Anesthesia and Sedatives in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels

-

MVD-affected

Cavaliers

MVD-affected

Cavaliers - Brachycephalic Cavaliers

- CM/SM-affected Cavaliers

- MCADD-affected Cavaliers

- Dexmedetomidine

- Other Consequences

- Research News

- Related Links

- What You Can Do

- Dedication

- Veterinary Resources

In general, dog deaths due to anesthesia (anaesthesia) during or following surgical procedures are rare occurances. In a November 2023 worldwide study of 55,022 dogs, the mortality rate was 0.69%, with 81% of those occurring after the operations.

Dogs affected with mitral valve disease (MVD) and/or brachycephalic (short-muzzled) dogs may have an increased risk to anesthesia and sedatives. Pre-anesthetic evaluation, premedication, induction, maintenance of anesthesia, and monitoring of anesthetized dogs and possible complications need to be taken into account.

In a March 2017 review of 1,269,582 dogs experiencing anesthetic episodes, including 982 dogs having anesthetic-related deaths, the researchers found that increasing age was associated with increased odds of death, as was undergoing non-elective procedures. The odds of death were significantly greater when pre-anesthetic physical examination results were not recorded or when pre-anesthetic hematocrit (Hct) levels (the ratio of the volume of red cells to the volume of whole blood) was outside the reference range. Underweight dogs had almost 15 times the odds of death as nonunderweight dogs. The only hematologic or physiologic variable identified as significant was Hct outside the reference range in dogs, which was associated with a 5.5-fold increase in the odds of death, compared with results for dogs that had values within the reference range.

RETURN TO TOP

MVD-affected Cavaliers

The main aims for managing anesthesia in dogs diagnosed with mitral valve disease (MVD) are:

• Maintenance of a high-normal heart rate;

• Maintenance of adequate cardiac output;

• Providing mild vasodilation; and

• Avoiding worsening of mitral regurgitation.

The dog's heart rate should be close to the normal rate obtained during the pre-anesthetic examination, in order to maintain cardiac output. Cardiac output needs to be maintained to insure adequate delivery of oxygen to the body's tissues. Mild vasodilation (widening of the blood vessels, particularly the arteries) is desirable to optimize cardiac output.

The pre-anesthetic physical examination of the MVD-affected dog should be thorough. Screening including echocardiography (ideally by a cardiologist) and bloodwork (hematology, biochemistry, electrolytes). Pre-anesthetic evaluation also should include identifying any risk factors for worsening MVD, including coughing, rapid respiration, exercise intolerance, syncope, and/or pre-syncope (collapse). -- essentially any symptoms of an MVD-affected dog in current Stage C or D.

Anesthesia tends to reduce blood pressure, which in turn may slightly

reduce the volume of mitral valve

regurgitation. Particularly in older

dogs, anesthesia may have an adverse effect upon the blood pressure and kidney function, rather than on any cardiac function.

ACE-inhibitors (e.g., enalapril, benazepril) should be

discontinued at least 24 hours before administering anesthesia,

because they can cause severe and possibly irreversible low blood

pressure (hypotension) due to the vasodilatory effects of anesthetic

agents, such as isoflurane. See this

September 2016 article for details.

regurgitation. Particularly in older

dogs, anesthesia may have an adverse effect upon the blood pressure and kidney function, rather than on any cardiac function.

ACE-inhibitors (e.g., enalapril, benazepril) should be

discontinued at least 24 hours before administering anesthesia,

because they can cause severe and possibly irreversible low blood

pressure (hypotension) due to the vasodilatory effects of anesthetic

agents, such as isoflurane. See this

September 2016 article for details.

Dogs with severe left atrial enlargement cannot excrete a sodium load efficently, and therefore during an anesthetic procedure, administration of a saline or lactated Ringer's solution (which contains sodium) is not recommended. Instead, an intravenous sugar solution of 5% dextrose in water (D5W) is advised.

Acepromazine, at a low dose, is a preferred pre-anesthetic agent for MVD-affected dogs. Acepromazine causes mild vasodilation, which is desirable at low doses as it assists in reducing afterload and lessens regurgitant flow of blood. However, a high dose of acepromazine could pose a risk of significant vasodilation resulting in hypotension.

Alpha-2-adrenergic receptor agonists, such as medetomidine and dexmedetomidine, should be avoided in MVD-affected dogs. This July 2021 article explains that peripheral vasoconstriction caused by these drugs can lead to significant increases in cardiac afterload and bradycardia, disrupting cardiac output.

The July 2021 article recommends that glycopyrrolate or atropine should be available in case of significant bradycardia. However, atropine may cause extreme tachycardia and increase cardiac oxygen demand.

Specialists recommend that an anticholinergic (Atropine or Glycopyrrolate) should be administered as needed during the procedure. The dog's heart rate and rhythm should be monitored durng the anesthetic procedure.

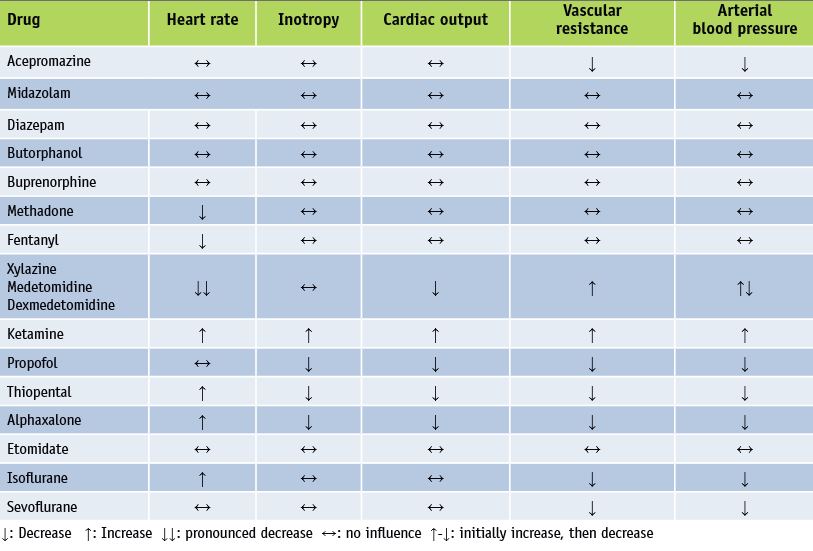

An excellent review of all aspects of anesthetizing dogs with MVD is discussed in this 2012 article by Austrian veterinarians Drs. Roswitha Steinbacher and René Dörfelt. See below this table from that article, listing "Cardiovascular effects of some important drugs used for anaesthesia". See also this very thorough outline of the process for cardiac patients, by the Veterinary Anesthesia & Analgesia Support Group.

In the August 2016 issue of Clinician's Brief, Colorado State University veterinarians Khursheed Mama and Marisa Ames thoroughly summarize the current views on the use of anesthesia on dogs in varying stages of mitral valve disease, as well as with common concurrent disorders. They state:

"Proper anesthetic management of patients with cardiac disease depends on the nature and severity of the disease. In a broad sense, the anesthetic approach to the cardiac patient is different for compensated vs decompensated heart disease. In addition, concurrent disease and requisite supportive therapies can cause decompensation of previously compensated heart disease. Understanding the underlying structural abnormalities and resultant physiologic consequences can influence the anesthesia protocol, periprocedural monitoring, and plans for emergency interventions."

In a November 2017 "Editor Annotation" in Advances in Small Animal Medicine and Surgery, the editor discusses if and when general practitioners should consider anesthetizing older MVD-affected dogs, as follows:

"[C]linicians should consider anesthetizing older dogs with mitral valve disease if (i) the mitral valve disease is not too severe; (ii) the condition requiring the anesthesia warrants immediate intervention; and (iii) the clinician is comfortable with the anesthetic and fluid protocols that reduce risk of anesthetic complications. All these factors should be considered and discussed with clients when deciding whether or not an anesthetic procedure is warranted and whether or not the patient should be referred to a specialty institution for more comprehensive assessment and monitoring."

In a March 2018 article in which sixteen dogs diagnosed with either Stage B1 or B2 MVD and all scheduled for dental treatment due to periodontal disease, all were placed under total intravenous anesthesia with propofol or induced with propofol and maintained with sevoflurane. The investigators reported that:

"Anaesthesia with propofol or with propofol and sevoflurane did not have any significant impact on oxidative stress parameters in dogs with early stage MMVD. In terms of oxidative stress, both protocols may be equally safely used in dogs with early stage MMVD."

