated soft palate is too long for the

length of the mouth, so that its tip protrudes into the front of the airway and

may get sucked into the laryngeal opening where it may obstruct the normal

passage of air into the trachea. A fleshy soft palate is an

abnormally thick one which reduces the dimension of the nasal air passage way.

(See the soft palate at the top of the sketch, right.)

RETURN TO TOP

-- symptoms

The most common and recurrent symptom of an elongated or

fleshy soft palate is noisy

breathing. Occasionally, the dog will make snorting sounds, which is due to the

tip of the palate flapping into the trachea

during respiration. This is called

the "Cavalier snort" or a "reverse sneeze".* The dogs also are more likely to

snore, gag, or retch, and in severe instances, they may collapse if the airflow

is obstructed completely. See an example of a cavalier reverse sneezing at

this

YouTube video. See also, our blog entry,

All that cavalier owners need to know about the "Reverse Sneeze" or "Cavalier

Snort".

during respiration. This is called

the "Cavalier snort" or a "reverse sneeze".* The dogs also are more likely to

snore, gag, or retch, and in severe instances, they may collapse if the airflow

is obstructed completely. See an example of a cavalier reverse sneezing at

this

YouTube video. See also, our blog entry,

All that cavalier owners need to know about the "Reverse Sneeze" or "Cavalier

Snort".

* It may be confused with pharyngeal gag reflex or inspiratory proxysmal respiration.

Reverse sneezes may occur due to any of a variety of causes, such as foreign bodies, airborne irritation, or growths in the nasal passage. These possible causes need to be eliminated during the diagnosis procedures.

Cavaliers with abnormally thick soft palates also are more likely to develop primary secretory otitis media (PSOM), due to the size of the soft palate impairing auditory tube drainage. See this July 2010 article.

RETURN TO TOP

-- diagnosis

In severe cases, the palate usually is examined with the dog under light general anesthesia, using a laryngoscope. An elongated palate will obstruct the view of the larynx when the tongue is depressed. The veterinarian may take an x-ray to determine the length of the palate and airway.

RETURN TO TOP

-- treatment

If the palate is only moderately elongated and does not totally block the

trachea, most cavaliers are able to pull out of these blockages by themselves. Snorting may be relieved by forcing the cavalier to breathe through its

mouth instead of its nose. This may be done by holding the dog's head down and

mouth open with one hand while blocking air from entering the nose with the

other hand.

If the palate is only moderately elongated and does not totally block the

trachea, most cavaliers are able to pull out of these blockages by themselves. Snorting may be relieved by forcing the cavalier to breathe through its

mouth instead of its nose. This may be done by holding the dog's head down and

mouth open with one hand while blocking air from entering the nose with the

other hand.

Treatment for recurring blockage of airflow is surgical removal of excess tissue from the palate by a veterinary surgeon. The standard surgical procedure is called a staphylectomy, which is the removal of a portion of the soft palate at its juncture with the epiglottis, and then a resectioning.

Another surgical procedure is "folded flap palatoplasty" (FFP), which both shortens and thins the soft palate. Others are carbon dioxide laser for resectioning, and harmonic scalpels. See this November 2011 article and this October 2017 article for additional details.

Post surgery prognosis is good for young dogs. They generally may be expected to breathe much easier, with significantly reduced respiratory distress, and display more energy and stamina. Older dogs may have a less favorable prognosis. However, in this November 2011 article, there is this report of a very successful 5 minute surgery on a 7 year old CKCS:

"A 7-year-old male neuter Cavalier King Charles Spaniel was presented with moderate respiratory compromise secondary to BAOS. The patient had a history of slowly worsening inspiratory obstruction and was becoming increasingly exercise intolerant. The nares were not stenotic and the laryngeal saccules appeared normal. Under general anaesthesia it was judged that the soft palate was 5 mm too long and surgery was performed to resect the redundant tissue. The staphylectomy took 5 min without complications. The modified surgical procedure was used in this case and the patient recovered uneventfully, with no postoperative bleeding or respiratory compromise. Respiratory function was much improved at recovery from anaesthesia and at 24 h. The patient was virtually asymptomatic 6 months postoperatively."

In all cases, it is strongly recommended that only board certified veterinary surgeons (who also are very experienced at airway surgery) be permitted to perform any type of airway surgery on cavaliers.

In a 2010 report of BAOS surgery on 155 Australian dogs, the cavalier was the most common breed (29 dogs, 18.7%). All of those cavaliers had an elongated soft palate.

RETURN TO TOP

Stenotic Nares

-- what they are

Stenotic nares are abnormally narrow or obstructed nostrils

(right), especially when

inhaling. Dogs with this disorder tend to breathe primarily through their

mouths, because breathing through the nose is unproductive. When they do breathe

through their noses, they make wheezing sounds. Stenotic nares cause the dog to

inhale deeper to draw air through the nose and into the lower airway, which may

contribute to the development of secondary abnormalities, such as

everted laryngeal saccules and

laryngeal collapse.

Stenotic nares are abnormally narrow or obstructed nostrils

(right), especially when

inhaling. Dogs with this disorder tend to breathe primarily through their

mouths, because breathing through the nose is unproductive. When they do breathe

through their noses, they make wheezing sounds. Stenotic nares cause the dog to

inhale deeper to draw air through the nose and into the lower airway, which may

contribute to the development of secondary abnormalities, such as

everted laryngeal saccules and

laryngeal collapse.

RETURN TO TOP

-- symptoms

The dog's nose appears narrow, with the nostril wings (alar folds) collapsing inward during inhalation and possibly blocking the nares. As noted above, the dog tends to breathe through its mouth, and makes wheezing sounds when breathing with its mouth closed. Symptoms typically include labored and constant open mouthed breathing, noisy breathing, snuffling, snorting, excessive snoring, and in severe cases, gagging, retching, exercise and/or heat intolerance, pale or bluish tongue and gums due to a lack of oxygen.

RETURN TO TOP

-- diagnosis

Stenotic nares are easily diagnosed by visual examination. In severe cases, the flow of air through the nostrils may be so poor that no air movement can be detected.

RETURN TO TOP

-- treatment

Surgery under general anesthesia is the preferred means of treating stenotic

nares. Surgical techniques for widening the nares include: alapexy, punch

resection, partial amputation of the nasal cartilage, dorsal offset rhinoplasty,

and multiple variations of wedge excision of the ala nasi. The aim is to increase the size of the nostrils by removing tissue from

the wings and possibly some related cartilage.

Surgery under general anesthesia is the preferred means of treating stenotic

nares. Surgical techniques for widening the nares include: alapexy, punch

resection, partial amputation of the nasal cartilage, dorsal offset rhinoplasty,

and multiple variations of wedge excision of the ala nasi. The aim is to increase the size of the nostrils by removing tissue from

the wings and possibly some related cartilage.

In an August 2020 article, USA surgeons report surgically repairing the stenotic nares of 34 brachycephalic dogs, including one cavalier, using the dorsal offset rhinoplasty (DOR) technique. DOR involves removing a wedge of nasal planum and cartilage from each nare, opening the nares.

Post surgery recovery is similar to that described above under Overall Care and Treatment and treatment for elongated soft palate. Following surgery, the dog will be required to wear an Elizabethan collar to keep the surgical site clean and to protect it from rubbing.

In all cases, it is strongly recommended that only board certified veterinary surgeons (who also are very experienced at airway surgery) be permitted to perform any type of airway surgery on cavaliers.

