Artery Thrombosis & Thromboembolism

in Cavalier King Charles

Spaniels

-

What It Is

What It Is - Symptoms

- Diagnosis

- Related Disorders

- Treatment

- Research News

- Related Links

- Veterinary Resources

Cavalier King Charles spaniels appear to have a genetic disposition to blood clots, called a thrombus or thrombi, in certain of their main arteries -- the aortic, pulmonary, and femoral arteries. In a 2022 textbook, the cardiologists-authors stated that:

"Primary vascular disease as an underlying cause is suggested in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels by a genetic predisposition to femoral artery and pulmonary artery (PA) thrombosis."

Cavaliers also appear predisposed to develop cerebellar infarcts -- a sudden blockage of the blood flow to an area of the cerebellum of the brain caused either by a blood clot or by the rupture of one of the cerebellar arteries. See our Cerebellar Infarcts - Strokes webpage for the details.

What It Is

“Thrombus” is the medical name for a blood clot, and “thrombosis” is the event which occurs when a clot develops inside of a blood vessel and remains in place and either reduces or blocks the flow of blood through that vessel. “Embolus” is a particle from a blood clot, which has traveled through the blood vessel, and “thromboembolism” occurs when the traveling particle reduces the flow of blood.

Aorta

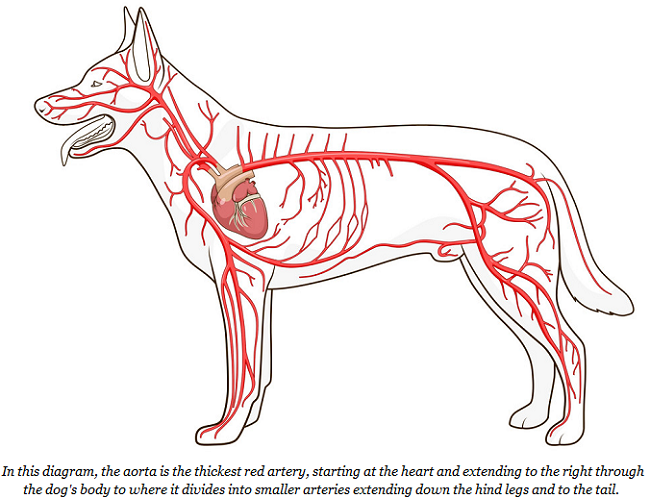

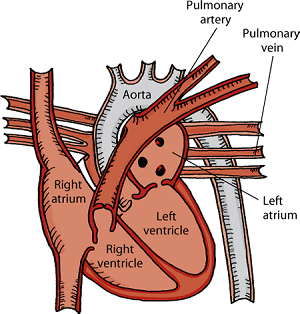

Aortic thrombosis (ATh) and aortic thromboembolism (ATE) involve blood clots in the dogs' aortic artery. The aorta is the main artery in the dog's body. It starts at the left ventricle of the heart and extends down to the abdomen, where it splits into smaller arteries. (See diagram below.)

Both aortic thrombosis and aortic thromboembolism are known to develop in dogs, but are relatively uncommon in nearly all breeds. However, the cavalier King Charles spaniel has been found to be predisposed to both conditions. See these cases discussed below: March 2000, June 2005, April 2008, February 2011, and January 2017.

In a December 2023 article, Royal Veterinary College (RVC) researchers studied the risk for thrombotic disease (TD) among dogs with renal proteinuria -- high levels of protein in urine indicating kidney damage or disease. They found 150 dogs with renal proteinuria over a period from 2004 to 2021 in their database. Of those, 50 also had TD. Five of those 50 dogs were cavaliers (10%), which indicated that CKCSs had higher rates of TD among all breeds diagnosed with renal proteinuria. All five cavaliers had blood clots in their arteries -- arterial thrombosis (AT) -- four of which were in the aorta. They suggested, without evidence but based upon prior published studies, that:

"Reasons suggested for a genetic predisposition of CKCS for TD include a connective tissue disorder, a subset of the breed having increased platelet reactivity, and their increased incidence of cardiac disease. MMVD [myxomatous mitral valve disease] was present in 4 out of 5 of the CKCS with TD and was a common comorbidity in dogs of other breeds with TD in this study; however, ... MMVD is not considered a risk factor for TD."

RETURN TO TOP

Pulmonary

arteries

Pulmonary

arteries

The pulmonary trunk is the main pulmonary artery. It begins at the heart and then divides into the right and left pulmonary arteries, which carry blood into the two lobes of the lungs. Pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) occurs when a blood clot lodges in one of those pulmonary arteries.

Pulmonary thrombosis was first reported in the CKCS in an August 2ooo article in which seven cavaliers were diagnosed with cases of PTE, all aged between eight and nine years.

RETURN TO TOP

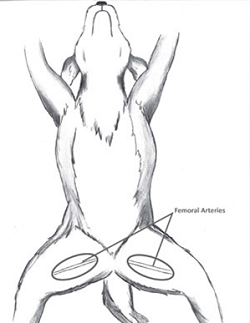

Femoral arteries

The two femoral arteries extend down the dog's hind legs. Blood clots

in those arteries also are known as femoral artery occlusions. Such a

clot leads to the interruption of blood flow to tissues served by that

portion of the blood vessel. This appears to be

a disorder unique to the cavalier King Charles spaniel, but

fortunately, it usually is of no clinical importance because dogs have

adequate collateral circulation in their hind legs. This evidence

indicates the CKCS may have a genetic predisposition to this disorder

and probable weakness in the femoral artery wall.

The two femoral arteries extend down the dog's hind legs. Blood clots

in those arteries also are known as femoral artery occlusions. Such a

clot leads to the interruption of blood flow to tissues served by that

portion of the blood vessel. This appears to be

a disorder unique to the cavalier King Charles spaniel, but

fortunately, it usually is of no clinical importance because dogs have

adequate collateral circulation in their hind legs. This evidence

indicates the CKCS may have a genetic predisposition to this disorder

and probable weakness in the femoral artery wall.