In an August 2019 article, a team of Polish and Slovakian veterinary anesthesiologists compared propofol and alfazalone as intravenous anesthetics when used with midazolam, xylazine, and butorphanol during short-term (less than one-hour) surgeries of seven MVD-affected dogs (all Chihuahuas) in congestive heart failure. They concluded that:

The comparison of alfaxalone and propofol in the dogs with medically treated mitral valve regurgitation confirmed the possibility to use both ultrashort acting injection anaesthetics in surgeries terminated within one hour without significantly increased risk to the anaesthesia procedure. Alfaxalone confirmed the better influence in the respiratory frequency and heart rate, though the mean arterial blood pressures were lower in comparison with the propofol anaesthesia. Propofol confirmed a higher central nervous system depressive effect resulting in a significantly higher level of analgesia and a significantly shorter recovery period.

RETURN TO TOP

Brachycephalic Cavaliers

Care also should be taken when anesthesia may have to be administered

to cavaliers with short muzzles or other brachycephalic features.

Perianesthetic death (PAD) is defined

as death occurring within 48 hours of the dog being under an anesthetic.

Risk of death during the PAD period is higher for brachycephalic dogs.

See this

August 2018 article.

Care also should be taken when anesthesia may have to be administered

to cavaliers with short muzzles or other brachycephalic features.

Perianesthetic death (PAD) is defined

as death occurring within 48 hours of the dog being under an anesthetic.

Risk of death during the PAD period is higher for brachycephalic dogs.

See this

August 2018 article.

In a March 2012 report by a team of Tufts University veterinary anesthesiologists, cavaliers are among brachycephalic breeds which require special attention when being sedated and anesthetized. Their advice includes:

"Avoid excessive sedation. Avoid α2-agonists. Administer acepromazine at half dose. Preoxygenate. Use short-acting induction agent. Use appropriately sized endotracheal tubes. Extubate after patient is sitting up, vigorously chewing, bright, alert."

In an October 2018 article, Davies Veterinary Specialists vets review the current treatment protocols for anesthesia in brachycephalic dogs, in which they include cavaliers.

RETURN TO TOP

CM/SM-affected Cavaliers

The most accurate way of diagnosing Chiari-like malformation (CM) and syringomyelia (SM) is said to be through the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning. The MRI procedure requires that that patient be placed under anesthesia.

RETURN TO TOP

MCADD-affected Cavaliers

Cavaliers which are affected with the ACADM gene mutation causing medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase z9 deficiency (MCADD) require frequent meals or snacks to avoid seizures or other symptoms of MCADD. In preparation of surgeries requiring anesthesia, the veterinarian should be informed about the dog's condition. The vet may recommend that the dog be fed a meal or snack prior to surgery, while unaffected patients should not be fed anything for several hours prior to the anesthesia.

RETURN TO TOP

Dexmedetomidine

Dexmedetomidine often is used to sedate dogs before heart x-rays and

echocardiographs. It is an alpha-2 adrenoreceptor agonist.

Alpha-2 agonists have the effects of lowering both blood pressure and

heart rate.

Dexmedetomidine often is used to sedate dogs before heart x-rays and

echocardiographs. It is an alpha-2 adrenoreceptor agonist.

Alpha-2 agonists have the effects of lowering both blood pressure and

heart rate.

In a January 2016 report, researchers examined the effects of dexmedetomidine on six heart-healthy dogs undergoing chest x-rays and echocardiograms to determine if the sedative caused any changes in the resulting measurements. They found that the x-rays and echos performed after dosing dexmedetomidine resulted in significantly higher measurements of the vertebral heart score and cardiac size, and that moderate to severe mitral regurgitation and mild pulmonary regurgitation occurred in all six dogs. They concluded:

"Moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation and mild pulmonic regurgitation occurred in all dogs after dexmedetomidine administration. Findings indicated that dexmedetomidine could cause false-positive diagnoses of valvular regurgitation and cardiomegaly in dogs undergoing thoracic radiography and echocardiography."

Medetomidine is a combination of dexmedetomidine and another optical isomer, levomedetomidine. Atipamezole, an α2-adrenoceptor antagonist, is commonly used to reverse adverse effects of medetomidine upon the cardiovascular system. Another α2-adrenoceptor antagonist, vatinoxan, has been used in combination with either dexmedetomidine or medetomidine.

In a September 2023 article, medetomidine and vatinoxan were combined and compared with just medetomidine in anesthesizing 8 healthy laboratory beagles. The study was financed by the patent holder of the combination drug. The investigators concluded that:

"Overall, MED alone affected the cardiovascular system more negatively than MVX and the difference in cardiovascular function between the treatments can be considered clinically relevant."

RETURN TO TOP/a>

Other Consequences

In a July 2010 article, Dr. George Strain reported permanent hearing loss to 62 dogs and cats -- none being cavaliers -- following anesthesia for dental and ear cleaning procedures. Forty-three of the reported cases occurred after dental procedures, and 16 cases after ear cleanings. See also Dr. Strain's October 2012 article.

RETURN TO TOP

Research News

September 2020:

Cavalier with pulmonary valve stenosis had

post-surgical complications due to undetected right-to-left cardiac

shunt.

In an

August 2020 article, a team of PennVet clinicians (Dario A.

Floriano [right], Alexandra V. Crooks, Marc S. Kraus, Ciara A. Barr) performed

pre-surgical -- balloon valvulolasty -- cardiac examination of a

cavalier King Charles spaniel diagnosed with pulmonary valve stenosis, a

congenital cardiac defect. The day following the successful surgery, the

dog suffered hypoxia -- inadequate oxygen level in its blood -- and

displayed symptoms including neurologic episodes. The clinicians

diagnosed a right-to-left atrial level shunt (blood flowing directly

from the right artium to the left atrium and thereby not first traveling

through the lungs), using agitated-saline echocardiography. They

concluded and recommended:

In an

August 2020 article, a team of PennVet clinicians (Dario A.

Floriano [right], Alexandra V. Crooks, Marc S. Kraus, Ciara A. Barr) performed

pre-surgical -- balloon valvulolasty -- cardiac examination of a

cavalier King Charles spaniel diagnosed with pulmonary valve stenosis, a

congenital cardiac defect. The day following the successful surgery, the

dog suffered hypoxia -- inadequate oxygen level in its blood -- and

displayed symptoms including neurologic episodes. The clinicians

diagnosed a right-to-left atrial level shunt (blood flowing directly

from the right artium to the left atrium and thereby not first traveling

through the lungs), using agitated-saline echocardiography. They

concluded and recommended:

"Findings in the dog of the present report provided a reminder that patients could have multiple congenital cardiac defects. We recommend that before patients with congenital cardiac defects undergo general anesthesia, they first undergo full cardiac evaluation, including agitated-saline echocardiography to evaluate for a preexisting atrial-level shunt, and have their Spo2 and PCV evaluated so that potential shunt-related complications (eg, hypoxemia) may be more readily identified and addressed."

May 2020:

UK study of patent ductus arteriosus occlusion (PDA) finds

cavaliers were the most commonly represented breed.

In

a

May 2020 article, a team of UK investigators (Carmelo Parisi,

Victoria Phillips, Jacques Ferreira, Chris Linney, Alastair Mair

[right]) analysed the anesthetic management, complications, and

haemodynamic changes in 49 dogs undergoing surgical treatment of patent

ductus arteriosus (PDA) at a referred center in 2017 and 2018. The most

dogs of one breed among the 49 were five cavalier King Charles spaniels

(10.2%). Mixed breeds led the list with 13 dogs (26.5%). They report

that: (a) propofol was the most common induction agent (73.5%); (b)

general anaesthesia was maintained with isoflurane in oxygen in all

dogs; (c) complications included hypotension (63%), hypothermia (34%),

bradycardia (28%), arrhythmias (16%), hypertension (16%) and haemorrhage

(2%). They concluded tht hypotension was the most common complication

reported, and that no major adverse events were documented.

In

a

May 2020 article, a team of UK investigators (Carmelo Parisi,

Victoria Phillips, Jacques Ferreira, Chris Linney, Alastair Mair

[right]) analysed the anesthetic management, complications, and

haemodynamic changes in 49 dogs undergoing surgical treatment of patent

ductus arteriosus (PDA) at a referred center in 2017 and 2018. The most

dogs of one breed among the 49 were five cavalier King Charles spaniels

(10.2%). Mixed breeds led the list with 13 dogs (26.5%). They report

that: (a) propofol was the most common induction agent (73.5%); (b)

general anaesthesia was maintained with isoflurane in oxygen in all

dogs; (c) complications included hypotension (63%), hypothermia (34%),

bradycardia (28%), arrhythmias (16%), hypertension (16%) and haemorrhage

(2%). They concluded tht hypotension was the most common complication

reported, and that no major adverse events were documented.

September 2019:

Polish and Slovakian anesthesiologists find

alfaxalone and propofol are safe and effective in short-timed surgeries

of MVD-affected dogs.