RETURN TO TOP

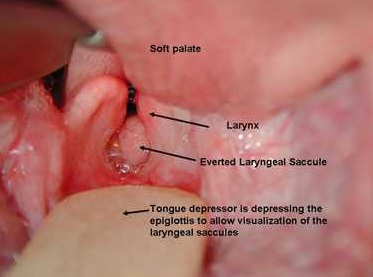

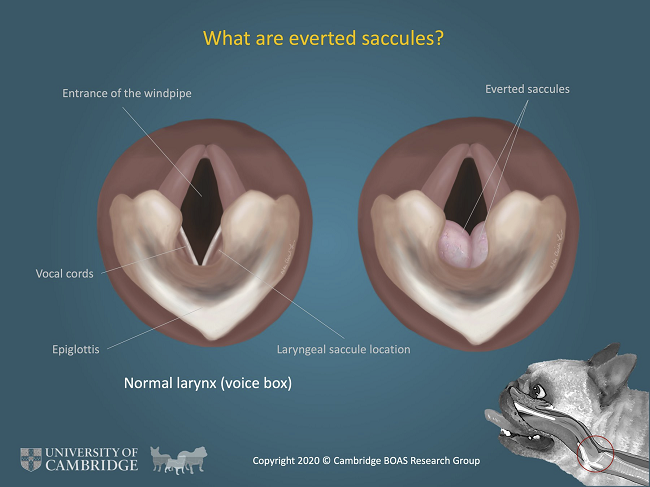

Everted Laryngeal Saccules

-- what they are

Everted laryngeal saccules are a secondary abnormality to either an elongated

soft palate or stenotic nares. The larynx contains the vocal chords, produces

sound, and protects the trachea. It is located at the point where the upper

tract divides into the trachea and the esophagus. During swallowing, the larynx

closes to prevent swallowed material from entering the lungs. The laryngeal

saccules are part of the mucosal lining of the laryngeal ventricles and appear

as two membranous sacs that are located in recessions in front of the vocal

folds.

Everted laryngeal saccules are a secondary abnormality to either an elongated

soft palate or stenotic nares. The larynx contains the vocal chords, produces

sound, and protects the trachea. It is located at the point where the upper

tract divides into the trachea and the esophagus. During swallowing, the larynx

closes to prevent swallowed material from entering the lungs. The laryngeal

saccules are part of the mucosal lining of the laryngeal ventricles and appear

as two membranous sacs that are located in recessions in front of the vocal

folds.

Brachycephalic cavaliers must create more pressure when they inhale in order to fill their lungs with air. This decreases the pressure in the upper airway, causes the lining of the larynx (laryngeal ventricles) to swell, and forces the laryngeal saccules to vibrate and evert into the airway at the opening to the trachea, blocking the flow of air. Everted laryngeal saccules usually are the first stage of laryngeal collapse.

RETURN TO TOP

-- symptoms

The symptoms are those common to a lack of air intake, such as gagging, retching, fainting, pale or bluish tongue and gums due to a lack of oxygen.

RETURN TO TOP

-- diagnosis

Everted laryngeal saccules are diagnosed under anesthesia. They appear as bilateral, red, fleshy, globular sacs.

RETURN TO TOP

-- treatment

Tissue from the saccules are surgically removed under general anesthesia. This procedure is called a "laryngeal sacculectomy". A tube will be inserted through the neck into the trachea ("temporary tracheostomy") to allow an airway during surgery and will remain until the swelling in the throat subsides enough that the dog can breathe normally. Post surgery and recovery are similar to that described above under under Overall Care and Treatment and treatment for elongated soft palate.

In all cases, it is strongly recommended that only board certified veterinary surgeons (who also are very experienced at airway surgery) be permitted to perform any type of airway surgery on cavaliers.

RETURN TO TOP

Laryngeal Collapse

-- what it is

Laryngeal collapse is an advanced form of brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome.* The primary conditions of stenotic nares and elongated soft palate, together with everted laryngeal saccules, lead to abnormal stresses on the larynx and a progressive distortion and ultimate collapse of the cartilage supporting the larynx. There are three stages (grades) of laryngeal collapse, Stage 1 (Grade 1) being the everted laryngeal saccules described above. Stage 2 (Grade 2) occurs when the arytenoid cartilage loses its rigidity and gradually collapses inwardly. The third and final stage (Grade 3) is when the cartilage fails completely, and the larynx collapses.

* A similar condition is tracheal collapse, which appears less common in the CKCS. Also, laryngeal paralysis.

In a 2010 report of BAOS surgery on 155 Australian dogs, the cavalier was the most common breed (29 dogs, 18.7%). The researchers found: "All CKCS had an elongated soft palate and accounted for 41% of the laryngeal collapse cases."

RETURN TO TOP

-- symptoms

When the larynx collapses, the cavalier will not be able to breathe at all. The situation will be an extreme, life-threatening emergency.

RETURN TO TOP

-- diagnosis

The diagnosis is made by visual examination using a laryngoscope while the dog is under light anesthesia. A laryngoscope is a thin tube with a light, lens, and a video camera. Radiiography (X-rays) of the laryngeal ventricles is being researched as another diagnositic device. It involves measuring the ratios of the ventricular length and surface to the length of the third cervical vertebra (MVL/LC3 and VS/LC3).

RETURN TO TOP

-- treatment

Depending upon the severity of the collapse, an early option may be a partial laryngectomy to enlarge the laryngeal opening. The procedure will include anesthesia and a temporary tracheostomy. Statistical studies have shown that less than 50% of dogs treated this way survive, due to the permanent cartilage deformation and softening which results in continued collapse.

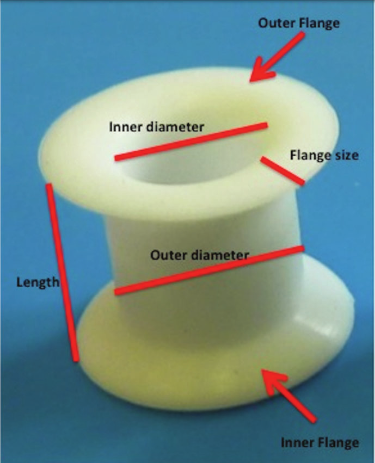

Permanent tracheostomy has the only other option until recently. A permanent tracheostomy creates a permanent opening (a stoma) through the neck into the trachea (windpipe). A tracheostomy tube or trach tube is placed through the stoma to provide an airway and to remove secretions from the lungs. Prognosis is poor, particularly for older dogs.

Recently, other surgical options fot treating advanced laryngeal collapse include cricoarytenoid lateralization with thyroarytenoid caudolateralisation or alternatively via partial cuneiformectomy, partial laryngectomy (reduceing dynamic obstruction and widening the rima glottidis by approximately 70%-80%, and, arytenoidectomy (using laser photoablation). For details on thses procedures, see this June 2025 article.

In a June 2018 article about permanent tracheostomies performed on 15 brachycephalic dogs with severe laryngeal collapse, a team of Italian veterinary surgeons reported on three surgeries required to resolve grade 3 laryngeal collapse in a cavalier King Charles spaniel. The CKCS was an 11 year old female. The first procedure shorted the dog's elongated soft palate. A month later, the surgeons resected the cavalier's hypertrophic aryepiglottic folds surrounding the larynx. A month after the second procedure, the surgeons performed a permanent tracheostomy, which creates a permanent opening (a stoma) through the neck into the trachea (windpipe). A tracheostomy tube or trach tube is placed through the stoma to provide an airway and to remove secretions from the lungs. The CKCS survived the three surgeries successfully and lived another 143 days, dying by euthanasia due to a separate medical disorder.