In an October 1997 article, cardioloigsts studied the femoral arteries of 954 cavaliers. They found that 22 of the dogs (2.3%) had an undetectable right or left femoral pulse, and that 40 other dogs (4.2%) had weak femoral pulses. They also found thickening of the femoral walls and a thrombus in one dog in which they exmained serial sections of its occluded artery. The researchers concluded that:

"Femoral artery occlusion is rare in other breeds and is not clinically important in dogs because of adequate collateral circulation; however, its rather common development in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels indicates a genetic predisposition and probable weakness in the femoral artery wall."

In an April 2004 article, Danish cardiologists found in a study of 109 cavaliers that:

"... a weak femoral [hind leg] artery pulse is a common finding in CKCS and Dachshunds, and that the pulse strength in any one dog is reasonably reproducible. Pulse strength was found to be inversely related to heart rate, degree of obesity and MVP [mitral valve prolapse] severity. In addition, femoral artery pulse strength decreased with age. The weak femoral artery pulses appear to reflect a decrease in diastolic artery diameter and/or systolic distension associated with a local decrease in blood flow, not artery occlusion or changes in pulse pressure and stroke volume."

RETURN TO TOP

Symptoms

Due to the wide variety of disorders concurrent with blood clots in these arteries, the clinical signs of these diseases also vary widely. Regardless of the symptoms, dogs with the most sudden and severe onset (acute) of signs tend to have shorter survival times and need to be diagnosed and treated immediately. Dogs with slower onsets (chronic) tend to be exercise-intolearant and have longer survival times.

Symptoms of ATh and ATE include:

Symptoms of ATh and ATE include:

• paleness

• pain

• weak pulse

• partial paralysis

• imbalance

• exercise intolerance

• hind limb weakness or stiffness

• neurological signs.

Hind limb weakness is attributed to the fact that the aorta ends where it divides into a set of lesser arteries (the iliacs) and then to the femorals, extending down each hind leg and the tail. The blood clot often is found at that intersection where the aorta ends, interfering with the blood flow to the legs (the aortic trifurcation). (The diagram at right is a view looking down from above over a standing dog, showing the aorta at the top, and where it connects to the external iliac arteries which extend outward and down the hind legs, beyond which the aorta connects to the thinner internal iliac arteries which also extend down the hind legs, and at the bottom is the thinnest, the median sacral artery which extends to the dog's tail.)

RETURN TO TOP

Diagnosis

In addition to observing the patients' behaviors and signs, the absence of, or decreased femoral pulses is a usual finding in most all cases. Decreased spinal reflexes, decreased of absent patellar (knee) reflexes, and general pelvic and hind limb weakness are usual indications.

Blood tests, including CBC, serum biochemistry, and blood glucose

concentrations in the hindlimbs, should be conducted. A thorough

neurolognical evaluation should be performed. Urinalysis and untrasound

scans of the

abdomen are called for. Blood flow through and around the

thrombus can also be evaluated using Doppler

ultrasound. Magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) and/or computed tomography (CT) are less

frequently used in diagnosis but may be useful when different sites of

thrombus formations or thromboembolism are suspected. Chest -rays may

identify underlying causes for ATh but will not lead to a definitive

diagnosis in most cases.

ultrasound. Magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) and/or computed tomography (CT) are less

frequently used in diagnosis but may be useful when different sites of

thrombus formations or thromboembolism are suspected. Chest -rays may

identify underlying causes for ATh but will not lead to a definitive

diagnosis in most cases.

It is important for the examining veterinarians to consider artery thrombosis as a differential diagnoses in dogs with an acute onset of pelvic limb neurological deficits, as well as in dogs with exercise intolerance. In a February 2011 article, French veterinary specialists reported the diagnosis and treatment of a female cavalier King Charles spaniel (see above photo) which had sudden lameness in her right hind leg. The examination showed a weak femoral pulse, indicating possible aortic or iliac or femoral thromboembolism. The dog also was diagnosed with a concurrent nephrotic syndrome. The authors concluded:

"A lameness or even a simple intolerance to effort are sufficient to suggest aortic thromboembolism, especially in a Cavalier King Charles."

RETURN TO TOP

Related Disorders

Artery thrombosis is associated with any of several other disorders, including protein losing nephropathy (PLN) due to liver disorders which is the most consistently diagnosed concurrent disease in dogs. Others include diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, Cushing’s Disease (hyperadrenocorticism or HAC), and immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (ITP).

Other disorders associated with artery thromboembolism likewise are varied. The most commonly found causes are heart diseases (especially cardiac arrhythmias and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), neoplasia (abnormal growths), protein losing nephropathy (PLN), Cushing’s Disease (hyperadrenocorticism or HAC), chronic urinary tract infections, chronic kidney disease (CKD), sepsis (inadequate body response to infection), and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AIHA).

Condtions of the cavalier which are similar to blood clots in the aorta but located elsewhere in the dog's body are clots in the brain (Cerebellar Infarcts).

RETURN TO TOP

Treatment

Initial medical treatment consists of dissolving the existing clot(s)

using drugs called thrombolytics, and attempting to

prevent the formation of any new clots. Treatment also usually is

directed to the suspected

underlying concurrent disorders associated

with the formation of the blood clots, and to ease any pain.

underlying concurrent disorders associated

with the formation of the blood clots, and to ease any pain.

Oral medications directed to dissolving or breaking up the clots include platelet inhibitors (usually acetylsalicylic acid -- aspirin) and anti-coagulants. Anti-coagulants include heparins (Dalteparin), warfarin (Coumadin, Jantoven), fondaparinux (Aroxtra), and rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Platelet P2Y12 ADP receptor antagonists include thienopyridine. Thrombin inhibitors include dabigatran (Pradaxa) and argatroban. Antiplatelet medications include clopidogrel (Plavix).