In an

August 2019 article, and team of Polish and

Slovakian veterinary anesthesiologists (Igor Capik [right],

Isabela Polkowska, Branislav Lukac) compared propofol and alfazalone

as intravenous anesthetics when used with midazolam, xylazine, and

butorphanol during short-term (less than one-hour) surgeries of seven

MVD-affected dogs (all Chihuahuas) in congestive heart failure. They concluded that:

In an

August 2019 article, and team of Polish and

Slovakian veterinary anesthesiologists (Igor Capik [right],

Isabela Polkowska, Branislav Lukac) compared propofol and alfazalone

as intravenous anesthetics when used with midazolam, xylazine, and

butorphanol during short-term (less than one-hour) surgeries of seven

MVD-affected dogs (all Chihuahuas) in congestive heart failure. They concluded that:

The comparison of alfaxalone and propofol in the dogs with medically treated mitral valve regurgitation confirmed the possibility to use both ultrashort acting injection anaesthetics in surgeries terminated within one hour without significantly increased risk to the anaesthesia procedure. Alfaxalone confirmed the better influence in the respiratory frequency and heart rate, though the mean arterial blood pressures were lower in comparison with the propofol anaesthesia. Propofol confirmed a higher central nervous system depressive effect resulting in a significantly higher level of analgesia and a significantly shorter recovery period.

December 2018:

Pre-anesthesia sedatives methadone and acepromazine are found to

decrease tear production in dogs.

In a

December 2018 article, a team of UK anesthesiologists and

ophthalmologists (Hayley A. Volk [right], Ellie West, Rose Non

Linn-Pearl, Georgina V. Fricker, Ambra Panti, David J. Gould) studied the tear production in the eyes of 30 dogs,

including two cavalier King Charles spaniels, which were to receive

anesthesia for general non-ocular surgeries. Each dog was to receive

customary intra-muscular injections of pre-medication sedatives of both

methadone and acepromazine. Each dog's eyes were Schirmer tear tested

(STT) both before and after injection of the sedatives. The results

showed a reduction in tear production after administration of the two

sedatives. Nine of the dogs, including one of the two cavaliers, had STT

readings following the sedation drop below 15mm/minute. Clinically

normal dogs' STT readings should be greater than 15mm/min. For that

cavalier (dog #26), her STT reading dropped from 21.5mm/min. before

sedation to 11mm/min following sedation. For the other cavalier (dog

#22), her pre-sedation STT reading was 19.5 and her post-sedation STT

reading was borderline at 15.5mm/min. The investigators concluded that:

In a

December 2018 article, a team of UK anesthesiologists and

ophthalmologists (Hayley A. Volk [right], Ellie West, Rose Non

Linn-Pearl, Georgina V. Fricker, Ambra Panti, David J. Gould) studied the tear production in the eyes of 30 dogs,

including two cavalier King Charles spaniels, which were to receive

anesthesia for general non-ocular surgeries. Each dog was to receive

customary intra-muscular injections of pre-medication sedatives of both

methadone and acepromazine. Each dog's eyes were Schirmer tear tested

(STT) both before and after injection of the sedatives. The results

showed a reduction in tear production after administration of the two

sedatives. Nine of the dogs, including one of the two cavaliers, had STT

readings following the sedation drop below 15mm/minute. Clinically

normal dogs' STT readings should be greater than 15mm/min. For that

cavalier (dog #26), her STT reading dropped from 21.5mm/min. before

sedation to 11mm/min following sedation. For the other cavalier (dog

#22), her pre-sedation STT reading was 19.5 and her post-sedation STT

reading was borderline at 15.5mm/min. The investigators concluded that:

"Intramuscular combinations of acepromazine and methadone in dogs may add to the risk of ocular morbidities, such as corneal ulceration, in susceptible individuals."

April 2018:

Japanese researchers find dobutamine offsets the negative

effects of isoflurane on MVD-affected dogs.

In an

April 2018 article, Japanese researchers (Seijirow Goya, Tomoki

Wada, Kazumi Shimada, Daiki Hirao, Ryou Tanaka [right]) studied the effects of

combining the use of isoflurane and dobutamine on arterial pressure in

MVD-affected dogs not yet in heart failure. They found that isoflurane

reduces blood pressure mainly due to depressing the action of the heart

muscle, rather than dilating blood vessels. The results showed that

dobutamine increased arterial pressure by increasing contractility and

countering the depressant effect of isoflurane. They concluded:

In an

April 2018 article, Japanese researchers (Seijirow Goya, Tomoki

Wada, Kazumi Shimada, Daiki Hirao, Ryou Tanaka [right]) studied the effects of

combining the use of isoflurane and dobutamine on arterial pressure in

MVD-affected dogs not yet in heart failure. They found that isoflurane

reduces blood pressure mainly due to depressing the action of the heart

muscle, rather than dilating blood vessels. The results showed that

dobutamine increased arterial pressure by increasing contractility and

countering the depressant effect of isoflurane. They concluded:

"In conclusion, in dogs with experimentally-induced MI, isoflurane decreased arterial pressure by reducing cardiac contractility. Infusion of dobutamine increased arterial pressure without increasing LAP by enhancing the attenuated contractility in MI dogs with isoflurane-induced hypotension."

November 2017:

Study of 88 MVD-affected dogs under anesthesia during dental

procedures finds no increased risk for complications.

A

July 2017 article reviewed the study of 200 dogs which underwent

anesthesia during routine dental procedures at the North Carolina State

University's veterinary teaching hospital between 2006 and 2011. The

researchers (Jennifer E. Carter, Alison A. Motsinger-Reif, William V.

Krug, Bruce W. Keene [right]) classified two groups: one group

of 100 dogs with heart disease (66 having mitral valve disease and 22

others suspected of having MVD), and the other group of 100

heart-healthy dogs. The researchers reviewed the medical records of the

dogs to evaluate the occurrence of anesthetic complications. They found

that no dogs died in either group, and no significant differences were

found between the groups in any of the anesthetic complications

evaluated, although dogs in the heart disease group were significantly

older. Midazolam and etomidate were used more frequently, and alpha-2

agonists used less frequently, in the heart disease group compared to

controls. They concluded that the study suggests dogs with heart

disease, when anesthetized by trained personnel and carefully monitored

during routine dental procedures, are not at significantly increased

risk for anesthetic complications.

A

July 2017 article reviewed the study of 200 dogs which underwent

anesthesia during routine dental procedures at the North Carolina State

University's veterinary teaching hospital between 2006 and 2011. The

researchers (Jennifer E. Carter, Alison A. Motsinger-Reif, William V.

Krug, Bruce W. Keene [right]) classified two groups: one group

of 100 dogs with heart disease (66 having mitral valve disease and 22

others suspected of having MVD), and the other group of 100

heart-healthy dogs. The researchers reviewed the medical records of the

dogs to evaluate the occurrence of anesthetic complications. They found

that no dogs died in either group, and no significant differences were

found between the groups in any of the anesthetic complications

evaluated, although dogs in the heart disease group were significantly

older. Midazolam and etomidate were used more frequently, and alpha-2

agonists used less frequently, in the heart disease group compared to

controls. They concluded that the study suggests dogs with heart

disease, when anesthetized by trained personnel and carefully monitored

during routine dental procedures, are not at significantly increased

risk for anesthetic complications.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The number of cavalier King Charles spaniels among the 66 MVD-affected dogs was not listed in the article. In a November 2017 review of this July 2017 article, the editors made these critical observations about the article:

“However, several caveats and questions about the study exist. ... It would have been better to limit the study to just the 88 dogs with mitral valve disease.

"Second, the authors did not describe the severity of the heart disease in any detail – they simply stated that these dogs had ‘some evidence of cardiac enlargement, with or without a history of congestive heart failure’ (which was being effectively controlled with medications). Therefore, it is very difficult to determine just how severely affected these dogs were. It is possible that many of them had mild disease – a situation that would not be of anesthetic concern. The ASA [American Society of Anesthesiologists] ratings for these dogs were Grade 2 (mild risk) or Grade 3 (moderate risk) for almost all dogs, suggesting that most dogs were not severely affected.

"Third, the authors observed that anesthesiologists used different drug protocols in the dogs with heart disease, with a much higher use of midazolam and etomidate than in the control dogs (matched dogs without heart disease). Therefore, the dogs in each group were not treated equally.

"Fourth, the authors did not consider post-anesthetic complications. ... It is possible that dogs with mitral valve disease might have developed congestive heart failure shortly after discharge, as a result of the stress of the procedure, or fluid overload.