A 2014 report examined the insertion of silicone tracheal stoma stents for temporary tracheostomy in eighteen dogs with upper airway obstruction, including three cavaliers. The conclusion was that use of the stent beyond five days was not recommended because of granulation tissue formation, and that the long-term consequences of partial tracheal ring resection are unknown.

In all cases, it is strongly recommended that only board certified veterinary surgeons (who also are very experienced at airway surgery) be permitted to perform any type of airway surgery on cavaliers.

RETURN TO TOP

Pharyngeal Collapse

-- what it is

The

pharynx is the dog's throat, a muscular membrane tube that extends from

the soft palate at the back of the tongue and nasal cavity and larynx

down to the where its trachea and esophagus come together. It has three

regions, the nasopharynx at its top, the oropharynx at its center behind

the mouth, and the laryngopharynx at its bottom. The nasopharynx is

connected to the nasal cavities and is the air passage during breathing

and also connects to the openings of the eustachian tubes through which

air enters the middle ear. The oropharynx and laryngopharynx are

passageways for both air and food. (See diagram from

Rubin et al., at right.)

The

pharynx is the dog's throat, a muscular membrane tube that extends from

the soft palate at the back of the tongue and nasal cavity and larynx

down to the where its trachea and esophagus come together. It has three

regions, the nasopharynx at its top, the oropharynx at its center behind

the mouth, and the laryngopharynx at its bottom. The nasopharynx is

connected to the nasal cavities and is the air passage during breathing

and also connects to the openings of the eustachian tubes through which

air enters the middle ear. The oropharynx and laryngopharynx are

passageways for both air and food. (See diagram from

Rubin et al., at right.)

When pharyngeal collapse occurs, the tube is weakened and narrows, particularly at the nasopharynx. It may occur upon inhaling or upon exhaling, depending upon the underlying cause. Pharyngeal collapse is not believed to be a primary disease and instead a complication of other airway disorders. Negative airway pressure upon inhalation and increased pressure upon exhalation, due to the underlying primary disorder, can cause the pharynx to collapse, either partially or completely. In general, brachycephalic dogs suffering from an elongated soft palate or everted laryngeal saccules or stenotic nares, can affect pharyngeal diameter.

RETURN TO TOP

-- symptoms

The most common sign is coughing, followed by snoring, gagging, regurgitation of food, and sneezing. Sleep disordered breathing, in particluar apnea, may also be attributed to pharyngeal collapse upon exhaling.

RETURN TO TOP

-- diagnosis

Fluoroscopy (or videofluoroscopy), which shows a continuous x-ray image, so that the pharynx can be viewed in motion upon inhaling and exhaling, can confirm pharyngeal collapse. The dog is awake during this procedure, although it may be sedated. Computed tomography (CT) scans can assess structural abnormalities in the pharynx.

RETURN TO TOP

-- treatment

Since pharyngeal collapse usually is secondary to an underlying disorder, treatment usually is of that primary cause.

In an April 2021 article, a 4-year-old female cavalier King Charles spaniel diagnosed with partial pharyngeal collapse experienced sleep apnea episodes every 10 to 15 minutes during sleep. The dog was fitted with a "continuous positive airway pressure" (CPAP) device, which included a mask connected to an air hose and pump, to create a mild positive pressure in the dog's airway. (See Figures 1 & 2.) A muzzle was fitted over the mask to secure it to the dog's head. The cavalier gradually got accustomed to the device, with the owner using positive reinforcement with treats and removing the apparatus before the dog displayed signs of distress. Eventually, after continuing to suffer SDB episodes without the device, the dog sought out the mask and muzzle. With the CPAP device in place, the cavalier was able to sleep between 4 to 5 hours each night.

RETURN TO TOP

Tracheal Collapse

-- what it is

-- what it is

The trachea is a flexible tube that connects the larynx with the mainstem bronchi. The tube is composed of 35 to 45 C-shaped rings of cartilage, held by the trachealis muscle and membranes. The trachea is commonly referred to as the windpipe. The interior airspace of the trachea is called the tracheal lumen. The trachea transports air through its lumen to and from the lungs during respiration and also transports debris to the larynx.

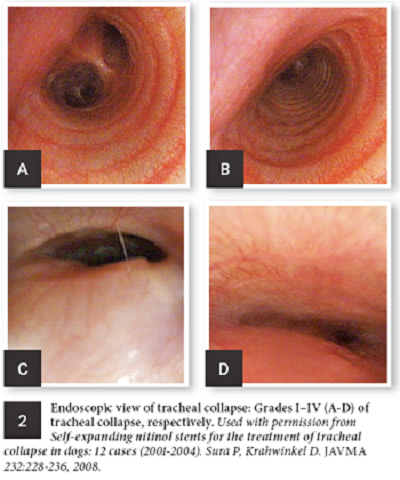

Tracheal collapse is a progressive flattening of the tracheal lumen. It begins with the trachealis muscle weakening and progresses to the C-shaped rings becoming more egg-shaped, resulting in the lumen to narrow and flatten. (See set of endoscopic views at right.)

The severity of tracheal collapse is graded based upon the percentage of blockage of the lumen: from Grade I (<25%), to Grade II (<50%) to Grade III (<75%) to Grade IV (up to 100% or complete blockage).

RETURN TO TOP

-- symptoms

The most common sign is coughing, particularly a goose-like honking, noisy breathing, then difficulty breathing, bluish discoloration of the tongue and/or gums, and high body temperature. The trachea changes postion, its cartilege may make a clicking sound when the dog breathes.

Obesity can contribute to the severity of these symptoms, due to causing more rapid respiration and effort to breathe.

Note that in cases of cavaliers with mitral valve disease (MVD) with heart enlargement, the enlarged left atrium (LA) may press against the trachea and cause the dog to cough as if the trachea has collapsed.

RETURN TO TOP

-- diagnosis

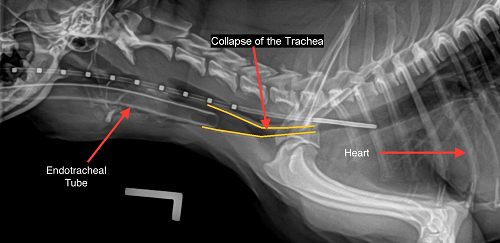

X-rays

are the quickest and least expensive method of detecting a

collapsing trachea. (See x-ray at right from the

Univ. of Missouri.)

X-rays

are the quickest and least expensive method of detecting a

collapsing trachea. (See x-ray at right from the

Univ. of Missouri.)

Fluoroscopy (or videofluoroscopy), which shows a continuous x-ray image, so that the trachea can be viewed in motion upon inhaling and exhaling, can confirm tracheal collapse. The dog is awake during this procedure, although it may be sedated. Computed tomography (CT) scans can assess structural abnormalities in the trachea. Other methods include ultrasound and tracheobronchoscopy.

RETURN TO TOP

-- treatment

Most dogs having tracheal collapse are medicated, primarily with a cough suppressant/antitussive (diphenoxylate hydrochloride and atropine sulfate [Logen, Lomotil, Lonox, Lofenoxal], hydrocodone, butorphanol, codeine phosphate) to reduce the frequency of coughing. Corticosteroids, such as stanozolol, my be added to reduce inflammation resulting from the collapse. Secondary airway infections will require antibiotics (doxycycline, cephalexin, or amoxicillin-clavulanate). Bronchodilators (theophylline, albuterol* [salbutamol] and , terbutaline, aminophylline) and/or antihistamines may also be prescribed.