Intravenous thrombolyic therapy for dissolving the clots includes the

infusion of a tissue plasminogen activator (TPA)

including streptokinase (Streptase) and

alteplase (Activase,

Actilyse). TPA are naturally-occurring enzymes found in the

endothelial cells lining the blood vessels, which can convert the

chemical balance of the clots and aid in dissolving them. TPAs are not

always effective and can have

troublesome side effects in some dogs,

including bloody vomit.

troublesome side effects in some dogs,

including bloody vomit.

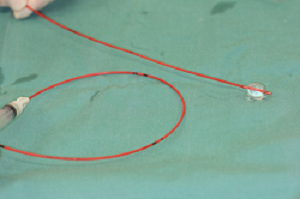

Surgical remedies are attempted rarely in dogs and include removal of the clot (thrombectomy) and opening the blocked or narrowed blood vessel to allow the blood to by-pass the clot. In a January 2018 article, German veterinary surgeons report successfully removing a thrombus (blood clot) from the aorta of an Australian shepherd dog, using a Fogarty Arterial Thrombectomy Catheter (see photo at right), during open artery surgery.

RETURN TO TOP

Research News

December 2023:

Cavaliers ranked first among 50 dogs with combined renal proteinuria and

blood clots in arteries.

In

a

December 2023 article, Royal Veterinary College (RVC) researchers

Luca Fortuna (right) and Harriet M. Syme studied the risk for

blood clots in blood vessels -- thrombotic disease (TD) -- among dogs

with renal proteinuria -- high levels of protein in urine indicating

kidney damage or disease. They found 150 dogs with renal proteinuria

over a period from 2004 to 2021 in their database. Of those, 50 also had

TD. Five of those 50 dogs were cavalier King Charles spaniels (10%),

which indicated that CKCSs had higher rates of TD among all breeds

diagnosed with renal proteinuria. All five cavaliers had blood clots in

their arteries -- arterial thrombosis (AT) -- four of which were in the

aorta. They suggested, without evidence but based upon prior published

studies, that:

In

a

December 2023 article, Royal Veterinary College (RVC) researchers

Luca Fortuna (right) and Harriet M. Syme studied the risk for

blood clots in blood vessels -- thrombotic disease (TD) -- among dogs

with renal proteinuria -- high levels of protein in urine indicating

kidney damage or disease. They found 150 dogs with renal proteinuria

over a period from 2004 to 2021 in their database. Of those, 50 also had

TD. Five of those 50 dogs were cavalier King Charles spaniels (10%),

which indicated that CKCSs had higher rates of TD among all breeds

diagnosed with renal proteinuria. All five cavaliers had blood clots in

their arteries -- arterial thrombosis (AT) -- four of which were in the

aorta. They suggested, without evidence but based upon prior published

studies, that:

"Reasons suggested for a genetic predisposition of CKCS for TD include a connective tissue disorder, a subset of the breed having increased platelet reactivity, and their increased incidence of cardiac disease. MMVD [myxomatous mitral valve disease] was present in 4 out of 5 of the CKCS with TD and was a common comorbidity in dogs of other breeds with TD in this study; however, ... MMVD is not considered a risk factor for TD."

January 2018:

German surgeons successfully remove aortic thrombus using a

Fogarty catheter.

In

a

January 2018 article, German veterinary surgeons (Maartje Schwede

[right], Olaf Richter, Michaele Alef, Tobias Theuß, Shenja

Loderstedt) report successfully

removing a thrombus (blood clot) from the aorta of an 8-year-old Australian

shepherd dog, using a Fogarty Arterial Thrombectomy Catheter, during

open artery surgery. They explained that the catheter was inserted in

both directions through the thrombus to the end of the aorta. The

catheter balloon was insufflated and the catheter pulled back. This

maneuver enabled the retraction of the thrombus. There was no adhesion

of the clot to the aortic wall The remaining small particles were

flushed out of the vessel with physiological sodium chloride solution.

The aorta was closed with a continuous suture and the abdomen according

to standard procedures.

In

a

January 2018 article, German veterinary surgeons (Maartje Schwede

[right], Olaf Richter, Michaele Alef, Tobias Theuß, Shenja

Loderstedt) report successfully

removing a thrombus (blood clot) from the aorta of an 8-year-old Australian

shepherd dog, using a Fogarty Arterial Thrombectomy Catheter, during

open artery surgery. They explained that the catheter was inserted in

both directions through the thrombus to the end of the aorta. The

catheter balloon was insufflated and the catheter pulled back. This

maneuver enabled the retraction of the thrombus. There was no adhesion

of the clot to the aortic wall The remaining small particles were

flushed out of the vessel with physiological sodium chloride solution.

The aorta was closed with a continuous suture and the abdomen according

to standard procedures.

February 2011:

French researchers conclude lameness or exercise intolerance in

cavaliers should suggest aortic thromboembolism.

In

a February 2011 article,

French veterinary specialists T. de Chalus and Christelle Maurey-Guenec

(right) reported the diagnosis and treatment of a female

cavalier King Charles spaniel which had sudden lameness in her right hind

leg. The examination showed a weak femoral pulse, indicating possible

aortic thromboembolism. The dog also was diagnosed with a concurrent

nephrotic syndrome. The dog was treated with acetylsalicylic acid and an

ACE-inhibitor, but after another thrombus appeared, it was euthanized.

The authors concluded:

In

a February 2011 article,

French veterinary specialists T. de Chalus and Christelle Maurey-Guenec

(right) reported the diagnosis and treatment of a female

cavalier King Charles spaniel which had sudden lameness in her right hind

leg. The examination showed a weak femoral pulse, indicating possible

aortic thromboembolism. The dog also was diagnosed with a concurrent

nephrotic syndrome. The dog was treated with acetylsalicylic acid and an

ACE-inhibitor, but after another thrombus appeared, it was euthanized.

The authors concluded:

"A lameness or even a simple intolerance to effort are sufficient to suggest aortic thromboembolism, especially in a Cavalier King Charles."