"Finally, these results were obtained from dogs anesthetized by trained anesthesiologists in a referral institution (veterinary teaching hospital). Therefore, extrapolating these findings to general practice is, at best, a long stretch. Whether practitioners with minimal training in anesthesia and no dedicated anesthetic staff monitoring the patients would achieve the same outcomes cannot be determined. Having said that, clinicians should consider anesthetizing older dogs with mitral valve disease if (i) the mitral valve disease is not too severe; (ii) the condition requiring the anesthesia warrants immediate intervention; and (iii) the clinician is comfortable with the anesthetic and fluid protocols that reduce risk of anesthetic complications. All these factors should be considered and discussed with clients when deciding whether or not an anesthetic procedure is warranted and whether or not the patient should be referred to a specialty institution for more comprehensive assessment and monitoring.”

September 2016: CSU vets aptly summarize using anesthesia on MVD-affected dogs. In the August 2016 issue of Clinician's Brief, Colorado State University veterinarians Khursheed Mama and Marisa Ames thoroughly summarize the current views on the use of anesthesia on dogs in varying stages of mitral valve disease, as well as with common concurrent disorders. They state:

"Proper anesthetic management of patients with cardiac disease depends on the nature and severity of the disease. In a broad sense, the anesthetic approach to the cardiac patient is different for compensated vs decompensated heart disease. In addition, concurrent disease and requisite supportive therapies can cause decompensation of previously compensated heart disease. Understanding the underlying structural abnormalities and resultant physiologic consequences can influence the anesthesia protocol, periprocedural monitoring, and plans for emergency interventions."

March 2016: Study shows that the heart x-ray and echo sedative dexmedetomidine can cause false diagnoses of MVD and heart enlargement. Dexmedetomidine often is used to sedate dogs before heart x-rays and echocardiographs. In a January 2016 report, a team of Taiwan researchers examined the effects of dexmedetomidine on six heart-healthy dogs undergoing chest x-rays and echocardiograms to determine if the sedative caused any changes in the resulting measurements. They found that the x-rays and echos performed after dosing dexmedetomidine resulted in significantly higher measurements of the vertebral heart score and cardiac size, and that moderate to severe mitral regurgitation and mild pulmonary regurgitation occurred in all six dogs. They concluded:

"Findings indicated that dexmedetomidine could cause false-positive diagnoses of valvular regurgitation and cardiomegaly in dogs undergoing thoracic radiography and echocardiography."

March 2012: Cavaliers are listed among brachycephalic breeds requiring extra care when being anesthetized. In a March 2012 report by a team of Tufts University veterinary anesthesiologists, cavaliers are among brachycephalic breeds which require special attention when being sedated and anesthetized. Their advice includes:

"Avoid excessive sedation. Avoid α2-agonists. Administer acepromazine at half dose. Preoxygenate. Use short-acting induction agent. Use appropriately sized endotracheal tubes. Extubate after patient is sitting up, vigorously chewing, bright, alert."

RETURN TO TOP

Related Links

RETURN TO TOP

What You Can Do

If and when your cavalier is going to have an anesthetic procedure, make sure your veterinarian knows in advance about the possible hazards to your dog, and offer the veterinarian a copy of this 2012 article by Austrian veterinarians Drs. Roswitha Steinbacher and René Dörfelt, and a copy of this 2016 article by Colorado State University veterinarians Khursheed Mama and Marisa Ames.

Following the anesthesia procedure, the dog's liver should be detoxified. Supplements including milk thistle, N-acetyl cystine (NAC), S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe), and CoQ10 may be given in specific quantities daily for a week thereafter.

Do you need to find a board certified anesthesiologist? Here is a link to a locator website.

RETURN TO TOP

Dedication

Dedication

This article is dedicated to a ten year old male cavalier King Charles spaniel named Quiggs (right), who died in July 2015 of a cardiac reaction to anesthesia and sedation during a routine dental cleaning procedure.

RETURN TO TOP

Veterinary Resources

Post-anesthesia deafness in dogs and cats following dental and ear cleaning procedures. Cathryn K. Stevens-Sparks, George M. Strain. Vet. Anaesthesia & Analgesia. July 2010;37(4):347-351. Quote: Objective: The present study was performed to document hearing loss in dogs and cats following procedures performed under anesthesia. Most cases of reported hearing loss were subsequent to dental and ear cleaning procedures. Study design: Prospective and retrospective case survey. Animals: Subjects were dogs and cats with deafness, personally communicated to one author, cases discussed on a veterinary information web site, and cases communicated through a survey of general practice and dental specialist veterinarians. Methods: Reported deafness cases were characterized by species (dog, cat), breed, gender, age, and dog breed size. Results: Sixty-two cases of hearing loss following anesthesia were reported between the years 2002 and 2009. Five additional cases were reported by survey respondents. Forty-three cases occurred following dental procedures. Sixteen cases occurred following ear cleaning. No relationship was observed between deafness and dog or cat breed, gender, anesthetic drug used, or dog size. Geriatric animals appeared more susceptible to post-anesthetic, post-procedural hearing loss. Conclusions: Deafness may occur in dogs and cats following anesthesia for dental and ear cleaning procedures, but the prevalence is low. The hearing loss appears to be permanent.

Breed-Specific Anesthesia. Stephanie Krein, Lois A. Wetmore. NAVA Clinicians Brief; March 2012; 17-20. Quote: "Certain breed differences can lead to greater risks for airway obstruction, increased responsiveness to anesthetic drugs, and delayed recovery, all of which can result in increased anesthesia-related morbidity and mortality. ... If cardiac disease is suspected, a full cardiac workup with a veterinary cardiologist is recommended. ... Brachycephalic Breeds (e.g. bulldog, pug, Boston terrier, boxer, Cavalier King Charles spaniel, Pekingese). Problem: Brachycephalic airway syndrome; increased respiratory effort; potential for upper airway obstruction. Avoid excessive sedation. Avoid α2-agonists. Administer acepromazine at half dose. Preoxygenate. Use short-acting induction agent. Use appropriately sized endotracheal tubes. Extubate after patient is sitting up, vigorously chewing, bright, alert. ... Brachycephalic breeds have anatomic considerations that may affect anesthetic outcome.Most brachycephalic breeds suffer from brachycephalic airway syndrome (BAS), which is characterized by stenotic nares, elongated soft palate, everted laryngeal saccules, and hypoplastic trachea. Affected dogs have narrower upper airways than do dogs with normal anatomic features. Because in brachycephalic breeds additional airway contraction can occur with stress (ie, increased respiratory effort, turbulent flow), clinicians need to be prepared for possible upper airway obstruction. Furthermore, brachycephalic dogs must be monitored closely after premedication, throughout anesthesia and the postoperative period, and after extubation. An oxygen source and endotracheal tube should be readily available. Many brachycephalic dogs respond well to acepromazine in conjunction with an opioid; however, the sedative dose should be half of that used for nonbrachycephalic dogs. Full mu-opioid agonists can be used but because they may cause excessive respiratory depression, a reversal agent should be available. Dexmedetomidine should be avoided because of the presence of high vagal tone in these breeds. Anticholinergics, such as glycopyrrolate, may be used to decrease airway secretions and counteract high vagal tone. Preoxygenation is recommended before dogs with BAS are induced. Propofol or a similar short-acting drug should be used for induction and intubation should be completed as rapidly as possible.Mask inductions should be avoided, and smaller endotracheal tubes should be used. Because brachycephalic breeds tend toward obesity, controlled or mechanical ventilation is often necessary.Most problems associated with mechanical ventilation occur during induction and recovery, so monitoring is particularly important. Extubation should be postponed until the patient is bright, alert, swallowing—even chewing on the endotracheal tube. If extubation is attempted while the patient is sedated and groggy from anesthesia, there is increased risk for upper airway obstruction. If upper airway obstruction occurs, the patient should be reintubated."

Canine Deafness. George M. Strain. Vety.Clinics.Sm.Anim.Pract. Oct.2012. Quote: Conductive deafness, caused by outer or middle ear obstruction, may be corrected, whereas sensorineural deafness cannot. Most deafness in dogs is congenital sensorineural hereditary deafness, associated with the genes for white pigment: piebald or merle. The genetic cause has not yet been identified. Dogs with blue eyes have a greater likelihood of deafness than brown-eyed dogs. Other common forms of sensorineural deafness include presbycusis, ototoxicity, noise-induced hearing loss, otitis interna, and anesthesia. ... Definitive diagnosis of deafness requires brainstem auditory evoked response testing. ... Anesthesia-Associated Deafness: Although uncommon, some dogs or cats that undergo anesthesia, especially fordental cleaning procedures, recover from anesthesia with bilateral deafness that in most cases is permanent. In a study of 62 reported cases in dogs and cats, no association was observed between deafness and breed, gender, anesthetic drug used, or dog size. Forty-three of the reported cases occurred after dental procedures, and 16 cases after ear cleanings. Geriatric animals seemed more susceptible to the hearingloss, which might reflect a bias because of dental procedures being performed more often on older animals. In at least one case, deafness was the result of a persistent otitis media with effusion, suggesting possible eustachian tube dysfunction subsequent to vigorous jaw manipulation during a dental procedure (unpublished observation). For most cases the cause is unknown and ongoing studies are pursuing possible mechanisms.