* Albuterol (salbutamol) reportedly is toxic to some dogs, especially the aerosolized version. Toxicity symptoms have included tachycardia or other arrhythmia, weakness, lethargy, tachypnea, aggression, agitation, hyperactivity, vomiting, tremors and seizures.

More severe cases will require tracheal stent implantation inside the lumen. Stents are woven and self-expanding, made of the nickel-titanium alloy nitinol. The stent is inserted by means of a catheter.

Overweight dogs may be expected to benefit from weight loss. Neck collars and neck leads should be avoided, and instead a harness should be used when walking the dog, to avoid pressure acraoss the neck. Difficulty breathing and/or a bluish tongue will require oxygen supplementation, injected corticosteroids, and sedatives.

RETURN TO TOP

Sleep Disordered Breathing

Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) refers to any breathing difficulties which occur while the dog is asleep. They range from snoring due to partial obstructions to apena, which is the complete cessation of breathing. In cavalier King Charles spaniels, it most often is attributable to BAOS.

In a February 2024 article, a team of Finnish researchers evaluated the risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in serveral dog breeds. Of 28 brachycephalic dogs, 8 (28.5%) were cavalier King Charles spaniels. Other SDB breeds comprised 35 dogs. They reported that "We had an overrepresentation of Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, French Bulldogs and Labrador Retrievers." They found that brachycephaly was a significant risk factor for SDB, particularly apnea, and BOAS-positive class (moderate or severe BOAS signs) was a significant risk factor, along with excess weight. Aging and Chiari-like malformation were not risk factors among the dogs in this study.

• Apnea

Apnea means the complete suspension of breathing due to blocked airways. In dogs, it also is called obstructive sleep apnea because it usually is attributed to obstruction of the brachycephalic dog's upper airway, a sign of brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome (BAOS). This form of apnea is most common among English bulldogs, French bulldogs, and pugs, all typically severely brachycephalic breeds, but has been observed in cavalier King Charles spaniels as well.

Symptoms of apena include interrupted sleep, choking, and other signs

that the dog has ceased to breathe. The dog may wake up in distress,

gasping. It may sleep with its chin elevated or mouth open to compensate

for the

disorder.

in most cases, the cavalier has been diagnosed with nasal septum

deviation (NSD). The septum is comprised of bone and cartilage,

which divides the right and left nostrils (nares) and airways of the

nasal cavity. Deviation of the septum means that the septum is misplaced

and one or both of the nostrils is abnormally small. See this

March 2022 article.

disorder.

in most cases, the cavalier has been diagnosed with nasal septum

deviation (NSD). The septum is comprised of bone and cartilage,

which divides the right and left nostrils (nares) and airways of the

nasal cavity. Deviation of the septum means that the septum is misplaced

and one or both of the nostrils is abnormally small. See this

March 2022 article.

In severe cases, the treatment option is limited to surgery of the portion of the airway causing the obstruction, typically at the nasal entrance, nasal cavity, pharynx, and/or larnynx. (See photo.)

In an April 2018 abstract and a May 2019 article, a team of UK veterinary surgeons reported their study of five cavaliers which had been suffering from obstructive sleep apnea (apnoea). All five CKSCs suffered from heavy snoring and noisy breathing and choking, as well as sleep apnea. In addition, all five had eosinophilic stomatitis and primary secretory otitis media (PSOM); four had mitral valve disease (MVD); and three had syringomyelia (SM). Also, all five had "aberrant nasal turbinates, nasal septal deviation and soft palate thickening and 3/5 had nasopharyngeal thickening and tracheal collapse."

In an April 2021 article, a 4-year-old female cavalier King Charles spaniel diagnosed with partial pharyngeal collapse experienced sleep apnea episodes every 10 to 15 minutes during sleep. The dog was fitted with a "continuous positive airway pressure" (CPAP) device, which included a mask connected to an air hose and pump, to create a mild positive pressure in the dog's airway. (See Figures 1 & 2.) A muzzle was fitted over the mask to secure it to the dog's head. The cavalier gradually got accustomed to the device, with the owner using positive reinforcement with treats and removing the apparatus before the dog displayed signs of distress. Eventually, after continuing to suffer SDB episodes without the device, the dog sought out the mask and muzzle. With the CPAP device in place, the cavalier was able to sleep between 4 to 5 hours each night.

In a December 2024 article, a 4-year-old cavalier diagnosed with SDB had these symptoms:

"The dog exhibited apneic episodes during sleep, followed by abrupt waking, gasping, disorientation, and screaming. These episodes occurred exclusively in the evening around once a night, and the patient was otherwise normal during the day."

Initially, the CKCS was treated with zonisamide for seizures, without success. Then, it was found to have a mildly elongated soft palate and no evidence of laryngeal collapse. A staphylectomy of the soft palate was performed, and the clinical signs improved, but only temporarily. A CT scan was performed, finding moderately leftward deviated nasal septum and severe periodontal disease. A dental procedure was performed, and the dog was treated with azithromycin and meloxicam for up to three weeks. The signs began to recur after four years, together with cyanosis (bluish discoloration of the skin due to low oxygen levels in the blood). At that time, dynamic laryngeal collapse was identified, and the dog underwent partial laryngectomy by cuneiformectomy (removal of the collapsed laryngeal cartilages). Ondansetron also was prescribed but without success. Clinical signs continued each night, and another CT scan showed a static nasal septum deviation with a thickened soft palate. So, a folded flap palatoplasty of the palate was performed. The dog's condition continued to worsen during nights. Next a permanent (crico)tracheostomy (PT) was performed. This is a surgical procedure in which cartilage consisting of tracheal rings are removed. For 3+ years following that PT surgery, the dog's owners reported that it was having a good quality of life with continued improvement in its nightly sleeping.

See, also, our discussion of stenotic nares.

RETURN TO TOP

• Snoring

Snoring is not normal for dogs, particularly loud snoring. It is a

symptom of sleep disordered breathing (SBD) caused by an obstruction. Snoring

can interfere with the dog breathing, and it has been

associated with oxygen deprivation (desaturation).

Snoring is caused by the vibration of soft tissue during sleep, usually

due to partial obstruction of the upper airway, such as

pharyngeal narrowing.

Snoring is not normal for dogs, particularly loud snoring. It is a

symptom of sleep disordered breathing (SBD) caused by an obstruction. Snoring

can interfere with the dog breathing, and it has been

associated with oxygen deprivation (desaturation).

Snoring is caused by the vibration of soft tissue during sleep, usually

due to partial obstruction of the upper airway, such as

pharyngeal narrowing.

In a November 2018 case study of five cavalier King Charles spaniels, they attributed "intranasal abnormalities" as the cause of snoring in all of the dogs, including severe nasal septal deviation, aberrant nasal turbinates, and soft palate elongation and thickening.

SDB at night can affect the dog's behaviors during the daytime, including excessive sleepyness (hypersomnolence) and sluggishness. See this June 2020 article in which cavaliers are singled out as being most commonly affected by loud snoring during sleep as evidence of SDB. Increased frequency or loudness of snoring should be noted and taken into account when investigating possible airway disorders.