April 2008:

Cavaliers are over-represented among dogs diagnosed with aortic

thrombosis in a UK study.

In an

April 2008 article, a team of UK researchers at the University of

Glasgow and the Royal (Dick) School (Gonçalves R, Penderis J [right], Chang YP,

Zoia A, Mosley J, Anderson TJ) examined the clinical records of

13 dogs diagnosed and treated for aortic thrombosis during 1004 through

2006 at the University of Glasgow veterinary school. Six (46%) of the 13

dogs were cavalier King Charles spaniels (CKCS). Four of the CKCSs with clinical

signs of cardiac disease were cavaliers. In the other two cavaliers,

protein losing nephropathy (PLN) was identified as a concurrent

condition. They report that:

In an

April 2008 article, a team of UK researchers at the University of

Glasgow and the Royal (Dick) School (Gonçalves R, Penderis J [right], Chang YP,

Zoia A, Mosley J, Anderson TJ) examined the clinical records of

13 dogs diagnosed and treated for aortic thrombosis during 1004 through

2006 at the University of Glasgow veterinary school. Six (46%) of the 13

dogs were cavalier King Charles spaniels (CKCS). Four of the CKCSs with clinical

signs of cardiac disease were cavaliers. In the other two cavaliers,

protein losing nephropathy (PLN) was identified as a concurrent

condition. They report that:

"There was an apparent male predisposition and the cavalier King charles spaniel was overrepresented. ... The cavalier King Charles spaniel is overrepresented (six of 13)."

RETURN TO TOP

Related Links

Veterinary Resources

Femoral artery occlusion in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. James W Buchanan, Andrew W. Beardow, Carl D. Sammarco. JAVMA. October 1997;211(7):872-874. Quote: Objective: To investigate development of femoral artery occlusion in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Design: Prospective study. Animals: 954 Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Procedure: 1,750 cardiovascular examinations consisting of visual inspection of mucous membranes, thoracic auscultation in areas associated with the heart valves, thoracic palpation, and palpation of the femoral arteries were made at 10 dog shows on 954 dogs. Findings of clinically normal, weak, or undetectable femoral pulses were recorded . Pathologic changes in occluded femoral arteries of 2 dogs were examined histologically. Results: Of the 954 dogs, 22 (2.3%) had an undetectable right or left femoral pulse on 1 or more examinations. Forty (4.2%) additional dogs had weak unilateral or bilateral femoral pulses. Only 1 dog had exercise intolerance, and it had coexistent congestive heart failure. Histologic examination of serial sections of an occluded femoral artery from 1 dog revealed intimal thickening with breaks in the internal elastic lamina proximal to the occluded segment. The occluded segment of the femoral artery was contracted and filled with an organizing, recanalizing thrombus. Similar histopathologic changes were found in sections of a femoral artery from another dog. Clinical Implications: Femoral artery occlusion is rare in other breeds and is not clinically important in dogs because of adequate collateral circulation; however, its rather common development in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels indicates a genetic predisposition and probable weakness in the femoral artery wall.

Aortic and iliac thrombosis in six dogs. A. Boswood, C. R. Lamb, R. N. White. J. Sm. Anim. Pract. March 2000. Quote: Six dogs had signs of pelvic limb weakness, pain and collapse as a result of occlusion of the distal aorta and/or the iliac arteries by a thrombus. Antemortem diagnosis was made on the basis of clinical signs, angiography and ultra-sonography. Five dogs had concurrent disease that probably predisposed to thrombosis, including hyperadreno-corticism (three dogs), neoplasia and cardiac disease. Two dogs died shortly after the episode of thrombosis. Dogs that survived the acute episode received aspirin in an attempt to prevent thrombosis occurring again and all regained pelvic limb function. For dogs that survived longer than one month after the acute episode, repeat thrombosis was uncommon; hence the prognosis was related to the underlying disease. ... Case 6: A six-year-old female neutered Cavalier King Charles spaniel (14 kg bodyweight) had immune-mediated polyarthritis. ... Iliac thrombosis was suspected on the basis of the physical signs; however, before antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy could be started the dog deteriorated further and died. Postmortem examination revealed the presence of a thrombus in the distal aorta at the site of bifurcation. The aortic thrombus appeared recent with no evidence of organisation. Within the iliac artery there was marked endothelial mineralisation and the thrombus was adherent to the wall at several points. ... The dog with iatrogenic HAC [hyperadrenocorticism] was a Cavalier King Charles spaniel. This breed has been reported by Buchanan to be predisposed to femoral artery occlusion. Affected individuals described did not demonstrate any clinical signs as a result of their arterial occlusion . The Cavalier reported in the present study, however, demonstrated marked clinical signs of ataxia, knuckling and paresis. Furthermore, occlusion of the distal aorta and right iliac artery was found, suggesting a different aetiology to those cases described by Buchanan. Aortic and iliac thrombosis in dogs is an uncommon condition that usually arises secondarily to a predisposing disease process; it carries a more favourable prognosis than feline aortic thromboembolism.

Pulmonary artery lesions in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Karlstam E, Häggström J, Kvart C, Jönsson L. Michaelsson, M. Vet. Rec. August 2000;147:166–167. Quote: Abstract Postmortem samples from 7 Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (aged 8-9 years) that died or been killed because of problems associated with chronic valvular disease (CVD) were examined. The findings included mitral CVD and dilation of the left atrium and ventricle in all dogs, and left atrial rupture in two and severe pulmonary artery thrombosis in one. all dogs also showed wrinkling and irregularity of the endothelial surface of the main pulmonary artery and its branches. The pulmonary artery wall showed sever intimal thickening due to subendothelial fibrosis and abundant vacuolated, Alcian blue-PAS-positive intercellular substances compatible with glycosaminoglycans (GAGS). GAGS were also found in the tunica media. In more sever cases the internal elastic lamina, separating the tunica intima from the tunica media was fragmented and poorly discernible. It is suggested that CVD is part of a more generalised connective tissue diseases. ... In cavalier King Charles spaniels, intimal thickening and breaks in the internal elastic lamina of the femoral artery have been reported (Buchanan and others 1997), and these lesions were associated with thrombosis and vascular occlusion. ... The cases presented here were seven consecutive, nonselected spaniels that underwent postmortem examination over a comparably short period of time. The observations reported indicate that pulmonary vascular lesions are common in middle-aged to old cavalier King Charles spaniels. However, the study does not allow a conclusion as to the true prevalence.