Anaesthesia in dogs and cats with cardiac disease – An impossible endeavour or a challenge with manageable risk? R. Steinbacher, R. Dörfelt. Wiener Tierärztliche Monatsschrift – Veterinary Medicine Austria. 2012. Quote: "Anaesthesia in patients with mitral valve insufficiency: Heart rate and blood pressure should be assessed already during preanaesthetic examination, in order to obtain reference values for intraoperative monitoring of these parameters. During anaesthesia, an increase of regurgitation must be avoided. Therefore, no centrally effective α2-agonists or massive infusion therapy should be given to avoid any increase in afterload. In these patients, a significant decrease in heart rate also leads to increased regurgitation as the increased ventricular filling enhances contractility. Any drugs, which induce an increase in vascular tone and, consequently, in afterload, like dopamine (in vasoconstrictive doses) and ephedrine, should also be avoided. Reducing the systemic vascular resistance by administering very small doses of acepromazine as a premedication in order to reduce the afterload is beneficial, as it reduces regurgitation and increases cardiac output despite reduced contractility. Excessive vasodilation, however, causes a drop in blood pressure, which in most cases can hardly be compensated for by the patient. Opioids like methadone or butorphanol, in combination with acepromazine, produce adequate sedation and, in addition, analgesia. As opioids, above all µ-agonists (e.g. methadone), can reduce the heart rate if administered at higher doses, an anticholinergic drug (like atropine or glycopyrrolate) should always be at hand when µ-agonists are used, in order to be prepared in case a drop in heart rate should occur. Whenever possible, induction of anaesthesia should be performed under complete monitoring and good preoxygenation. In severe cases, etomidate is a good choice as it has minimum cardiovascular side effects. In stable patients, low doses of ketamine can be used as an alternative, together with benzodiazepines or low doses of propofol. Negative inotropic drugs like propofol at high doses and thiopental can increase the regurgitation fraction in patients with severe valvular disease due to reduced forward propulsion of the blood and should therefore be used with caution. To maintain anaesthesia, inhalation anaesthetics can be used at concentrations that should be as low as possible. Another possibility is a partial or total intravenous anaesthesia using propofol, fentanyl or ketamine combinations (subanaesthetic doses). In case hypotension and bradycardia should occur, these can be treated by administration of anticholinergics. In doing so, the target heart rate should lie within the preanaesthetic range or slightly above. Should hypotension not be accompanied by bradycardia and not return to normal levels after reducing the concentration of the inhalant, positive inotropic drugs like dobutamine should preferably be administered."

Management and complications of anaesthesia during balloon valvuloplasty for pulmonic stenosis in dogs; 39 cases (2000 to 2012). R. V. Ramos, B. P. Monteiro-Steagall, P. V. M. Steagall. J. Sm. Anim. Pract. January 2014; doi: 10.1111/jsap.12182. Quote: Objectives: The aim of this study was to report the management and complications of anaesthesia in dogs undergoing balloon valvuloplasty. Methods: A retrospective review of medical records of dogs that were diagnosed with pulmonic stenosis and undergoing balloon valvuloplasty between 2000 and 2012. Results: Thirty-nine cases were identified (28 males and 11 females). Median (range) age and bodyweight was 6 (4 to 48) months and 11·5 (2·0 to 30·3) kg, respectively. The most commonly represented breeds included mixed breed (n=7, 17·9%) and English bulldog (n=6, 15·3%) [including 3 cavalier King Charles spaniels (7.6%), second highest breed]. Anaesthesia was induced most commonly with intravenous administration of ketamine-diazepam (n=8, 20·5%), propofol-diazepam (n=8, 20·5%), or propofol-midazolam-lidocaine (n=6, 15·4%), and maintained with isoflurane in combination with fentanyl or lidocaine. Anaesthetic and surgery times (mean ±sd) were 268·5 ±54 minutes and 193·2 ±50 minutes, respectively. The most common intraoperative complications were hypotension (n=19, 48·7%), bradycardia (n=8, 20·5%) and desaturation (n=7, 17·9%). Cardiac arrhythmias were observed in 21 (53·8%) dogs. Death occurred in one (2·6%) dog [French bulldog] due to severe hypotension after ballooning followed by cardiac arrest. Clinical Significance: Successful anaesthesia can be performed in young dogs with pulmonic stenosis undergoing balloon valvuloplasty. Management of anaesthesia requires intense monitoring and immediate treatment of complications. Anaesthetic risk increases during ballooning and may result in cardiac arrest.

Effects of intravenous dexmedetomidine on cardiac characteristics measured using radiography and echocardiography in six healthy dogs. Hsien-Chi Wang, Cih-Ting Hung, Wei-Ming Lee, Kui-Ming Chang, Kuan-Sheng Chen. Vet. Radiology & Ultrasound. January 2016;57(1):8-15. Quote: "Dexmedetomidine is a highly specific and selective α2-adrenergic receptor agonist widely used in dogs for sedation or analgesia. We hypothesized that dexmedetomidine may cause significant changes in radiographic and echocardiographic measurements. The objective of this prospective cross-sectional study was to test this hypothesis in a sample of six healthy dogs. Staff-owned dogs were recruited and received a single dose of dexmedetomidine 250 μg/m2 intravenously. Thoracic radiography and echocardiography were performed 1 h before treatment, and repeated 10 and 30 min after treatment, respectively. One observer recorded cardiac measurements from radiographs and another observer recorded echocardiographic measurements. Vertebral heart score and cardiac size to thorax ratio on the ventrodorsal projection increased from 9.8 ± 0.6 v to 10.3 ± 0.7 v (P = 0.0007) and 0.61 ± 0.04 to 0.68 ± 0.03 (P = 0.0109), respectively. E point-to-septal separation and left ventricle internal diameter in diastole and systole increased from 2.4 ± 1.1 to 6.6 ± 1.9 mm, 32.3 ± 8.1 to 35.5 ± 8.8 mm, and 19.4 ± 6 to 27.0 ± 7.2 mm, respectively (P < 0.05). Fractional shortening and sphericity index decreased from 40.7 ± 5.8 to 24.4 ± 2.9%, and 1.81 ± 0.07 to 1.58 ± 0.04, respectively (P < 0.05). Moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation and mild pulmonic regurgitation occurred in all dogs after dexmedetomidine administration. Findings indicated that dexmedetomidine could cause false-positive diagnoses of valvular regurgitation and cardiomegaly in dogs undergoing thoracic radiography and echocardiography."

Anesthesia for Dogs with Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease. Khursheed Mama, Marisa Ames. Clinician's Brief. August 2016. Quote: Proper anesthetic management of patients with cardiac disease depends on the nature and severity of the disease. In a broad sense, the anesthetic approach to the cardiac patient is different for compensated vs decompensated heart disease. In addition, concurrent disease and requisite supportive therapies can cause decompensation of previously compensated heart disease. Understanding the underlying structural abnormalities and resultant physiologic consequences can influence the anesthesia protocol, periprocedural monitoring, and plans for emergency interventions. This discussion focuses on the anesthetic management of dogs with varying stages of myxomatous mitral valve disease and commonly observed comorbidities.

Effects of orally administered enalapril on blood pressure and hemodynamic response to vasopressors during isoflurane anesthesia in healthy dogs. Amanda E. Coleman, Molly K. Shepard, Chad W. Schmiedt, Erik H. Hofmeister, Scott A. Brown. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. September 2016; doi: 10.1111/vaa.12338. Quote: Objective: To examine whether preanesthetic administration of enalapril, compared with placebo, results in a greater decline in blood pressure (BP) or decreased responsiveness of BP to isotonic fluids or vasopressors in healthy dogs during isoflurane anesthesia. Study design: Randomized, experimental, placebo-controlled, blinded, crossover study. Animals: Twelve healthy, female, purpose-bred beagles. Methods: Dogs underwent the following week-long treatment protocols, each preceded by a 1 week washout period: oral placebo twice daily (PLA); oral enalapril, 0.5 mg kg−1 twice daily, with the 15th dose withheld on the day of anesthesia (ENA-W), and oral enalapril, 0.5 mg kg−1 twice daily, with the 15th dose administered 90 minutes prior to anesthetic induction (ENA). On day 8 of each treatment period, dogs were anesthetized in random order utilizing a standard protocol. Following stabilization at an end-tidal isoflurane concentration (Fe′Iso) of 1.3%, invasively measured systolic (SAP), diastolic (DAP) and mean (MAP) arterial blood pressure were continuously recorded via telemetry. Hypotension (SAP < 85 mmHg) was treated with the following sequential interventions: lactated Ringer's solution (LRS) bolus (10 mL kg−1); repeated LRS bolus; dopamine (7 μg kg−1 min−1); and dopamine (10 μg kg−1 min−1) first without and then with vasopressin (1 mU kg−1 hour−1). Results: Compared with the PLA but not the ENA-W group, the ENA group had significantly lower average SAP, DAP and MAP at an Fe′Iso of 1.3%, spent more minutes in hypotension, and required a greater number of interventions to correct moderate-to-severe mean arterial hypotension. Conclusions: In healthy dogs, enalapril administered 90 minutes prior to isoflurane anesthesia increases the degree of intra-anesthetic hypotension and the number of interventions required to correct moderate-to-severe hypotension. Clinical relevance: Dogs receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on the day of anesthesia may exhibit clinically significant intra-anesthetic hypotension.