In

a

May 2023 article, a team of Finnish researchers evaluated the use of a portable neckband manufactured by

Nukute Ltd. for detecting sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in 12

brachycephalic dogs (BDs), including 9

French bulldogs and a cavalier

King Charles spaniel. The other dogs were one each of an English bulldog

and a bullmastiff. A control group of 12 non-brachycephalic dogs were

included in the study, which lasted only one night for each dog at its

home. The neckband system reportedly is capable of measuring the

obstructive respiratory event index (OREI), which summarizes the rate of

obstructive SDB events per hour. The investigators report finding that

the BDs had a significantly higher OREI value and snore percentage than

the control dogs. They opined that the results would potentially be

different if the BD group consisted of more dogs with longer snouts such

as the bullmastiff and the cavalier. They found that the neckband system

was easy to use. They concluded that brachycephaly is associated with

SDB, and that the neckband system is a feasible way of characterizing

SDB in dogs.

French bulldogs and a cavalier

King Charles spaniel. The other dogs were one each of an English bulldog

and a bullmastiff. A control group of 12 non-brachycephalic dogs were

included in the study, which lasted only one night for each dog at its

home. The neckband system reportedly is capable of measuring the

obstructive respiratory event index (OREI), which summarizes the rate of

obstructive SDB events per hour. The investigators report finding that

the BDs had a significantly higher OREI value and snore percentage than

the control dogs. They opined that the results would potentially be

different if the BD group consisted of more dogs with longer snouts such

as the bullmastiff and the cavalier. They found that the neckband system

was easy to use. They concluded that brachycephaly is associated with

SDB, and that the neckband system is a feasible way of characterizing

SDB in dogs.

RETURN TO TOP

Other Disorders

Less common BAOS disoders include gastroesophageal reflux and the development of growths in the larynx, in response to the passage of gastroesophageal reflux, negative pressure, and other traumas casued by BAOS conditions.

Laryngeal Mass

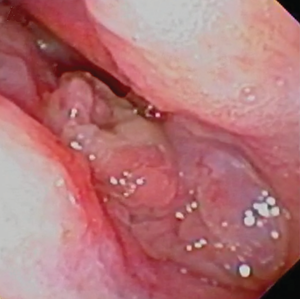

The larynx contains the two vocal chords, also called vocal folds,

which are flaps of tissue which vibrate in response to air passing

through the larynx, enabling the dog to make vocal sounds. The folds are

comprised of a ligament, a muscle, and a mucous membrane covering them.

In some BAOS dogs, including cavaliers but

particularly

French bulldogs, a mass of granulation tissue forms between the vocal

folds, in response to an ulceration caused by an airway malformation

condition. (See image at right.) The specific term to identify

this mass is "vocal fold granuloma", but the mass actually is not a

granuloma at all.

particularly

French bulldogs, a mass of granulation tissue forms between the vocal

folds, in response to an ulceration caused by an airway malformation

condition. (See image at right.) The specific term to identify

this mass is "vocal fold granuloma", but the mass actually is not a

granuloma at all.

In a March 2025 article, in which 13 BOAS-affected dogs, including 8 French bulldogs and 1 cavalier were studied, all of the patients exhibited inspiratory effort, indicating chronic upper airway negative pressure that exposed the vocal folds to chronic irritation and trauma to the vocal folds. The irritation was attributed at least in part to gastroesophageal reflux, another common condition in BAOS breeds. In this case, surgery was deemed necessary to remove the mass from between the folds, and to reduce the negative pressure and eliminate the injury to the vocal folds caused byt eh gastroesophageal reflux. The patients in this March 2025 report also were treated with corticosteroids and antibiotics. The cavalier and 11 of the other dogs were successfully treated. The other dog had a recurrance of the mass and required a second surgerial removal.

RETURN TO TOP

Breeders' Responsibilities

BAOS is a consequence of the conformation standards for the CKCS. Cavaliers with significant breathing difficulties or that have required surgery to correct airway obstruction, should not be used for breeding.

In

February 2023,

the OFA (Orthopedic Foundation of America)

joined the UK Kennel Club in examining dogs for symptoms of BOAS

(brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome). The examination, called

the Respiratory Function Grading Scheme, grades dogs on a scale from

Grade 0 to Grade III to objectively diagnose BOAS:

In

February 2023,

the OFA (Orthopedic Foundation of America)

joined the UK Kennel Club in examining dogs for symptoms of BOAS

(brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome). The examination, called

the Respiratory Function Grading Scheme, grades dogs on a scale from

Grade 0 to Grade III to objectively diagnose BOAS:

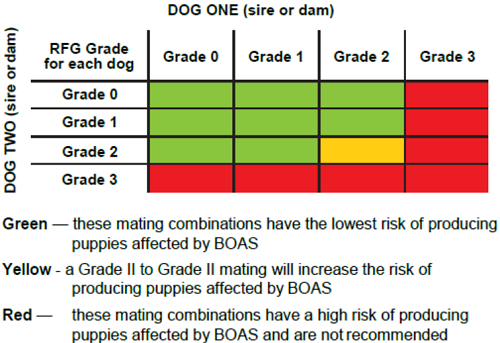

• Grade 0 - the dog is clinically unaffected and free of any respiratory signs of BOAS (no evidence of disease, no BOAS related noise heard even with a stethoscope)

• Grade I - the dog is clinically unaffected but does have mild respiratory signs linked to BOAS (noise is mild and only audible with a stethoscope)

• Grade II - the dog is clinically affected and has moderate respiratory signs of BOAS (noise is audible even without a stethoscope)

• Grade III - the dog is clinically affected and has severe respiratory signs of BOAS (noise is audible even without a stethoscope)

Both Grade 0 and Grade I will be considered to be clinically normal and BOAS-unaffected as they exercise without difficulty and do not appear to have any clinical signs related to airway obstruction. These will receive OFA certification numbers, and their results will be posted on the OFA website. In Grades 2 and 3, when stertor or stridor noise is heard without a stethoscope, these dogs are considered BOAS-affected with clinical signs affecting quality of life. Results for dogs with Grade 2 or 3 results will only be posted on the OFA website if their owners authorize release of abnormal data. All results will be shared with an international team of collaborators for statistical purposes, but individual abnormal results will never be publicly released unless specifically authorized. For additional details, see the OFA announcement.

Using the RFGS grades and the guidelines in the chart below, breeders may reduce the chances of producing puppies affected by BOAS. However, since the inheritance of BOAS is not fully understood and is not entirely predictable, this guidance cannot guarantee that all puppies from unaffected parents will be free of BOAS.

RETURN TO TOP

Research News

December 2024:

Cavalier with sleep disordered breathing endures three major

surgeries to cure it.

In a

December 2024 article,

Drs. Jessica M. Hynes, Jenna V. Menard, Daniel J. Lopez (right) report

on the case studies of three dogs diagnosed with sleep disordered

breathing, including apnea, one dog of which was a cavalier King Charles

spaniel. The

4-year-old cavalier diagnosed with SDB had these symptoms:

In a

December 2024 article,

Drs. Jessica M. Hynes, Jenna V. Menard, Daniel J. Lopez (right) report

on the case studies of three dogs diagnosed with sleep disordered

breathing, including apnea, one dog of which was a cavalier King Charles

spaniel. The

4-year-old cavalier diagnosed with SDB had these symptoms:

"The dog exhibited apneic episodes during sleep, followed by abrupt waking, gasping, disorientation, and screaming. These episodes occurred exclusively in the evening around once a night, and the patient was otherwise normal during the day."