Determinants of weak femoral artery pulse in dogs with mitral valve prolapse. I. Tarnow, L. H. Olsen, M. B. Jensen, K. M. Pedersen, H. D. Pedersen. Res, Vet, Sci. April 2004; doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2003.10.001. Quote: In three substudies encompassing 247 dogs from two breeds predisposed to myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD), femoral artery pulse strength was palpated and related to potential explanatory factors, including quantitative echocardiographic measures of MMVD, aortic and femoral artery diameter and wall thickness and blood pressure. In addition, in 109 Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (of which 61 were included in the three substudies mentioned above), the relation between femoral artery pulse strength and presence of thrombocytopenia was investigated. ... A weak femoral artery pulse is a common finding in CKCS. ... No relation, however, was found between presence of thrombocytopenia and femoral artery pulse strength in this study. ... In conclusion, this study demonstrated that a weak femoral artery pulse is a common finding in CKCS and Dachshunds, and that the pulse strength in any one dog is reasonably reproducible. Pulse strength was found to be inversely related to heart rate, degree of obesity and MVP severity. In addition, femoral artery pulse strength decreased with age. The weak femoral artery pulses appear to reflect a decrease in diastolic artery diameter and/or systolic distension associated with a local decrease in blood flow, not artery occlusion or changes in pulse pressure and stroke volume. ... In 26% of the dogs, a pulse ⩽50% of normal strength was detected; six dogs (2.0%) had an absent pulse unilaterally or bilaterally. Mitral valve prolapse severity, degree of obesity, heart rate and age all influenced femoral artery pulse strength negatively. Weak femoral artery pulses were not related to clinical signs or to decreased pulse pressure or stroke volume. A weak femoral artery pulse reflected reduced artery diameter and/or distension rather than occlusion. In conclusion, weak femoral artery pulses in dogs with MMVD seem to be associated with regional/local reductions in blood flow and not arteriosclerosis or platelet count.

Aortic thromboembolism associated with Spirocerca lupi infection. Arnon Gal, Sigal Kleinbart, Zahi Aizenberg, Gad Baneth. Vet. Parasitology. June 2005;130(3-4):331-335. Quote: A 2-year-old male castrated Cavalier King Charles Spaniel was presented with paraplegia, cold caudal extremities and lack of femoral pulses. A 2 cm long thrombus occluding the aortic trifurcation and a 3 cm long abdominal aortic aneurysm with a thrombus were detected by ultrasonographic examination. The clinical and ultrasonographic findings were consistent with aortic thromboembolism. Anti-thrombotic and vasodilative therapy was not helpful and the dog was euthanized 3 days after the onset of paraplegia. A thrombus in the aortic trifurcation, multiple thoracic and abdominal aneurysms and a distal mediastinal esophageal granuloma containing Spirocera lupi worms were found on necropsy. The abdominal aortic aneurysms formed by S. lupi larval migration are believed to be responsible for the formation of the thrombus that occluded the aortic trifurcation. This is the first report of aortic thromboembolism associated with S. lupi infection.

Aortic Thromboembolism in Dogs: 21 Cases (1999-2004). Whelan MF, O’Toole TE, Lipitz L, Rozanski EA, Rush JE. J. Vet. Emerg. & Crtical Care. September 2005;15(3)(S1):S8-S9. Quote: Objective: To describe clinical signs, underlying disease, and outcome following treatment of aortic thromboembolism (ATE) in dogs. Procedure: Medical records of dogs with ATE based on abdominal ultrasonography were retrospectively evaluated. Results: Twenty-one cases were identified. Presenting complaints included vomiting, anorexia, lameness, rear limb weakness, and pain. Median duration of signs of ATE prior to hospital admission was 14 days (range 0.5–180 days). Concurrent diseases included: protein-losing nephropathy (6/21), cardiac disease (4/21), neoplasia (2/21), liver disease (2/21), diabetes mellitus (1/21), chronic urinary tract infections (1/21), hyperadrenocorticism (1/21), and unidentified (4/21). Owners of two dogs declined treatment. Dogs received treatment regimens including: anticoagulants (8/21); systemic thrombolytics (4/21); thrombolectomy via balloon catheterization (5/21); local thrombolytic infusion (tPA) via aortic catheterization (1/21), and limb amputation without adjunctive therapy (1/21). Ten dogs were euthanized, 4/21 died in the hospital, and 7/21 were discharged. Of the five dogs which had balloon catheterization for thrombolectomy, 3/5 died postoperatively, 1/5 was euthanized, and 1/5 was discharged but euthanized two months later. The dog with local thrombolytic infusion was euthanized. Of the four dogs receiving anticoagulants and systemic thrombolytics, three were euthanized and one died in the hospital. Of the two cases where treatment was declined, one was discharged and one was euthanized. Of the remaining dogs that were discharged, two died at home. Only 3/21 were reportedly doing well. Conclusion: Dogs with ATE had long-standing prior medical histories, and duration of signs was variable. Despite a variety of therapy plans, treatment was largely ineffective. Survival was poor.