Factors associated with anesthetic-related death in dogs and cats in primary care veterinary hospitals. Nora S. Matthews, Thomas J. Mohn, Mingyin Yang, Nathaniel Spofford, Alison Marsh, Karen Faunt, Elizabeth M. Lund, Sandra L. Lefebvre. J. Amer. Vet. Med. Assn. March 2017;250(6):655-665. Quote: Objective: To identify risk factors for anesthetic-related death in pet dogs and cats. Design: Matched case-control study. Animals: 237 dogs and 181 cats. Procedures: Electronic medical records from 822 [Banfield] hospitals were examined to identify dogs and cats that underwent general anesthesia (including sedation) or sedation alone and had death attributable to the anesthetic episode ≤ 7 days later (case animals; 115 dogs and 89 cats) or survived > 7 days afterward (control animals [matched by species and hospital]; 122 dogs and 92 cats). Information on patient characteristics and data related to the anesthesia session were extracted. Conditional multivariable logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated with anesthetic-related death for each species. Results: The anesthetic-related death rate was higher for cats (11/10,000 anesthetic episodes [0.11%]) than for dogs (5/10,000 anesthetic episodes [0.05%]). Increasing age was associated with increased odds of death for both species, as was undergoing nonelective (vs elective) procedures. Odds of death for dogs were significantly greater when preanesthetic physical examination results were not recorded (vs recorded) or when preanesthetic Hct [Hematocrit (Hct) Levels: the ratio of the volume of red cells to the volume of whole blood] was outside (vs within) the reference range. ... Underweight dogs had almost 15 times the odds of death as nonunderweight dogs. ... The only hematologic or physiologic variable identified as significant through multivariable modeling was Hct outside the reference range in dogs, which was associated with a 5.5-fold increase in the odds of death, compared with results for dogs that had values within the reference range. ... Conclusions and Clinical Relevance: Several factors were associated with anesthetic-related death in cats and dogs. This information may be useful for development of strategies to reduce anesthetic-related risks when possible and for education of pet owners about anesthetic risks.

Anesthetic Protocols for Brachycephalic Dogs. Tasha McNerney. Vet. Team Brief. March 2017. Quote: Brachycephalic dogs are becoming more popular as pets, which means veterinary nurses are more likely to be asked to anesthetize these dogs in practice. Brachycephalic dogs have a relatively broad, short skull, usually with the breadth at least 80% of the length.2 They often have anatomic abnormalities (eg, stenotic nares, elongated soft palate, hypoplastic trachea, laryngeal collapse, everted laryngeal saccules), known as brachycephalic syndrome, which can cause upper airway obstruction and mandate the use of special protocols when administering anesthesia.

Postanaesthetic pulmonary oedema in a dog following intravenous naloxone administration after upper airway surgery. Natalie Bruniges, Clara Rigotti.Vet. Rec. Case Rpts. June 2017; doi: 10.1136/vetreccr-2016-000410. Quote: A cavalier King Charles spaniel [8-years-old, 9.5 kg, BCS 6/9, intact male] was anaesthetised for upper airway surgery. ... The patient had been examined by a board-certified cardiologist two months previously and investigations had revealed a vertebral heart score (VHS) of 11 on thoracic radiography. A mild interstitial pattern was detected in both cranial lung lobes but there were no changes suggestive of cardiogenic pulmonary oedema or congestive heart failure. Echocardiography revealed preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) with subjective left atrial (LA) enlargement (maximum LA diameter 40.2 mm but 2D LA:Ao ratio 1.45, reference range 0.91–1.93) and mild pulmonary hypertension in both systole and diastole with pulmonary arterial pressure 48/18 mmHg, respectively. The patient was classified as having stage B1 heart disease not currently requiring treatment by a board-certified cardiologist. ... A constant rate infusion of fentanyl at 6 μg/kg/hour and top-up boluses (5 μg/kg in total) were used for intraoperative analgesia. Intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV) was instituted due to tachypnoea and inability to maintain normocapnia. Apnoea and severe hypercapnia developed after cessation of IPPV. IPPV was recommenced for 10 min to reduce hypercapnia, after which spontaneous ventilation returned. The patient had not awakened 45 minutes after isoflurane was turned off and 0.01 mg/kg naloxone was administered intravenously due to suspected fentanyl-induced narcosis. Following immediate arousal, the patient vomited and suddenly developed symptoms and radiographic changes consistent with pulmonary oedema. General anaesthesia was reinduced and 1 mg/kg furosemide was administered intravenously. IPPV was started with application of positive end expiratory pressure in an air/oxygen mixture for 60 minutes. Recovery was uneventful. This is the first report of a dog developing pulmonary oedema following intravenous naloxone. ... Development of naloxone-induced pulmonary oedema is a very rare complication in human beings and this is the first case report of its occurrence in a dog. As this dog had pre-existing MMVD with mild pulmonary hypertension, the authors speculate as to whether this increased the risk of developing subsequent pulmonary oedema, particularly as naloxone is believed to increase blood volume in pulmonary vasculature (Sarnoff and others 1953). Therefore, naloxone should be used more cautiously or even avoided in patients with underlying cardiac disease. In light of this case report and literature review, the authors suggest that opioid receptor antagonists should be diluted and titrated slowly to effect, particularly if administered intravenously.

The effect of heart disease on anesthetic complications during routine dental procedures in dogs. Jennifer E. Carter, Alison A. Motsinger-Reif, William V. Krug, Bruce W. Keene. J. Amer. Anim. Hosp. Assn. July 2017;53(4):206-213. Quote: Dental procedures are a common reason for general anesthesia, and there is widespread concern among veterinarians that heart disease increases the occurrence of anesthetic complications. Anxiety about anesthetizing dogs with heart disease is a common cause of referral to specialty centers. To begin to address the potential effect of heart disease on anesthetic complications in dogs undergoing anesthesia for routine dental procedures, we compared anesthetic complications in 100 dogs with heart disease severe enough to trigger referral to a specialty center (cases) to those found in 100 dogs without cardiac disease (controls) that underwent similar procedures at the same teaching hospital. Medical records were reviewed to evaluate the occurrence of anesthetic complications. No dogs died in either group, and no significant differences were found between the groups in any of the anesthetic complications evaluated, although dogs in the heart disease group were significantly older with higher American Society of Anesthesiologists scores. Midazolam and etomidate were used more frequently, and alpha-2 agonists used less frequently, in the heart disease group compared to controls. This study suggests dogs with heart disease, when anesthetized by trained personnel and carefully monitored during routine dental procedures, are not at significantly increased risk for anesthetic complications. (See Editor Annotation below.)