Initially, the CKCS was treated with zonisamide for seizures, without success. Then, it was found to have a mildly elongated soft palate and no evidence of laryngeal collapse. A staphylectomy of the soft palate was performed, and the clinical signs improved, but only temporarily. A CT scan was performed, finding moderately leftward deviated nasal septum and severe periodontal disease. A dental procedure was performed, and the dog was treated with azithromycin and meloxicam for up to three weeks. The signs began to recur after four years, together with cyanosis (bluish discoloration of the skin due to low oxygen levels in the blood). At that time, dynamic laryngeal collapse was identified, and the dog underwent partial laryngectomy by cuneiformectomy (removal of the collapsed laryngeal cartilages). Ondansetron also was prescribed but without success. Clinical signs continued each night, and another CT scan showed a static nasal septum deviation with a thickened soft palate. So, a folded flap palatoplasty of the palate was performed. The dog's condition continued to worsen during nights. Next a permanent (crico)tracheostomy (PT) was performed. This is a surgical procedure in which cartilage consisting of tracheal rings are removed. For 3+ years following that PT surgery, the dog's owners reported that it was having a good quality of life with continued improvement in its nightly sleeping.

February 2024:

Finnish study finds cavaliers rank high among breeds at risk for

sleep-disorderd breathing.

In

a

February 2024 article, a team of Finnish researchers (Iida

Niinikoski [right], Sari-Leena Himanen, Mirja Tenhunen, Mimma

Aromaa, Liisa Lilja-Maula, Minna M. Rajamäki) evaluated the risk factors

for sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in serveral dog breeds. Of 28

brachycephalic dogs, 8 (28.5%) were cavalier King Charles spaniels.

Other SDB breeds comprised 35 dogs. They reported that "We had an

overrepresentation of Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, French Bulldogs

and Labrador Retrievers." They found that brachycephaly was a

significant risk factor for SDB, particularly apnea, and BOAS-positive

class (moderate or severe BOAS signs) was a significant risk factor,

along with excess weight. Aging and Chiari-like malformation were not

risk factors among the dogs in this study.

In

a

February 2024 article, a team of Finnish researchers (Iida

Niinikoski [right], Sari-Leena Himanen, Mirja Tenhunen, Mimma

Aromaa, Liisa Lilja-Maula, Minna M. Rajamäki) evaluated the risk factors

for sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in serveral dog breeds. Of 28

brachycephalic dogs, 8 (28.5%) were cavalier King Charles spaniels.

Other SDB breeds comprised 35 dogs. They reported that "We had an

overrepresentation of Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, French Bulldogs

and Labrador Retrievers." They found that brachycephaly was a

significant risk factor for SDB, particularly apnea, and BOAS-positive

class (moderate or severe BOAS signs) was a significant risk factor,

along with excess weight. Aging and Chiari-like malformation were not

risk factors among the dogs in this study.

June 2023:

Swedish study of 327 breeds finds cavaliers rank in top

five of high risk breeds for brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome

disorders.

In a

May 2023 article, Swedish researchers M. Dimopoulou

(right), K.

Engdah, J. Ladlow, G. Andersson, Å. Hedhammar, E. Skiöldebrand, and I.

Ljungvall examined the medical records from 2011 through 2014 of 450,000

dogs of 327 breeds, for upper respiratory tract disorders (URTs). They

included calculatations of the breed-specific incidence rate for each

breed. Their findings include:

In a

May 2023 article, Swedish researchers M. Dimopoulou

(right), K.

Engdah, J. Ladlow, G. Andersson, Å. Hedhammar, E. Skiöldebrand, and I.

Ljungvall examined the medical records from 2011 through 2014 of 450,000

dogs of 327 breeds, for upper respiratory tract disorders (URTs). They

included calculatations of the breed-specific incidence rate for each

breed. Their findings include:

• "The Boston terrier, boxer, CKCS [cavalier King Charles spaniel], English and French bulldog and pug are brachycephalic breeds and affected to a variable degree by BOAS [brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome]."

• "Among 13 breeds with high RR [relative risk] for URT disorders in this study, eight (Boston terrier, boxer, CKCS, English bulldog, French bulldog, Japanese chin, Pomeranian, pug) are recognised as brachycephalic by most researchers."

• "The brachycephalic conformation has been linked to an increased risk for URT disorders, and specifically BOAS, in the French and English bulldog, the CKCS, Boston terrier and the pug."

• "The Chihuahua, CKCS, Pomeranian and Yorkshire terrier are breeds frequently affected with the URT disorder tracheal collapse."

• "The boxer, CKCS, Chihuahua, French bulldog, pug and standard poodle had high risk for co-morbidity both prior and after the first URT claim."

May 2023:

Finnish researchers use electronic neckband to track

sleep-disordered breathing in brachycephalic dogs.

In

a

May 2023 article, a team of Finnish researchers (Iida Niinikoski,

Sari-Leena Himanen, Mirja Tenhunen, Liisa Lilja-Maula, Minna M.

Rajamäki) evaluated the use of a portable neckband manufactured by

Nukute Ltd. for detecting sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in 12

brachycephalic dogs (BDs), including 9 French bulldogs and a cavalier

King Charles spaniel. The other dogs were one each of an English bulldog

and a bullmastiff. A control group of 12 non-brachycephalic dogs were

included in the study, which lasted only one night for each dog at its

home. The neckband system reportedly is capable of measuring the

obstructive respiratory event index (OREI), which summarizes the rate of

obstructive SDB events per hour. The investigators report finding that

the BDs had a significantly higher OREI value and snore percentage than

the control dogs. They opined that the results would potentially be

different if the BD group consisted of more dogs with longer snouts such

as the bullmastiff and the cavalier. They found that the neckband system

was easy to use. They concluded that brachycephaly is associated with

SDB, and that the neckband system is a feasible way of characterizing

SDB in dogs.

In

a

May 2023 article, a team of Finnish researchers (Iida Niinikoski,

Sari-Leena Himanen, Mirja Tenhunen, Liisa Lilja-Maula, Minna M.

Rajamäki) evaluated the use of a portable neckband manufactured by

Nukute Ltd. for detecting sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in 12

brachycephalic dogs (BDs), including 9 French bulldogs and a cavalier

King Charles spaniel. The other dogs were one each of an English bulldog

and a bullmastiff. A control group of 12 non-brachycephalic dogs were

included in the study, which lasted only one night for each dog at its

home. The neckband system reportedly is capable of measuring the

obstructive respiratory event index (OREI), which summarizes the rate of

obstructive SDB events per hour. The investigators report finding that

the BDs had a significantly higher OREI value and snore percentage than

the control dogs. They opined that the results would potentially be

different if the BD group consisted of more dogs with longer snouts such

as the bullmastiff and the cavalier. They found that the neckband system

was easy to use. They concluded that brachycephaly is associated with

SDB, and that the neckband system is a feasible way of characterizing

SDB in dogs.

April 2023:

Brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS) affected left

atrium parameters independent of mitral valve disease, in a Slovenia

study.