Clinical and neurological characteristics of aortic thromboembolism in dogs. Gonçalves R, Penderis J, Chang YP, Zoia A, Mosley J, Anderson TJ. J Small Anim Pract. April 2008;49(4):178-84. Quote: To characterise the clinical presentation and neurological abnormalities in dogs affected by aortic thromboembolism. The medical records of 13 dogs diagnosed with aortic thromboembolism as the cause of the clinical signs, and where a complete neurological examination was performed, were reviewed retrospectively. ... Six dogs were cavalier King Charles spaniels. ... Four of the dogs with clinical signs of cardiac disease were cavalier King Charles spaniels. ... The onset was acute in only four dogs, chronic in five dogs (with all of these presenting as exercise intolerance) or chronic with acute deterioration in four dogs. Dogs with an acute onset of clinical signs were more severely affected exhibiting neurological deficits, while dogs with a chronic onset of disease predominantly presented with the exercise intolerance and minimal deficits. The locomotor deficits included exercise intolerance with pelvic limb weakness (five of 13), pelvic limb ataxia (one of 13), monoparesis (two of 13), paraparesis (two of 13), non-ambulatory paraparesis (two of 13) and paraplegia (one of 13). There was an apparent male predisposition and the cavalier King charles spaniel was overrepresented. ... The cavalier King Charles spaniel is overrepresented (six of 13). ... The rate of onset of clinical signs appears to segregate dogs affected by aortic thromboembolism into two groups, with different clinical characteristics and outcomes. Dogs with an acute onset of the clinical signs tend to be more severely affected, while dogs with a chronic onset predominantly present with exercise intolerance. It is therefore important to consider aortic thromboembolism as a differential diagnosis in dogs with an acute onset of pelvic limb neurological deficits and in dogs with longer standing exercise intolerance.

Aortic thromboembolism in a bitch. Chalus, T. de, Maurey-Guenec, C. : Summa, Animali da Compagnia. February 2011;28(2):56-60, ref.16. Quote: A female Cavalier King Charles is presented with a sudden lameness of the right hind leg. The clinical examination shows a weak femoral pulse, suggestive of aortic thromboembolism. The accessory examinations show a nephrotic syndrome, probably of idiopathic origin. The dog is treated with acetylsalicylic acid and an ACE-inhibitor, but after a new thrombus appears, it is euthanized. A lameness or even a simple intolerance to effort are sufficient to suggest aortic thromboembolism, especially in a Cavalier King Charles.

Canine aortic thromboembolism (2005–2011): a retrospective study of 50 cases. Guillaumin J, Hmelo S, Farrell K, Jandrey K, Sonnenshein S, Butler A. J. Vet. Emerg. & Crtical Care. August 2012;22(S2)(S1):S6. Quote: Introduction: To retrospectively describe a cohort population of dogs with distal aortic thromboembolism (ATE). To identify nonsurvivors characteristics and test a clinical severity score (CSS). Methods: Retrospective study in two academic teaching hospitals. Data included demographics, physical examination, clinical pathologic, imaging, treatment and outcome. CSS was based on presenting complaint, neurological deficits, femoral pulses and limb temperature. Fisher’s exact test, two sample t-test or one way ANOVA were used as appropriate to compare patient data with outcome or CSS. Results: Electronic medical record systems were searched for dogs with ATE. Fifty dogs (56% female) met inclusion criteria. Average(range) age was 10.7 years (1–17), and average body weight was 10.7 kg (4–45). Primary disease(s) potentially responsible were protein losing nephropathy (PLN) (n = 14), endocrine (n = 8), cryptogenic(n = 8), neoplasia (n = 7), multifactorial including PLN (n =6), multifactorial excluding PLN (n = 3), cardiac (n = 4). Overall survival was 50%. 28% were euthanized at presentation; 50% were hospitalized (56% of them subsequently discharged) and 22% were discharged without hospitalization. For all patients, median (95% CI) survival was 9.5 days (2–65). For patients not euthanized the first day (n = 36), it was 65 days (10–122). Diagnostics and treatment data will be presented. High creatine kinase and pain at admission were associated with high CSS (P = 0.008 and 0.0012, respectively). High CSS (P = 0.0005), low albumin (P = 0.0016), or high Urine Protein/Creatinine Ratio (P =0.026) were associated with euthanasia. There were no association between treatment and outcome. Conclusion: Canine ATE carries a guarded prognosis and outcome is correlated with severity of disease.

Aortic thromboembolism in dogs: retrospective evaluation of 51 cases. Morris B, O’Toole T, Rush J. J. Vet. Emerg. & Crtical Care. August 2012;22(S2)(S1):S8. Quote: Introduction: Aortic thromboembolism (ATE) in dogs is infrequently reported. Evaluation of dogs with ATE including clinical signs, history and outcome would provide useful information. Methods: Medical records of dogs with ATE were retrospectively evaluated for clinical signs, history, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. Results: Fifty-one cases were identified, 41 presented for pelvic limb signs, and 10 for non-specific complaints. Fifteen dogs were nonambulatory on presentation. Of these, eight had an acute presentation, and seven had acute deterioration of chronic signs. Twenty-eight dogs had absence of one (6), or both (22), femoral pulses. ATE was confirmed via abdominal ultrasound ornecropsy. Forty-five dogs had concurrent disease, including 24% with protein-losing nephropathy. Four dogs were discharged without treatment and 3 were euthanized on diagnosis. Of the treated dogs, forty-four received at least one of the following treatments: platelet inhibitors (26), anticoagulants (36), systemic thrombolysis(8), thrombolectomy via balloon catheterization (5), and local thrombolytic (tPA) infusion (3). Twenty-two treated dogs survived to discharge, however 10 died or were euthanized shortly thereafter.Twenty-two dogs were either euthanized (13) or died (9) in hospital. Of 51 dogs, 9 were alive at 180 days and 7 were lost to follow-up. Nonambulatory dogs were statistically less likely to survive to discharge (P < 0.0001). The presence or absence of pulses did not predict mortality (P = 0.093). Conclusion: Dogs with ATE resulting in nonambulation tend to have acute onset or acute deterioration of chronic signs and, regardless of the presence of pulses and method of treatment, have agrave prognosis.