Editor Annotation to The effect of heart disease on anesthetic complications during routine dental procedures in dogs. Advances in Sm. Anim. Med. & Surg. November 2017;30(11):4-5. Quote: Veterinarians often worry about anesthetizing older dogs with heart disease for procedures such as dental extractions, cleaning, etc. The authors of this study examined, retrospectively, whether such dogs pose an increased risk, specifically of anesthetic complications. They found no associations of increased complications (defined as bradycardia, tachycardia, hypotension, hypoventilation, hypoxemia, hypothermia cardiac arrhythmias or cardiopulmonary arrest) during the anesthesia in dogs with heart disease compared to similar dogs without heart disease. This should be encouraging news for clinicians dealing with such dogs. However, several caveats and questions about the study exist. First, the authors included 66 dogs with confirmed mitral valve disease (and 22 with suspected mitral valve disease) but also included 12 dogs with other diseases, most of which cardiologists and anesthesiologists would not necessarily consider to be “at increased risk.” It would have been better to limit the study to just the 88 dogs with mitral valve disease. Second, the authors did not describe the severity of the heart disease in any detail – they simply stated that these dogs had “some evidence of cardiac enlargement, with or without a history of congestive heart failure” (which was being effectively controlled with medications). Therefore, it is very difficult to determine just how severely affected these dogs were. It is possible that many of them had mild disease – a situation that would not be of anesthetic concern. The ASA ratings for these dogs were Grade 2 (mild risk) or Grade 3 (moderate risk) for almost all dogs, suggesting that most dogs were not severely affected. Third, the authors observed that anesthesiologists used different drug protocols in the dogs with heart disease, with a much higher use of midazolam and etomidate than in the control dogs (matched dogs without heart disease). Therefore, the dogs in each group were not treated equally. Fourth, the authors did not consider post-anesthetic complications. Studies have shown that most feline deaths attributed to anesthesia occur in the hours after anesthesia, not during. It is possible that dogs with mitral valve disease might have developed congestive heart failure shortly after discharge, as a result of the stress of the procedure, or fluid overload. Finally, these results were obtained from dogs anesthetized by trained anesthesiologists in a referral institution (veterinary teaching hospital). Therefore, extrapolating these findings to general practice is, at best, a long stretch. Whether practitioners with minimal training in anesthesia and no dedicated anesthetic staff monitoring the patients would achieve the same outcomes cannot be determined. Having said that, clinicians should consider anesthetizing older dogs with mitral valve disease if (i) the mitral valve disease is not too severe; (ii) the condition requiring the anesthesia warrants immediate intervention; and (iii) the clinician is comfortable with the anesthetic and fluid protocols that reduce risk of anesthetic complications. All these factors should be considered and discussed with clients when deciding whether or not an anesthetic procedure is warranted and whether or not the patient should be referred to a specialty institution for more comprehensive assessment and monitoring.

Influence of sevoflurane or propofol anaesthesia on oxidative stress parameters in dogs with early-stage myxomatous mitral valve degeneration. A preliminary study. Katerina Tomsic, Alenka Nemec Svete, Nemec Ana, Domanjko Petrič Aleksandra, Tomaz Vovk, Seliškar Alenka. Acta Veterinaria-Beograd. March 2018;68(1):32-42. Quote: The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of total intravenous anaesthesia with propofol and anaesthesia induced with propofol and maintained with sevoflurane on oxidative stress parameters in dogs with early-stage myxomatous mitral valve degeneration (MMVD) [Stage B1 or B2]. Sixteen client-owned dogs with early stage MMVD that required periodontal treatment were included in the study. [Breeds not identified.] After induction with propofol, anaesthesia was maintained with propofol (group P) or sevoflurane (group PS). Blood samples for determination of vitamin E, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase and malondialdehyde were collected before premedication, 5 and 60 minutes and 6 hours after induction to anaesthesia. There were no significant differences between groups in any of the oxidative stress parameters at each sampling time. Compared to basal values, vitamin E concentration decreased significantly during anaesthesia in both groups and glutathione peroxidase activity increased 60 minutes after induction to anaesthesia in PS group. Anaesthesia with propofol or with propofol and sevoflurane did not have any significant impact on oxidative stress parameters in dogs with early stage MMVD. In terms of oxidative stress, both protocols may be equally safely used in dogs with early stage MMVD.

Dose-dependent effects of isoflurane and dobutamine on cardiovascular function in dogs with experimental mitral regurgitation. Seijirow Goya, Tomoki Wada, Kazumi Shimada, Daiki Hirao, Ryou Tanaka. Vet. Anaesthesia & Analgesia. April 2018. DOI:10.1016/j.vaa.2018.03.010. Quote: Objective: To investigate the dose-dependent effects of isoflurane and dobutamine on haemodynamics in dogs with experimentally induced mitral valve insufficiency (MI). Study design: Experimental, dose-response study. Animals: A group of six healthy Beagle dogs. Methods: Dogs with surgically induced MI were anaesthetized once. First, anaesthesia was maintained at an end-tidal isoflurane concentration (Fe´Iso) 1.0% (ISO1.0) for 20 minutes. Then, dobutamine was infused successively at 2, 4, 8, and 12 μg kg−1 minute−1 (DOB2–12) for 10 minutes at each dose rate. Measurements were recorded at each stage. Dobutamine was discontinued and Fe´Iso was increased to 1.5% (ISO1.5) for 20 minutes. Dobutamine was administered similarly to ISO1.0 and cardiovascular variables were recorded. The same sequence was repeated for Fe´Iso 2.0% (ISO2.0). Aortic pressure (AoP) and left atrial pressure (LAP) were recorded by radiotelemetry. The combination method of the pressure-volume loop analysis and transoesophageal echocardiography was used to measure cardiovascular variables: end-systolic elastance (Ees), effective arterial elastance (Ea), Ea/Ees, forward stroke volume (FSV), heart rate (HR), and cardiac output (CO). Results: High isoflurane concentration resulted in reduced Ees and increased Ea/Ees, which indicated low arterial pressure. High dose dobutamine administration resulted in increased Ees and FSV at all isoflurane concentrations. In ISO1.5 and ISO2.0, HR was lower at DOB4 than BL but increased at DOB12 compared with DOB4. CO increased at ≥DOB 8 compared with BL. In ISO1.5 and ISO2.0, systolic and mean AoP increased at ≥DOB4 and ≥DOB8, respectively. LAP did not change under all conditions. Conclusions and clinical relevance: The dose-dependent hypotensive effect of isoflurane in MI dogs was mainly derived from the decrease in contractility. Dobutamine increased AoP without increasing the LAP by increasing the contractility attenuated by isoflurane. The findings of this study may improve the cardiovascular management of dogs with MI undergoing general anaesthesia with isoflurane.

Risk of anesthesia-related complications in brachycephalic dogs. Michaela Gruenheid, Turi K. Aarnes, Mary A. McLoughlin, Elaine M. Simpson, Dimitria A. Mathys, Dixie F. Mollenkopf, Thomas E. Wittum. JAVMA. August 2018;253(3):301-306. Quote: Objective: To determine whether brachycephalic dogs were at greater risk of anesthesia-related complications than nonbrachycephalic dogs and identify other risk factors for such complications. Design: Retrospective cohort study. Animals: 223 client-owned brachycephalic dogs [none were cavalier King Charles spaniels] undergoing general anesthesia for routine surgery or diagnostic imaging during 2012 and 223 nonbrachycephalic client-owned dogs matched by surgical procedure and other characteristics. Procedures: Data were obtained from the medical records regarding dog signalment, clinical signs, anesthetic variables, surgery characteristics, and complications noted during or following anesthesia (prior to discharge from the hospital). Risk of complications was compared between brachycephalic and nonbrachycephalic dogs, controlling for other factors. Results: Perianesthetic (intra-anesthetic and postanesthetic) complications were recorded for 49.1% (n = 219) of all 446 dogs (49.8% [111/223] of brachycephalic and 48.4% [108/223] of nonbrachycephalic dogs), and postanesthetic complications were recorded for 8.7% (39/446; 13.9% [31/223] of brachycephalic and 3.6% [8/223] of nonbrachycephalic dogs). Factors associated with a higher perianesthetic complication rate included brachycephalic status and longer (vs shorter) duration of anesthesia; the risk of perianesthetic complications decreased with increasing body weight and with orthopedic or radiologic procedures (vs soft tissue procedures). Factors associated with a higher postanesthetic complication rate included brachycephalic status, increasing American Society of Anesthesiologists status, use of ketamine plus a benzodiazepine (vs propofol with or without lidocaine) for anesthetic induction, and invasive (vs noninvasive) procedures. Conclusions & Clinical Relevance: Controlling for other factors, brachycephalic dogs undergoing routine surgery or imaging were at higher risk of peri- and postanesthetic complications than nonbrachycephalic dogs. Careful monitoring is recommended for brachycephalic dogs in the perianesthetic period.

Anaesthesia of brachycephalic dogs. F. Downing, S. Gibson. J.S.A.P. October 2018;doi: 10.1111/jsap.12948. Quote: Brachycephalic breeds of dog have grown in popularity in the UK and so form an increasing proportion of cases requiring anaesthesia. These breeds are predisposed to several conditions, notably brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome and gastro-oesophageal reflux, that have important implications for anaesthetic management and carry high risk for complications. This review incorporates peer-reviewed veterinary literature with clinical experience in a discussion on perioperative management of brachycephalic dogs. We focus on preoperative identification of common concurrent conditions, practical strategies for reducing anaesthetic risk and improving postoperative management. Comparisons of brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome with the human condition of obstructive sleep apnoea are included where appropriate.