In a

February 2023 article, Slovenian researchers (M. Brložnik, A. Nemec

Svete, V. Erjavec & A. Domanjko Petric [right]) compared the echocardiographic

measurements in three brachycephalic dog breeds -- 30 French bulldogs,

15 pugs, and 12 Boston terriers -- having signs of brachycephalic

obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS), to determine possible

echocardiographic differences between brachycephalic and

non-brachycephalic dogs and to evaluate possible echocardiographic

changes due to BOAS. There obtained several echocardiographic

measurements, including the left artium-to-aorta ratio (LA/Ao). They

report finding that the LA/Ao values for the French bulldogs were 1.56

(1.44-1.60), and for pugs were 1.49 (1.45-1.62), and for Boston terriers

were 1.55 (1.50-1.68). They found that for all three breeds, dogs with

signs of BAOS had different parameters than did dogs of the same breed

without BAOS, as well as significant differences in echocardiographic

parameters between the dogs of the three brachycephalic breeds and

non-brachycephalic dogs. They concluded:

In a

February 2023 article, Slovenian researchers (M. Brložnik, A. Nemec

Svete, V. Erjavec & A. Domanjko Petric [right]) compared the echocardiographic

measurements in three brachycephalic dog breeds -- 30 French bulldogs,

15 pugs, and 12 Boston terriers -- having signs of brachycephalic

obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS), to determine possible

echocardiographic differences between brachycephalic and

non-brachycephalic dogs and to evaluate possible echocardiographic

changes due to BOAS. There obtained several echocardiographic

measurements, including the left artium-to-aorta ratio (LA/Ao). They

report finding that the LA/Ao values for the French bulldogs were 1.56

(1.44-1.60), and for pugs were 1.49 (1.45-1.62), and for Boston terriers

were 1.55 (1.50-1.68). They found that for all three breeds, dogs with

signs of BAOS had different parameters than did dogs of the same breed

without BAOS, as well as significant differences in echocardiographic

parameters between the dogs of the three brachycephalic breeds and

non-brachycephalic dogs. They concluded:

"We found significant differences in echocardiographic parameters between dogs of the three brachycephalic breeds and non-brachycephalic dogs, implying that breed-specific echocardiographic reference values should be used in clinical practice. In addition, significant differences were observed between brachycephalic dogs with and without signs of BOAS. The observed echocardiographic differences suggest higher right heart diastolic pressures affecting right heart function in brachycephalic dogs with and without signs of BOAS, and several of the differences are consistent with findings in OSA patients. Most of the changes of the heart morphology and function can be attributed to brachycephaly alone and not to the symptomatic stage."

EDITOR'S

NOTE: We find from this study that dogs with BAOS can have

changes in their hearts' measurements and functions due not to

mitral valve disease (MVD) at all, but due to the BAOS. This means

that cardiologists cannot continue to rely upon simplistic species-wide

echocardiographic measurements to diagnose the presence of heart

enlargement, or even the existence of MVD at all, in brachycephalic dogs

if they have symptoms of BAOS. Cardiologists now are faced with a new

learning curve.

EDITOR'S

NOTE: We find from this study that dogs with BAOS can have

changes in their hearts' measurements and functions due not to

mitral valve disease (MVD) at all, but due to the BAOS. This means

that cardiologists cannot continue to rely upon simplistic species-wide

echocardiographic measurements to diagnose the presence of heart

enlargement, or even the existence of MVD at all, in brachycephalic dogs

if they have symptoms of BAOS. Cardiologists now are faced with a new

learning curve.

February 2023:

OFA announces the Respiratory Function Grading Scheme testing

for BOAS. OFA (Orthopedic Foundation of America) has

joined the UK Kennel Club in examining dogs for symptoms of BOAS

(brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome). The examination, called

the Respiratory Function Grading Scheme, grades dogs on a scale from

Grade 0 to Grade III to objectively diagnose BOAS:

February 2023:

OFA announces the Respiratory Function Grading Scheme testing

for BOAS. OFA (Orthopedic Foundation of America) has

joined the UK Kennel Club in examining dogs for symptoms of BOAS

(brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome). The examination, called

the Respiratory Function Grading Scheme, grades dogs on a scale from

Grade 0 to Grade III to objectively diagnose BOAS:

• Grade 0 - the dog is clinically unaffected and free of any respiratory signs of BOAS (no evidence of disease, no BOAS related noise heard even with a stethoscope)

• Grade I - the dog is clinically unaffected but does have mild respiratory signs linked to BOAS (noise is mild and only audible with a stethoscope)

• Grade II - the dog is clinically affected and has moderate respiratory signs of BOAS (noise is audible even without a stethoscope)

• Grade III - the dog is clinically affected and has severe respiratory signs of BOAS (noise is audible even without a stethoscope)

Both Grades 0 and I will be considered to be clinically normal and BOAS-unaffected as they exercise without difficulty and do not appear to have any clinical signs related to airway obstruction. These will receive OFA certification numbers, and their results will be posted on the OFA website. In Grades 2 and 3, when stertor or stridor noise is heard without a stethoscope, these dogs are considered BOAS-affected with clinical signs affecting quality of life. Results for dogs with Grade 2 or 3 results will only be posted on the OFA website if their owners authorize release of abnormal data. All results will be shared with an international team of collaborators for statistical purposes, but individual abnormal results will never be publicly released unless specifically authorized. For additional details, see the OFA announcement.

April 2021:

Cavalier with sleep disordered breathing (SDB) is successfully

fitted with a ventilation mask every night.

In an

April 2021 article, a team of Australian veterinary specialists

(Waylon Wiseman [right], A. Rosenblatt, M. Kunga)

report a case of a 4-year-old female cavalier King Charles spaniel

experiencing sleep apnea episodes every 10 to 15 minutes during sleep.

They diagnosed "dynamic pharyngeal collapse" (DPC), which involves

partial or complete collapse of the pharynx. They performed a series of

surgical procedures -- bilateral tonsillectomy, bilateral laryngeal

sacculectomy, and unilateral cricoarytenoid lateralisation -- with

minimal improvement. The cavalier's breathing pattern quality improved

while awake, but she continued to suffer from SBD at night, with apnea

episodes every 30 minutes. The dog was fitted with a "continuous

positive airway pressure" (CPAP) device, which included a mask connected

to an air hose and pump, to create a mild positive pressure in the dog's

airway. (See Figures 1 & 2.) A muzzle was fitted over the mask to secure

it to the dog's head. The cavalier gradually got accustomed to the

device, with the owner using positive reinforcement with treats and

removing the apparatus before the dog displayed signs of distress.

Eventually, after continuing to suffer SDB episodes without the device,

the dog sought out the mask and muzzle. With the CPAP device in place,

the cavalier was able to sleep between 4 to 5 hours each night. Four

years later, when the cavalier was 8 years old, she was examined with a

dynamic fluoroscope to determine if the SDB was due to DPC. The

fluoroscopy exam confirmed partial pharyngeal collapse.

In an

April 2021 article, a team of Australian veterinary specialists

(Waylon Wiseman [right], A. Rosenblatt, M. Kunga)

report a case of a 4-year-old female cavalier King Charles spaniel

experiencing sleep apnea episodes every 10 to 15 minutes during sleep.

They diagnosed "dynamic pharyngeal collapse" (DPC), which involves

partial or complete collapse of the pharynx. They performed a series of

surgical procedures -- bilateral tonsillectomy, bilateral laryngeal

sacculectomy, and unilateral cricoarytenoid lateralisation -- with

minimal improvement. The cavalier's breathing pattern quality improved

while awake, but she continued to suffer from SBD at night, with apnea

episodes every 30 minutes. The dog was fitted with a "continuous

positive airway pressure" (CPAP) device, which included a mask connected

to an air hose and pump, to create a mild positive pressure in the dog's

airway. (See Figures 1 & 2.) A muzzle was fitted over the mask to secure

it to the dog's head. The cavalier gradually got accustomed to the

device, with the owner using positive reinforcement with treats and

removing the apparatus before the dog displayed signs of distress.

Eventually, after continuing to suffer SDB episodes without the device,

the dog sought out the mask and muzzle. With the CPAP device in place,

the cavalier was able to sleep between 4 to 5 hours each night. Four

years later, when the cavalier was 8 years old, she was examined with a

dynamic fluoroscope to determine if the SDB was due to DPC. The

fluoroscopy exam confirmed partial pharyngeal collapse.