Aortic thrombosis in dogs: 31 cases (2000–2010). Geri A. Lake-Bakaar, Eric G. Johnson, Leigh G. Griffiths. JAVMA. October 2012;241(7):910-915. Quote: Objective: To describe clinical signs, treatment, and outcome of aortic thrombosis in dogs. Design—Retrospective case series. Animals—31 dogs with aortic thrombosis. Procedures: Records were retrospectively reviewed and data collected regarding signalment, historical signs, physical examination findings, laboratory testing, definitive diagnosis, and presence of concurrent disease. Results: The records of 31 dogs with clinical or postmortem diagnosis of aortic thrombosis were reviewed. Onset of clinical signs was acute in 14 (45%) dogs, chronic in 15 (48%), and not documented in 2 (6%). Femoral pulses were subjectively weak in 6 (19%) dogs and absent in 17 (55%). Frequent laboratory abnormalities included high BUN concentration (n = 13), creatinine concentration (6), creatine kinase activity (10), and D-dimer concentration (10) and proteinuria with a urine protein–to–creatinine concentration ratio > 0.5 (12). Concurrent conditions included neoplasia (n = 6), recent administration of corticosteroids (6), and renal (8) or cardiac (6) disease. Median survival time was significantly longer for dogs with chronic onset of disease (30 days; range, 0 to 959 days) than for those with acute onset of clinical signs (1.5 days; range, 0 to 120 days). Conclusions and Clinical Relevance: Results suggested that aortic thrombosis is a rare condition in dogs and accounted for only 0.0005% of hospital admissions during the study period. The clinical signs for dogs with aortic thrombosis differed from those seen in feline patients with aortic thromboembolism. Median survival time was significantly longer for dogs with chronic disease than for dogs with acute disease. Despite treatment, outcomes were typically poor, although protracted periods of survival were achieved in some dogs.

Aortic thrombosis in dogs. Trevor P.E. Williams, Scott Shaw, Adam Porter, Larry Berkwitt. Vet. Emerg. & Critical Care. January 2017;27(1):9-22. Quote: Objective: To review information regarding etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment options for aortic thrombotic disease in dogs. Etiology: Diseases resulting in hypercoagulable states can cause thrombus formation in the distal aorta, and account for the majority of cases of aortic thrombosis (ATh) in dogs, although a substantial number of cases have no identifiable underlying cause. Aortic thromboembolism (ATE) also occurs but appears to be much less frequently documented. Diagnosis: The presentation of ATh and ATE in dogs is more varied compared to cats. Diagnosis can be challenging due to nonspecific clinical signs. Definitive diagnosis involves direct visualization of the thrombus, which is often obtained via ultrasound; however, other imaging modalities such as computed tomography scans can be utilized. ... Four of the 5 dogs with concurrent cardiac disease were Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, a breed commonly associated with mitral valve disease, putting into question the significance of the association of cardiac disease and ATh in this particular study. ... Therapy: The optimal treatment for aortic thrombotic disease in dogs has yet to be determined. Although not always possible, treatment of concurrent diseases that may promote thrombosis is an important aspect of thrombus resolution. A recent retrospective study reported positive results with long-term warfarin therapy; however, other studies have not reported similar results. Unfractionated or low-molecular weight heparins are additional anticoagulants that have been utilized. Platelet inhibitor therapy should also be considered in combination with anticoagulant therapy. Prognosis: Survival for dogs with ATh or ATE is reported to be between 50% and 60%. Dogs that present with chronic clinical signs appear to have a better prognosis than those who are acutely affected or those who are severely affected.

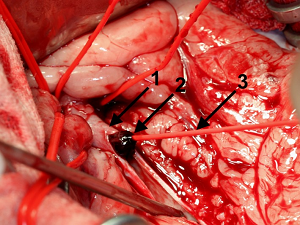

Vascular surgery of aortic thrombosis in a dog using Fogarty maneuver -

technical feasibility. Maartje Schwede, Olaf Richter, Michaele

Alef, Tobias Theuß, Shenja Loderstedt. Clinical Case Rpts. January

2018;6(1):214-219. Quote: Aortic thromboembolism is a rare and

life-threatening disease in dogs. This report aims to describe the

successful surgical

treatment

by use of a Fogarty Thrombectomy Catheter in an 8-year-old [male

Australian Shepherd] patient. The postsurgical intensive care therapy to

prevent ischemia-reperfusion syndrome is specified, despite poor outcome

in our case (owner elected euthanasia). ... For extraction of the

remaining thrombus, a 4 F Fogarty ‘Arterial Thrombectomy Catheter’ was

used. For this, the catheter was inserted in both directions through the

thrombus to the end of the vessel (about 20 cm). The catheter balloon

was insufflated and the catheter pulled back. [See photo of catheter

(#3) inserted in aorta (#1) and pulling the thrombus (#2) out.]

This manoeuver enables to retract all thrombotic material from distal

and proximal areas of the affected vascular region of the Aa. iliacae

externae and Aa. Iliacae internae. Thrombus adhesion to the aortic wall

was not apparent. Remaining small particles were flushed out of the

vessel with physiological sodium chloride solution. The aorta was closed

with a continuous suture and the abdomen according to standard

procedures.

treatment

by use of a Fogarty Thrombectomy Catheter in an 8-year-old [male

Australian Shepherd] patient. The postsurgical intensive care therapy to

prevent ischemia-reperfusion syndrome is specified, despite poor outcome

in our case (owner elected euthanasia). ... For extraction of the

remaining thrombus, a 4 F Fogarty ‘Arterial Thrombectomy Catheter’ was

used. For this, the catheter was inserted in both directions through the

thrombus to the end of the vessel (about 20 cm). The catheter balloon

was insufflated and the catheter pulled back. [See photo of catheter

(#3) inserted in aorta (#1) and pulling the thrombus (#2) out.]