Effect of methadone and acepromazine premedication on tear production in dogs. Hayley A Volk, Ellie West, Rose Non Linn-Pearl, Georgina V Fricker, Ambra Panti, David J Gould. Vet. Rec. open. December 2018;5:e000298. Quote: Objectives: To evaluate the combined effect of intramuscular acepromazine and methadone on tear production in dogs undergoing general anaesthesia for elective, non-ocular procedures. Design: Prospective, non-randomised, pre-post treatment study. Setting: Patients were recruited from a referral practice in the UK. Methods: Thirty client-owned dogs [including two cavalier King Charles spaniels] were enrolled in this study and received a combined intramuscular premedication of methadone (0.3 mg/kg) and acepromazine (0.02 mg/kg) before general anaesthesia for elective, non-ocular procedures. Full ophthalmic examination was performed and tear production was quantified using the Schirmer tear test-1 (STT-1). On the day of general anaesthesia, an STT-1 was performed before (STT-1a) and after (STT-1b) intramuscular premedication with methadone/acepromazine. Results: Using a general linear model, a significant effect on STT-1 results was found for premedication with methadone/acepromazine (P=0.013), but not eye laterality (P=0.527). Following premedication, there was a significant reduction observed in the mean STT-1 readings of left and right eyes between STT-1a (20.4±2.8 mm/min) and STT-1b (16.9±4.1 mm/min; P<0.001). Significantly more dogs had an STT-1 reading less than 15 mm/min in one or both eyes after premedication (30 per cent; 9/30 dogs) [including one of the CKCSs] compared with before premedication (6.7 per cent; 2/30 dogs; P=0.042). Conclusions: An intramuscular premedication of methadone and acepromazine results in a decrease in tear production in dogs before elective general anaesthesia. This may contribute to the risk of ocular morbidities, such as corneal ulceration, particularly in patients with lower baseline tear production.

A comparison of propofol and alfaxalone in a continuous rate infusion in dogs with mitral valve insufficiency. Capik I., Polkowska I., Lukac B. Veterinarni Medicina. August 2019;64(8):335-341. Quote: The aim of this study was to compare alfaxalone and propofol in balanced anaesthesia using midazolam 0.5 mg/kg, xylazine 0.125 mg/kg, butorphanol 0.2 mg/kg intravenously as premedication and the ultrashort acting anaesthetics alfaxalone or propofol for inducing and maintaining in dogs with medically stabilised mitral valve regurgitation. Seven client-owned dogs with a second stage cardiac insufficiency were used in this study. All the dogs suffered from class II cardiac insufficiency according to the classification by the International Small Animal Cardiac Health Council (ISACH). All the dogs were treated with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (enalapril) and diuretics (furosemide), which eliminated the clinical signs of mitral valve regurgitation in all the dogs included in the study. This was a prospective controlled clinical study, 12 months in duration, when the dogs included in the study underwent regular dental prophylaxis. The dogs were monitored electrocardiographically throughout the anaesthesia for the presence of arrhythmias, % oxygen saturation of haemoglobin (%SpO2) measured by pulse oximetry, heart rate, respiratory rate and body temperature. The dogs underwent two anaesthesia procedures with an interval of one year due to the prophylaxis of periodontitis, with the first anaesthesia maintained by propofol and second one by alfaxalone. The respiratory rate was mostly significantly higher in the individuals undergoing alfaxalone anaesthesia (P < 0.05), but neither the slower respiratory frequency in the propofol anaesthesia had any negative impact on the % oxygen saturation of the haemoglobin (%SpO2). The heart frequency was significantly higher in the alfaxalone group (P < 0.005). The arterial blood pressures were comparable, but, on the contrary, the two dogs from propofol group had significantly higher blood pressure. The cardiovascular values in both types of anaesthesia had a tendency to progressively decrease within the physiological range. The level of the analgesia was significantly higher in the case of the propofol anaesthesia (P < 0.01) and the recovery period was also significantly shorter (P < 0.005). It can be concluded that the investigated ultra short acting anaesthetics used in balanced anaesthesia containing subanaesthetic doses of xylazine can be used over one hour of surgical procedures in dogs stabilised for mitral valve regurgitation without a significantly increased risk from the anaesthesia.

Anaesthetic management and complications of transvascular patent ductus arteriosus occlusion in dogs. Carmelo Parisi, Victoria Phillips, Jacques Ferreira, Chris Linney, Alastair Mair. Vet. Anaesth. & Analgesia. April 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.vaa.2020.01.009. Quote: Objective: To retrospectively analyse the anaesthetic management, complications and haemodynamic changes in a cohort of dogs undergoing transvascular patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) occlusion in a tertiary referral centre (January 2017 to August 2018). Study design: Retrospective study. Animals: A total of 49 client owned dogs [5 (10.2%) Cavalier King Charles Spaniels]. Methods: Anaesthetic records of dogs with PDA, which underwent transvascular occlusion of the ductus were reviewed. Anaesthetic complications evaluated included tachycardia [heart rate (HR) > 160 beats minute-1], bradycardia (HR < 50 beats minute-1), hypertension [systolic arterial pressure (SAP) > 150 mmHg], hypotension [mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 60 mmHg], hypothermia (<37°C) and the presence of arrhythmias. Cardiovascular variables [HR and invasive SAP, MAP and diastolic arterial pressure (DAP)] at the time of occlusion device deployment (time 0) were compared with variables at 5 and 10 minutes after deployment. Descriptive statistics, Shapiro-Wilk test and repeated measures ANOVA followed by a Dunnett’s post-hoc test were used to analyse the data (p < 0.05). Results: Crossbreed dogs were the most commonly represented followed by the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. The median age was 8 (2 - 108) months and female dogs were over-represented (65.3%). The most common American Society of Anesthesiologists was 3. Mean duration of anaesthesia was 96 ± 26 minutes and mean surgery time 58 ± 21 minutes. Acepromazine with methadone was the most commonly used premedication combination (77.6%). Propofol was the most common induction agent (73.5%). General anaesthesia was maintained with isoflurane in oxygen in all dogs. Complications included hypotension (63%), hypothermia (34%), bradycardia (28%), arrhythmias (16%), hypertension (16%) and haemorrhage (2%). MAP and DAP increased significantly 10 minutes after device deployment compared with time 0. Conclusions and clinical relevance: Hypotension was the most common complication reported in dogs undergoing transvascular PDA occlusion. No major adverse events were documented.

Effect of Medetomidine, Dexmedetomidine, and Their Reversal with Atipamezole on the Nociceptive Withdrawal Reflex in Beagles. Joëlle Siegenthaler, Tekla Pleyers, Mathieu Raillard, Claudia Spadavecchia, Olivier Louis Levionnois. Animals. July 2020; doi: 10.3390/ani10071240. Quote: Medetomidine, an alpha-2 agonist routinely used to provide sedation and pain relief in dogs, is a mixture of dexmedetomidine and levomedetomidine in equal proportions. Dexmedetomidine, considered to be the only active component in the mixture, is also marketed alone. Sedation caused by both formulations can be reversed using atipamezole, which shortens recovery. Dexmedetomidine provides analgesic effects similar to medetomidine, but it remains unclear at which dose and whether the analgesic effects of medetomidine or dexmedetomidine disappear once atipamezole is injected. The present trial aimed at elucidating these uncertainties using the nociceptive withdrawal reflex model. This model allows for quantification of analgesia by measuring specific activity from muscles involved in limb withdrawal in response to mild electrical stimulation. In eight beagles, the model was applied to compare the extent of pain relief provided by medetomidine and dexmedetomidine and to investigate whether complete reversal occurs after the administration of atipamezole. No difference in analgesic efficacy was identified between the two formulations. Both sedation and pain relief terminated rapidly when atipamezole was administered. These findings indicate that medetomidine and dexmedetomidine provide comparable levels of pain relief and that additional analgesics may be necessary when atipamezole is administered to dogs experiencing pain.

Anesthesia Case of the Month. Dario A. Floriano, Alexandra V. Crooks, Marc S. Kraus, Ciara A. Barr. JAVMA. August 2020;257(4):379-382. Quote: A 9-month-old 6.2-kg (13.6-lb) sexually intact male Cavalier King Charles Spaniel with pulmonary valve stenosis was referred for cardiac consultation regarding treatment with balloon valvuloplasty. The owners reported that the dog had no clinical signs of heart disease but a history of a grade 5/6 heart murmur since birth. ... With exclusion of other causes, we suspected a right-to-left cardiac shunt as the main underlying cause of hypoxemia in the dog of the present report. ... A right-to-left shunt is a condition in which blood from the right side of the heart enters the left side without passing through the lungs for gas exchange. ... Therefore, agitated-saline echocardiography was performed, and findings confirmed the presence of a right-to-left atrial-level shunt. ... Findings in the dog of the present report provided a reminder that patients could have multiple congenital cardiac defects. We recommend that before patients with congenital cardiac defects undergo general anesthesia, they first undergo full cardiac evaluation, including agitated-saline echocardiography to evaluate for a preexisting atrial-level shunt, and have their Spo2 and PCV evaluated so that potential shunt-related complications (eg, hypoxemia) may be more readily identified and addressed.