February 2021:

Drs. Rusbridge and Knowler find impaired cerebrospinal fluid

circulation predisposes Chiari-like malformation and syringomyelia in

cavaliers.

In

a

February 2021 article, neurology researchers Clare Rusbridge and

Penny Knowler [right] review current data linking cerebrospinal

fluid (CSF) disorders with brachyephaly and shorten muzzles in cavalier

King Charles spaniels and other small breed dogs. They point out that

there is increasing evidence that brachycephaly disrupts CSF movement

and absorption, predisposing ventriculomegaly, hydrocephalus, and

quadrigeminal cistern expansion, as well as Chiari-like malformation and

syringomyelia. They show how the reduction of the lymphatic absorption

of CSF through the lymphatic system organs located in the nasal and

skull base, combined with the restriction of CSF movement through the

junction of the skull with the spinal cord, appear to be key

consequences of extreme brachycephaly in dogs and explain the likely

causes of these neurological disorders..

In

a

February 2021 article, neurology researchers Clare Rusbridge and

Penny Knowler [right] review current data linking cerebrospinal

fluid (CSF) disorders with brachyephaly and shorten muzzles in cavalier

King Charles spaniels and other small breed dogs. They point out that

there is increasing evidence that brachycephaly disrupts CSF movement

and absorption, predisposing ventriculomegaly, hydrocephalus, and

quadrigeminal cistern expansion, as well as Chiari-like malformation and

syringomyelia. They show how the reduction of the lymphatic absorption

of CSF through the lymphatic system organs located in the nasal and

skull base, combined with the restriction of CSF movement through the

junction of the skull with the spinal cord, appear to be key

consequences of extreme brachycephaly in dogs and explain the likely

causes of these neurological disorders..

October 2020:

Cavaliers ranked third among brachycephalic breeds requiring

veterinary care in the UK in 2016.

In an

October 2020 article by a team of Royal Veterinary College

researchers (D. G. O'Neill [right], C. Pegram, P. Crocker, D.

C. Brodbelt, D. B. Church, R. M. A. Packer), they examined the 2016

primary-care veterinary records of a random sample of 22,333 dogs to

identify predispositions and protections in brachycephalic dogs. Of

those dogs, 4,169 (18.74%) were of brachycephalic breeds and the

remaining 18,079 (81.26%) were non-brachycephalic. The most common

brachycephalic breeds were Chihuahuas (955 dogs, 22.91%), Shih-tzus (795

dogs, 19.07%) and cavalier King Charles spaniels (435 dogs, 10.43%). The

most common disorders (i.e. greatest prevalence) which they found in the

brachycephalic types were periodontal disease, otitis externa, obesity,

anal sac impaction, overgrown nail(s), diarrhea, and heart murmur. Two

disorders which had reduced odds for brachycephalic types were

undesirable behavior and claw injury. Regarding the CKCS specifically,

they report that:

In an

October 2020 article by a team of Royal Veterinary College

researchers (D. G. O'Neill [right], C. Pegram, P. Crocker, D.

C. Brodbelt, D. B. Church, R. M. A. Packer), they examined the 2016

primary-care veterinary records of a random sample of 22,333 dogs to

identify predispositions and protections in brachycephalic dogs. Of

those dogs, 4,169 (18.74%) were of brachycephalic breeds and the

remaining 18,079 (81.26%) were non-brachycephalic. The most common

brachycephalic breeds were Chihuahuas (955 dogs, 22.91%), Shih-tzus (795

dogs, 19.07%) and cavalier King Charles spaniels (435 dogs, 10.43%). The

most common disorders (i.e. greatest prevalence) which they found in the

brachycephalic types were periodontal disease, otitis externa, obesity,

anal sac impaction, overgrown nail(s), diarrhea, and heart murmur. Two

disorders which had reduced odds for brachycephalic types were

undesirable behavior and claw injury. Regarding the CKCS specifically,

they report that:

"The degree (or severity) of brachycephaly varies between breeds (a bulldog may be considered as more severely brachycephalic than a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel) but there can also be considerable variation in brachycephaly within breeds. Shifting the median severity of brachycephaly towards a longer skull shape within breeds has been suggested as one option to reduce the prevalence of disorders directly linked to brachycephaly while still retaining these breeds within the overall dog population."

They concluded that:

"This study provides strong evidence to support the common assertion that brachycephalic breeds are generally less healthy than their non-brachycephalic counterparts in relation to total disorder counts and specific common conditions recorded. Potential solutions to some of these health problems are likely to require conformational change to current skull shapes averages for many breeds; however, many other health problems will require targeted action at the individual breed level, owing to large differences in individual breed predispositions to disorders."

May 2020:

German study of cavalier nasal passages shows rapid elongation

of facial shape has created the breed's complex nasal skeleton.

In

a

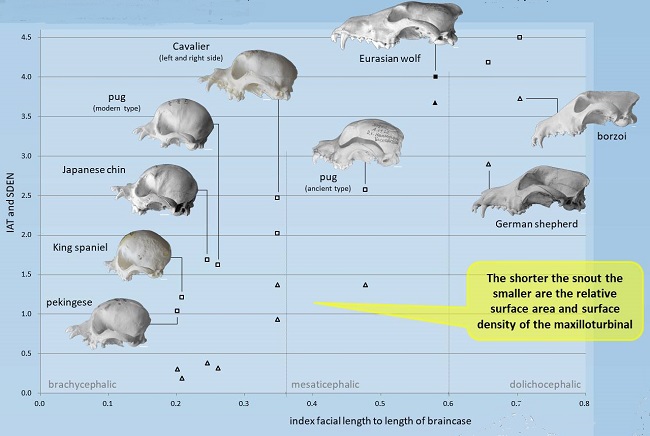

May 2020 article, two mammalogists, Franziska Wagner and Irina Ruf

(right), have examined the skulls of five toy dog breeds

(Japanese chin, King Charles spaniel, cavalier King Charles spaniel,

pekingese, and pug), to compare the consequences of breeders'

intentional genetic mutations upon the nasal structures -- particularly

the turbinates (air-filters) of the resulting generations of the breeds.

The investigators found that because the cavalier has resulted from a

relatively rapid (since the year 1928) elongation of its snout from its

King Charles spaniel ancestor (called "reverse breeding"), its turbinal

skeleton has changed very little from that of its ancestors. As for

other breeds, they found that with decreasing snout length, the nasal

cavity is minimized and the seven turbinals suffer as a consequence,

especially the interturbinals, which are reduced in number during their

developmental period.

In

a

May 2020 article, two mammalogists, Franziska Wagner and Irina Ruf

(right), have examined the skulls of five toy dog breeds

(Japanese chin, King Charles spaniel, cavalier King Charles spaniel,

pekingese, and pug), to compare the consequences of breeders'

intentional genetic mutations upon the nasal structures -- particularly

the turbinates (air-filters) of the resulting generations of the breeds.

The investigators found that because the cavalier has resulted from a

relatively rapid (since the year 1928) elongation of its snout from its

King Charles spaniel ancestor (called "reverse breeding"), its turbinal

skeleton has changed very little from that of its ancestors. As for

other breeds, they found that with decreasing snout length, the nasal

cavity is minimized and the seven turbinals suffer as a consequence,

especially the interturbinals, which are reduced in number during their

developmental period.

February 2020:

Australian study finds cavaliers ranked as second highest breed

for brachycephalic airway surgeries.

In

a

February 2020 article, researchers (Barbara Lindsay [right],