This manoeuver enables to retract all thrombotic material from distal

and proximal areas of the affected vascular region of the Aa. iliacae

externae and Aa. Iliacae internae. Thrombus adhesion to the aortic wall

was not apparent. Remaining small particles were flushed out of the

vessel with physiological sodium chloride solution. The aorta was closed

with a continuous suture and the abdomen according to standard

procedures.

Outcome and treatments of dogs with aortic thrombosis: 100 cases (1997‐2014). Mackenzie Ruehl, Alex M. Lynch, Therese E. O'Toole, Bari Morris, John Rush, C. Guillermo Couto, Samantha Hmelo, Stacey Sonnenshein, Amy Butler, Julien Guillaumin. J. Vet. Intern. Med. August 2020; doi: 10.1111/jvim.15874. Quote: Background: Aortic thrombosis (ATh) is an uncommon condition in dogs, with limited understanding of risks factors, outcomes, and treatments. Objectives/Hypothesis: To describe potential risk factors, outcome, and treatments in dogs with ATh. Animals: Client-owned dogs with a diagnosis of ATh based on ultrasonographic or gross necropsy examination. Method: Multicentric retrospective study from 2 academic institutions. Results: One hundred dogs were identified. ... Only 2 dogs were Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and 7 were Shetland sheepdogs though those 2 breeds are identified as being commonly affected by ATh. ... Anti-thrombin diagnosis, 35/100 dogs were nonambulatory. The dogs were classified as acute (n = 27), chronic (n = 72), or unknown (n = 1). Fifty-four dogs had at least one comorbidity thought to predispose to ATh, and 23 others had multiple comorbidities. The remaining 23 dogs with no obvious comorbidities were classified as cryptogenic. Concurrent illnesses potentially related to the development of ATh included protein-losing nephropathy (PLN) (n = 32), neoplasia (n = 22), exogenous corticosteroid administration (n = 16), endocrine disease (n = 13), and infection (n = 9). Dogs with PLN had lower antithrom bin activity than those without PLN (64% and 82%, respectively) (P = .04). Sixty-five dogs were hospitalized with 41 subsequently discharged. Sixteen were treated as outpatient and 19 euthanized at admission. In-hospital treatments varied, but included thrombolytics (n = 12), alone or in combination with thrombectomy (n = 9). Fifty-seven dogs survived to discharge. Sixteen were alive at 180 days. Using regression analysis, ambulation status at the time of presentation was significantly correlated with survival-to-discharge (P < .001). Conclusions/Clinical Importance: Dogs with ATh have a poor prognosis, with nonambulatory dogs at the time of presentation having worse outcome. Although the presence of comorbid conditions associated with hypercoagulability is common, an underlying cause for ATh was not always identified.

Cardiovascular Disease in Companion Animals. Wendy A. Ware, John D. Bonagura, Brian A. Scansen. 2d ed. CRC Press. January 2022. Quote: Primary vascular disease as an underlying cause is suggested in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels by a genetic predisposition to femoral artery and pulmonary artery (PA) thrombosis.

Factors associated with thrombotic disease in dogs with renal proteinuria: A retrospective of 150 cases. Luca Fortuna, Harriet M. Syme. J. Vet. Intern. Med. December 2023; doi: 10.1111/jvim.16973. Quote: Background: Knowledge of additional risk factors for thrombotic disease (TD) among dogs with renal proteinuria is limited; these might differ for TD affecting the systemic arterial (AT), systemic venous (VT), and pulmonary circulation (PT). Hypothesis/Objectives: To compare signalment and clinicopathological data between dogs with renal proteinuria with or without TD, and between dogs with AT, VT, and PT. Animals: One hundred fifty client-owned dogs with renal proteinuria, 50 of which had TD. Methods: Retrospective case-controlled study. A database search (2004-2021) identified proteinuric dogs (UPC>2) with and without TD. Clinicopathological data were obtained from the records. TD and non-TD (NTD) groups were compared by binary logistic regression, and AT, VT, and PT groups by multinomial regression. Normal data presented as mean ± SD, non-normal data presented as median [25th, 75th percentiles]. Results: Cavalier King Charles Spaniels [CKCS] were overrepresented in the TD group (OR=98.8, 95% CI 2.09-4671, P=.02). ... Our study identified that CKCS with renal proteinuria had higher rates of TD compared to other breeds. CKCS have been identified as predisposed to AT, particularly aortic thrombosis, although this has not been specifically associated with PLN. All 5 dogs of this breed with TD had AT (1 case had concurrent PT), 4 of which were aortic, although breed was not a significantly associated factor in the analysis of thrombus location. Reasons suggested for a genetic predisposition of CKCS for TD include a connective tissue disorder, a subset of the breed having increased platelet reactivity, and their increased incidence of cardiac disease. MMVD was present in 4 out of 5 of the CKCS with TD and was a common comorbidity in dogs of other breeds with TD in this study; however, the proportions of dogs with this comorbidity were not different between TD cases and NTD cases, and MMVD is not considered a risk factor for TD. ... Compared to NTD cases, TD cases had higher concentration of neutrophils (11.06 [8.92, 16.58]×109/L vs 7.31 [5.63, 11.06]×109/L, p=.02), and lower concentration of eosinophils (0 [0, 0.21]×109/L vs 0.17 [0.04, 0.41]×109/L, P=.002) in blood, and lower serum albumin (2.45±0.73g/dL vs 2.83±0.73g/dL, P=.04). AT cases had higher serum albumin concentrations than VT cases (2.73±0.48g/dL vs 2.17±0.49g/dL, P=.03) and were older than PT cases (10.6±2.6 years vs 7.0±4.3 years, P=.008). VT cases were older (9.1±4.2 years vs 7.0±4.3 years, P=.008) and had higher serum cholesterol concentration (398 [309-692 mg/dL] vs 255 [155-402 mg/dL], P=.03) than PT cases. Conclusions and Clinical Importance: Differences between thrombus locations could reflect differences in pathogenesis.

CONNECT WITH US